VA Instructs Coronavirus-Exposed Staff to Continue Working, Places Those Who Don’t in AWOL Status

"This is the absolute worst-case scenario of anything I have ever experienced in my nursing career," according to one registered nurse.

Employees at the Veterans Affairs Department are feeling pressured to return to work even after they've been exposed to the novel coronavirus—a new VA policy requires them to continue showing up, and threatens discipline along with the possibility of losing pay for those who stay home.

The situation is creating a stressful environment in which VA workers worry their colleagues may be hiding symptoms while they have insufficient equipment to protect themselves and others from spreading the virus. Government Executive spoke to employees at more than a half-dozen facilities, all of whom said management was providing inconsistent guidance and creating unsafe working conditions.

To date, more than 5,000 patients and 1,600 staff at VA facilities have tested positive for COVID-19; more than 300 patients and more than a dozen staff have died from the disease. Until recently at some facilities, staff told Government Executive, some administrative staff were not even allowed to wear masks, either because there weren't enough to go around and they were being reserved for medical personnel with more sustained patient contact, or because supervisors were worried about alarming patients and visitors.

At some facilities, VA officials have instituted policies under which employees who worked with COVID-19 positive patients before their status was known—and therefore were not wearing the proper equipment—should continue to work until they develop symptoms, after which they could be tested for the virus. In some cases, those employees included nurses and doctors who subsequently tested positive for the virus but returned after seven days when their symptoms were no longer evident, employees said. One memorandum sent by a top official at a medical center in Indianapolis said VA facilities should consider enabling employees “who have had an exposure to a COVID-19 patient to continue to work after options to improve staffing have been exhausted.”

Christina Noel, a VA spokeswoman, said the department was following Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidance, as well as its own protocols, in allowing employees to continue working after exposure to the virus. Contradicting reports from employees, she said staff who test positive can only return to work after being asymptomatic for 10 days.

Those who take time off to self-isolate after a potential exposure without experiencing symptoms risk being labeled “absent without leave,” according to employees at multiple facilities, a status that cuts off paychecks and negatively impacts future pay, promotion opportunities and performance metrics. Employees may take sick leave if they have it available, but supervisors have discretion to reject such requests.

Those with a positive test or a known exposure but who are asymptomatic are told to return to work and wear a mask. While VA has said it has sufficient personal protective equipment for its employees, the Veterans Health Administration sent out a departmentwide memo last week notifying employees it had implemented “crisis capacity strategies for mask and N95 respirator conservation until supply chains are optimized.” At VA facilities across the country, employees working in areas thought to be less at risk for COVID-19 exposure, including nursing homes, spinal cord injury facilities and mental health wards, are receiving only one face mask per week. One employee working in a high-risk unit said she and her colleagues had to keep their masks “until they are falling from our faces.”

"Care should be taken to not touch the outer surface of the mask when removing the mask from a paper storage bag when used,” the memo read.

The more sophisticated N95 masks that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has deemed most effective in protecting workers from the virus are rarely seen anywhere in a VA medical center or clinic, according to every employee with whom Government Executive spoke. Only those in intensive care units or emergency rooms receive them, the employees said. As recently as early March, supervisors at multiple VA facilities were instructing employees to remove masks as they were causing unnecessary alarm with patients. Employees at three facilities said workers were not wearing masks until last week.

One nurse in Indianapolis said her surgical mask was “saturated” with sweat during her 12-hour shift, but she was denied a new one.

“How infected is a wet mask?” she said. “There’s no barrier when it’s soaking wet.”

Noel said VA “has not encountered any PPE shortages that have negatively impacted patient care or employee safety.” She added on Thursday the department shifted from “crisis” capacity posture for PPE use to “contingency.”

Reporting Staff AWOL

At a clinic in the Las Vegas area, an advanced medical support assistant whose job involves the administrative aspects of coordinating VA patient care, was directed by her personal physician to be tested for COVID-19 in March after she developed a sore throat and a fever of 102 degrees. She told her boss she would stay home until she received her test results and forwarded the doctor’s note instructing her to do so. At that time, it was taking up to two weeks to receive test results. Without being told, she was placed on AWOL status for nine of the 10 work days she missed. The employee, a cancer survivor with a weakened respiratory system, had already exhausted all of her sick leave.

