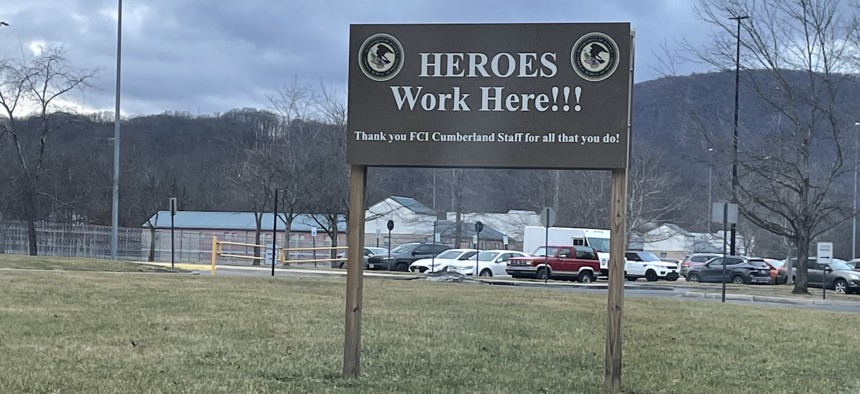

This sign greets visitors on the drive leading up to the federal correctional institution facility in Cumberland, Md. Staffing shortages have added to the stress of correctional officers across the federal prisons system, including those here. The bureau’s new director, Colette Peters, is trying to address this and other longstanding issues at the agency. COURTNEY BUBLÉ/Government Executive

'It's Not Just Club Fed': A Day Inside One Facility in the Strained Federal Prisons System

A visit to a Bureau of Prisons facility in Maryland showed some of the challenges the agency is facing as a new director tackles reforms.

The Federal Bureau of Prisons has 122 facilities, houses about 158,259 inmates and employs about 34,400 people. The agency’s new director has said she would like to prioritize reforms that would alleviate some of the stresses on the system, including chronic understaffing. Recently, GovExec toured the federal correctional institution facility in Cumberland, Md., and got a glimpse into its inner workings and what its correctional officers face on a daily basis.

There is a college campus-like feel to this federal prison. Outdoor walkways connect buildings and there are lots of trees and views of the mountains in the distance. But while it may look bucolic, the correctional officers who spend long workdays here say there are a lot of misconceptions about what their job is like.

“There’s a lot of celebrities that go to prison. A lot of times what you hear about is their living conditions, the work assignments and stuff like that, but there's more to it. People come here and spend the majority of their lives here,” said Taven Rohrbaugh, a correctional officer at the medium security prison. He joined his brother, Kasion, a fellow correctional officer, at the institution in May 2020.

“Just the stress of the officer, having to be here and responsible for what could happen, a lot of people don’t realize how dangerous it could be,” he continued. “You could go here and have nothing happen for months at a time, but just knowing in the back of your head at any point in time, things can change.”

In recent years staffing shortages have added to the stress of correctional officers across the federal prisons system, which the COVID-19 pandemic only exacerbated, and that is something the bureau’s new director, Colette Peters, is trying to address in addition to changing the agency’s reputation and improving employee wellness. “They're exhausted, they're overworked,” she said in an interview with Government Executive in October, about two months after she was sworn in. “And so, it really is one of the top priorities for the executive team in the bureau.”

A Cat and Mouse Game

While some correctional officer responsibilities might seem repetitive and mundane, such as counting and tracking pool balls in the recreation room or tools in the woodshop area, they serve a larger purpose: preventing misuse or abuse of items by inmates. Corners can’t be cut. Incoming and outgoing mail has to be screened using a special technology while employees wear proper gear. This is important not only for everyone’s safety, but because mail is a lifeline for inmates to stay in touch with loved ones.

In the housing unit, the correctional officer on duty has to take census counts; conduct bar taps; constantly listen to the radio; and be aware of any fights, disturbances or other activity going on as well as conduct at least five cell or area searches per shift. During searches, officers must be wary of anything that could stab them, so they use hand tools to touch prisoners’ belongings and a mirror. It can be a “cat and mouse” game to find illicit items, as contraband can be hidden in instant ramen noodle packages or a soda bottle.