Before she returned to work after testing negative for the virus, her doctor gave her an N95 mask from the doctor's own supply due to concerns about her vulnerability as a cancer survivor, but her supervisor at VA prohibited her from wearing any mask at all. Later, VA provided her one standard mask per week. She is now home again with pneumonia on unpaid status.

The situation is straining her finances “beyond words,” she said. “It stresses me. I’m trying my best not to get that way because it’s exacerbating my illness. I’m not healing.”

Myoshi North is also an advanced medical support assistant, in Biloxi, Mississippi. Last month, she was assigned to screen patients coming into the medical center for coronavirus symptoms. Her requests for PPE were ignored, she said. North subsequently contracted the virus and upon receiving a positive test was forced to quarantine for 14 days.

But when she received her next paycheck, North learned she had been placed in an unpaid status during part of her absence. North said her supervisor explained that she wasn't paid because she wasn't teleworking during that time—despite the fact that North has not been trained and lacks the equipment necessary to perform her job remotely, she said.

“Now, not only do I have to worry about recovering from the COVID-19 virus, I have to struggle with my financial obligations as well,” North said.

VA headquarters has given its facilities broad discretion in how to charge leave to its employees, according to multiple individuals familiar with the plan, leading to inconsistent policies around the country. A nurse in Iowa who tested positive for the virus, for example, told Government Executive she was provided advanced sick leave to cover her time off. She now has negative-88 hours of leave accrued.

Richard Stone, acting head of the VHA, issued a memo last month authorizing facilities to provide administrative leave to anyone forced to quarantine or otherwise unable to come into work due to the pandemic. Each facility has its own discretion to implement that order, however, anecdotal evidence suggests it is seldom being used. Noel said VA is encouraging employees to use sick leave if they are ill, but did not address questions about employees in AWOL status.

Another Las Vegas employee took her twins to the hospital after one developed a fever. A doctor there suspected the 5-year-old had COVID-19, and, upon learning the mother worked at a VA hospital, told her not to return to work. The employee provided her supervisor with a note from the doctor saying she was “instructed to stay home.” Her supervisor responded that she would be placed in AWOL status, noting in an email it was "not ideal" but "it will not be avoidable."

The employee returned to her clinic, but within days began to feel sick. She went to work anyway, not wanting to risk more unpaid time off. A facility employee checked her temperature before she entered one morning and it registered as 102 degrees. She was directed to a tent outside the facility, where a doctor confirmed the temperature reading and told her she could not work that day. He called her supervisor to relay the news, but the supervisor told her to go to another area for employee medical treatment.

“Take some Tylenol and you’ll be fine,” the employee was told. “Just go back to work.”

So she did.

'This Clinic Is a Petri Dish'

Conditions for those still reporting to work are just as difficult. An Alabama-based employee noted that five employees at a VA clinic in Anniston had tested positive for COVID-19, leading the department to require tests for all of its roughly 25 workers there. VA kept the clinic open and told employees to continue reporting to work.

“This clinic is a petri dish,” the employee said. Staff there is “panicked,” she said, because one of those who tested positive was a supervisor who “has come in contact with everyone in the clinic.” It is also an outlier, as VA employees around the country said their facility was not authorizing tests for any employees who were asymptomatic.

The Indianapolis nurse who said she was denied a replacement for her sweat-saturated surgical mask has cycled in and out of her medical center’s COVID-19 unit. When with coronavirus patients, no one else is allowed into the room. She brings in a phone so doctors and specialists can speak to the patients. The rooms are not cleaned until a patient leaves, meaning the nurses, rather than janitorial staff, have to clean feces and urine that wind up on the floor. They make do with wash cloths, but do not have sanitizing products available, the nurse said.

Nurses are supposed to change their scrubs before going into the COVID unit, she said, but they do not currently have enough to carry out that policy. Employees place their personal items in a bag and then place the bag on a floor in the hallway. They have to change in the break rooms, where they leave their clothes, including their shoes, because they do not have sufficient foot coverings. There are “shoes and clothes everywhere” when employees take a break to eat, she said.

The nurse said when the virus first began to spread, employees were told to quarantine for 14 days after they were exposed to it. That was reduced to seven days, then three, and now they must continue working unless they develop symptoms.

“And that’s if you’re lucky enough to know you’ve been exposed,” she said, noting the facility has stopped notifying employees about their exposure to the virus.