Officers at this complex, which houses about 1,042 inmates, aren’t just trying to root out bad behavior; they are also helping to rehabilitate the prisoners. At lunch – on this day it was a fried chicken patty or a substitute vegetarian option, with a bun, lettuce, tomato, rice, beans and vanilla cake with chocolate frosting – executive staff make themselves available to answer questions and serve as a resource, such as connecting inmates with the psychiatrist's office. Since movement is controlled, staff ensure inmates get to their scheduled activities and appointments throughout the day, whether it be a medical check-up, a work shift or educational classes.

.jpeg)

And while dogs and summer camps might not come to mind when you think of prisons, staff help facilitate activities with both. Since 2005, the adjacent minimum security satellite camp has had a partnership with a local nonprofit, Fidos for Freedom, that allows inmates to live with and train dogs for a year. Once training ends the dogs are returned to the nonprofit and placed in homes in the Washington, D.C., area. Also, for at least 20 years the institution has run a summer camp in partnership with the Hope House of Washington, D.C., for children whose fathers are incarcerated. The children stay at a camp nearby for a week and get to do activities with their fathers.

FCI Cumberland has been called “Club Fed,” as many high-profile criminals have served time there: Bernard Kerik, the former commissioner of the New York Police Department nominated by President George W. Bush to be secretary of the Homeland Security Department, who was convicted of tax fraud and lying to officials (he was later pardoned by President Trump); Jack Abramoff, who pleaded guilty to criminal conspiracy and failing to register as a lobbyist in the Native American lobbying scandal; Webster “Webb” Hubbell, a former U.S. attorney general who was convicted of wire fraud and one count of failing to disclose a conflict of interest for his part in the Clintons’ Whitewater controversy; and John Beale, an Environmental Protection Agency official who faked CIA duty. Jeffrey MacDonald, a former army doctor who murdered his pregnant wife and two daughters, is also there serving a life sentence.

But “it's not just ‘Club Fed,’” said Bill McMahan, president of the local BOP union, and Cumberland has struggled with the effects of a reduced workforce, as has the rest of BOP.

More Correctional Officers, Please

The inspector general for the Justice Department, which houses the prisons bureau, has consistently flagged “managing the federal prison system as one of the most significant and important management challenges facing the department.” There have been various reports from the media, Congress, the Justice Department and the Justice inspector general, about alleged sexual misconduct by and against BOP employees. There has been a years-long staffing shortage, which the union has repeatedly decried due to the strain it puts on staff. BOP has been forced to rely more on overtime and augmentation, which is when teachers, cooks, nurses or other employees fill in as correctional officers. BOP employees are trained as correctional officers first, which isn’t always the case in lower levels.

At Cumberland “it may not be as bad here as it is in some other places, but we definitely need to hire more officers,” Kasion Rohrbaugh said.

According to data from BOP there are currently just short of 100 correctional officers at Cumberland between the medium security facility and adjacent camp. There were 119 in 2015 and 110 in 2002.

The agency told the union local president that the optimal number of officers would be 107, McMahan said. But going by the 2016 baseline, as required by congressional appropriations, there should be 120, he added.

Methods for assessing staffing levels have been a challenge for the agency, as the Government Accountability Office reported in February 2021, and the bureau is working to address its recommendations. Also, the inmate-to-staff ratio can vary by shift, as the agency has told Congress in reports.

For a while now union officials have been disputing the baseline the agency uses to access its staffing level.

“The BOP's staffing level is dependent on the appropriated funds received for this purpose,” agency officials said. “Increasing authorized staffing levels needs to be addressed through the congressional budget request and appropriation process.”

Safety Concerns

“As far as the facility here itself, it’s a great place… when you think of prison, there’s not a whole lot of violence here,” said Kevin Smith, a 25-year correctional officer who mainly works at the camp. But with less staff the challenge “is No. 1, probably safety of the officers.”

During emergencies “if I hit my body alarm and I need help because of the situation…those staff that were working as counselors, case managers, wherever, they're actually filling in for the officer,” Smith said. “So it’s really dangerous to run with low numbers, not having your staffing. And then what happens is, if you’re an officer, you may have to work a double, 16-hour shift, you’re tired, and then [if] you’re in the same kind of emergency situation you just don’t have the back up and you don’t have the staffing numbers. And the frustration for an officer, just the officer’s point of view, is am I going to get stuck here 16 hours? And then it just wears on you.” When the employees who don’t usually work as correctional officers, have to fill in as such, “their work piles up…and for the morale part of it, it’s not good.”

A retirement wave is also sweeping the bureau. Shane Fausey, national president of the Council of Prison Locals, told lawmakers last fall that in December 2021 the bureau had both the most retirements in a month and most retirements in a year. According to BOP data, there were 21 retirements among Cumberland staff in 2022, followed by 18 in 2021. In 2020 and 2019 there were seven and nine retirements, respectively.

.jpeg)

“Recruitment-wise, we are in an area that has state prisons, county jails and other law enforcement agencies, so locally we compete with their salaries,” said Billy Joe Wrights, who recently celebrated his 23-year work anniversary at Cumberland..

Kasion Rohrbaugh pointed out that the Pay Our Correctional Officers Fairly Act introduced in the House in November 2021 would increase locality pay for BOP employees by treating prisons located in the “Rest of U.S.” category as if they were actually located in the nearest locality pay area approved by the president’s pay agent. After last year’s recommendations from the Federal Salary Council and decisions by the President's Pay Agent, Cumberland may see an increase in locality pay, but the earliest that will happen is January 2024.

Staffing and employee wellbeing are top priorities for Peters who took over the agency in August. While she has acknowledged there needs to be other reforms, such as ensuring employees who engage in wrongdoing are held accountable and ensuring headquarters staff is held accountable for carrying out watchdog recommendations, Peters told Government Executive back in the fall that “99.9% of our employees come to work every day doing the right thing and when we have individuals who make poor choices or make egregious choices that are criminal, we are all as embarrassed and outraged as the general public.”

“Heroes Work Here”

“At FCI Cumberland you have people that want to do the job, every day, all day long,” McMahan said.

This includes Wrights, who has been working as a drug treatment specialist for the last seven years. “I've seen over the years, as a staff member, you got to make sure that you get your sleep, exercise, eat healthy and you maintain good relationships at work because it is a prison,” Wrights said.

He got his doctorate degree in 2019 because he wanted to further his education “and be able to help people better, and [the Residential Drug Abuse Program has] been a great opportunity for me to do that,” he explained. In his more than two decades at the facility, Wrights has seen gradual changes with an increased focus on preventing reentry of prisoners once they are released. Wrights said he makes his days enjoyable by talking to staff and getting to know inmates. When he initially started working with BOP, his main focus was pay, benefits and retirement; purpose has kept him here.

But Wrights has to compartmentalize to maintain balance.

“You keep work at work and home at home a lot of times,” he said, as it's often difficult to go home and tell your family about what happens on a daily basis. As for the general public, he said he likes when tours come in because they get to see “trees, and inmates dressing properly, inmates involved in programming, the safety of it, the cleanliness of the institution and that it’s not as bad as TV portrays prisons to be.”

Kasion Rohrbaugh, who has been at Cumberland since 2015, and his brother, Taven, don’t talk much with friends and family about the job either, but they live together and often serve as sounding boards for one another about things they experience at work. Kasion encouraged his brother to come work at Cumberland with him because of the pay, the environment and his colleagues, whom he describes as “really really trained professionals.”

Kasion said there is a daily stress being in a correctional environment because “we’re seeing the other part of life where these inmates they’re confined to a prison, to the cell, especially in the special housing unit and you just see a lot of depressing things.” Special housing units are for inmates to be separated from the general inmate population, such as for disciplinary reasons or their own protection.

He and Taven mainly work in the special housing unit, and both emphasized the need for teamwork and employees looking out for each other. Taven stated there is job security, but for him, it’s “not just a job, like I actually have a career here.”

A Bureau Family

Despite the portrayal that the federal prison system is troubled and broken, according to Fausey, of the Council of Prison Locals, “when you look specifically at the rate of misconduct, it’s so low that when something does happen, it’s kind of shocking,” he said. Also, the “Hollywood version of prison” is inaccurate.

McMahan said he will believe the new director’s reforms when he sees them. He also noted that unlike at other institutions, in the federal ones, “everybody’s a correctional worker first,” so people help each other out in times of crisis.

It’s like a “bureau family,” he said. “We’re all in there, we’re all in the same team. Even though we might not like each other on the street. In there, we’re on the same team.”