Multiple nurses in Indianapolis said the COVID units are overwhelmed, meaning patients are sent back to regular parts of the hospital at the first sign of a fever breaking, before they have been retested for the virus to determine if they are still positive. On several occasions, the fever returned within 48 hours, exposing more individuals to the virus before the patient was returned to the COVID unit.

“Patients are coughing in your face,” one nurse said of the veterans who were cleared to return to a non-COVID ward. Inevitably, she said, their fevers develop again, and they are sent back down.

“I know I’ve been exposed four times,” said the first nurse. She explained the facility briefly screened nurses upon entering each day, but then stopped when the facility began running out of disposable thermometers. After reporting one exposure to her supervisors, a facility official told the nurse to take her temperature on the same thermometer being used on a patient.

Another nurse at the facility who is pregnant had saved up her paid time off to take maternity leave. But after she tested positive for the virus she used all of her accrued leave while home recovering. She recently was retested but continues to test positive for COVID-19, forcing her to remain at home on leave without pay. At this point, she no longer has any leave available for maternity leave. To avoid a similar fate, nurses at several facilities said they knew of colleagues who are hiding their symptoms to avoid being sent home.

“Right now we call it a cesspool,” one said. “You just don’t feel safe. You don’t feel like it’s clean.”

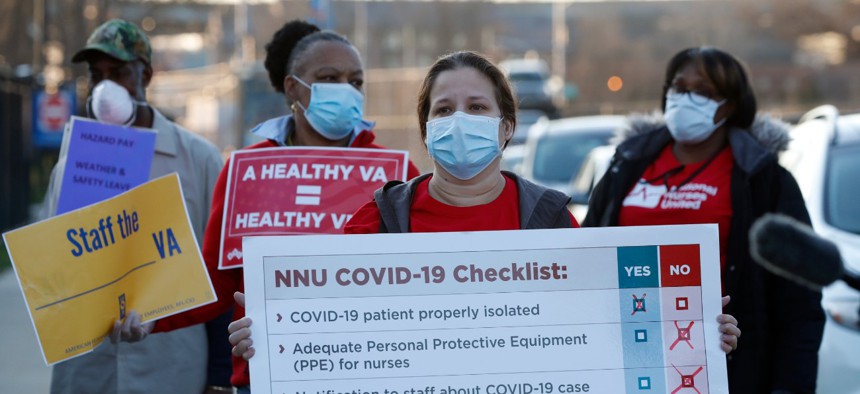

Above: Two medical providers at a VA facility in New Jersey wear their COVID protective gear into a store on the campus.

One of the Indianapolis nurses was sent home by VA because she developed symptoms. A test came back negative, however, so the facility opted to charge her for sick leave rather than administrative “safety leave,” for the time she missed, she said. She returned to work, but a few days later the symptoms worsened. She was again sent home, and now that she has exhausted her leave, is unpaid. She said she received another test on Thursday, April 16, and is awaiting results.

“At this point I really don’t care about getting paid,” she said, noting she feels an obligation to protect those around her. “I can’t go to work. It’s not fair to my patients or myself.”

‘This Is So Heartbreaking’

VA employees expressed some sympathy with management. They understand the strain the entire VA system—the largest hospital network in the country—is under, and remain committed to helping veterans, they said. While they applauded their colleagues for the service they are providing, they faulted the department for failing to act sooner to train employees to work in other units, develop a stockpile of equipment, fill staffing vacancies, and communicate new policies and potential exposures. As of April 16, 1,633 VA employees had tested positive for COVID-19 and 14 have died from the disease.

“The nurses are tired,” said one, who has worked at VA for decades. “We’re overworked. We’re overwhelmed.”

Several VA employees broke down in tears when telling their stories, typically out of concern for colleagues whose plights were worse than their own.

“This is so heartbreaking, the things that I’ve endured,” one employee said. “Not just myself. Thousands of us.”

Rhonda Risner, a registered nurse in Dayton who represents VA employees with National Nurses United, said her facility is asking her "to go against everything I learned in nursing school."

“This is the absolute worst-case scenario of anything I have ever experienced in my nursing career,” Risner said.

Another nurse cited VA management for callous leave policies and a general lack of empathy with what employees were enduring.

“You feel like you are alone,” she said, “fighting this thing alone.”