Bureau of Prisons Director Colette Peters delivers remarks after her swearing in ceremony at BOP headquarters on August 2, 2022. EVELYN HOCKSTEIN/POOL/AFP via Getty Images

Here’s How the Prisons Agency Fared During the Pandemic

The Justice Department inspector general outlined opportunities for reform before the next public health emergency.

The staffing shortage at the federal prisons’ agency is nothing new, but a new watchdog report describes the impact it had on the agency’s COVID-19 response as well as other challenges during the pandemic.

The Justice Department inspector general released a “capstone review” on Tuesday of the Federal Bureau of Prison’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic these past three years, which builds on its previous oversight work. BOP has 122 institutions nationwide, houses about 158,730 inmates and has about 34,367 employees. Like other correctional and detention institutions, it was hit particularly hard by the pandemic.

“Ongoing staffing shortages during the sustained COVID-19 pandemic had a significant and negative effect on staff morale,” said the report. “Staffing shortages have contributed to staff workload responsibilities and the BOP’s use of overtime, staffing augmentation, and reliance on [temporary duty] staff during the pandemic.”

From fiscal 2018 to fiscal 2021, BOP increased its total number of onboarded staff, but in fiscal 2022 the total number of staff declined and 21% of BOP’s budgeted correctional officer positions stayed vacant.

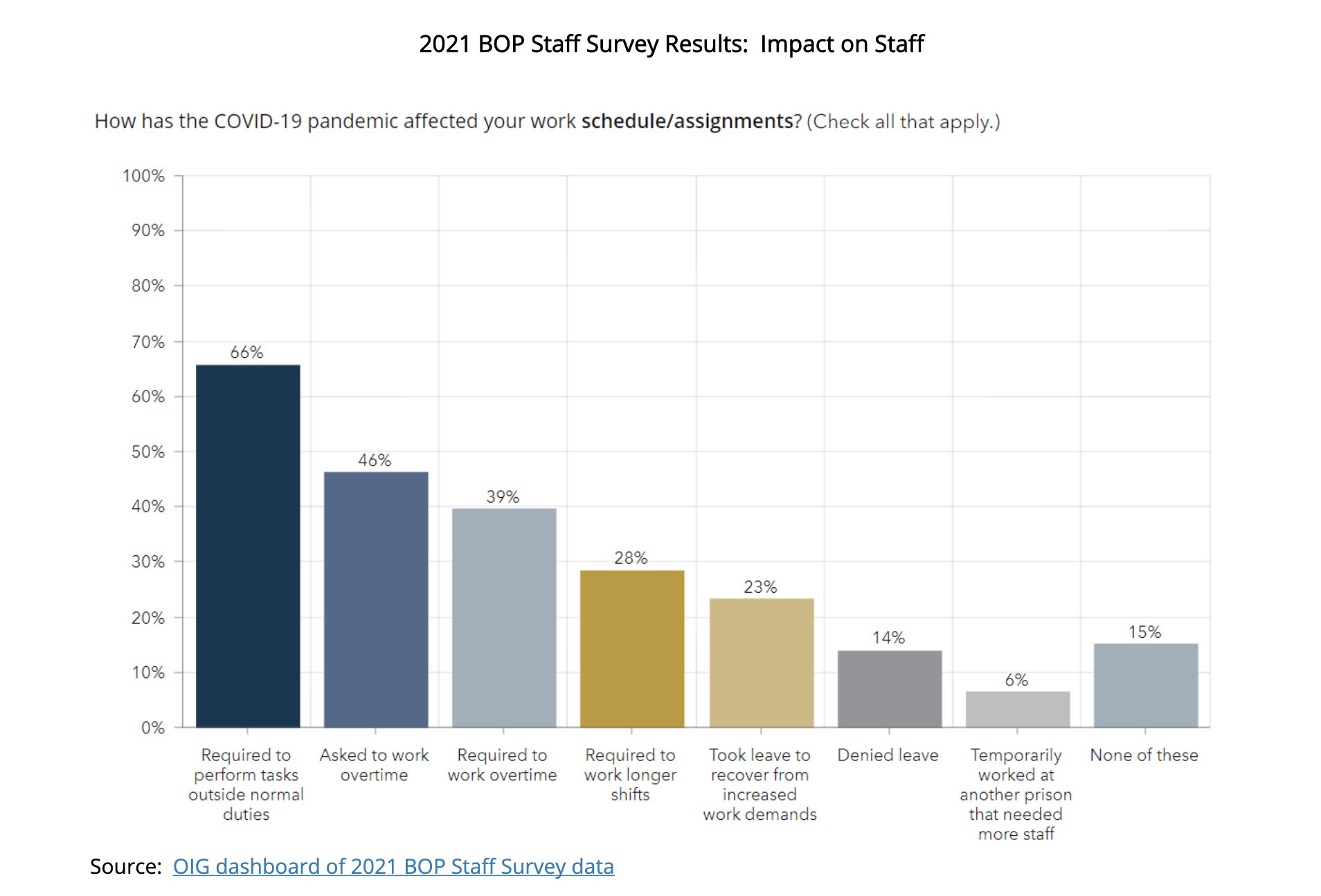

In a survey the IG conducted of BOP staff in February 2021, 66% of employees said they had to perform tasks outside of normal work duties, which included screening inmates and staff for COVID symptoms, managing quarantine and isolation units and performing tasks normally done by inmate work crews such as food service and laundry. The survey had a 19% response rate, with 6,578 responses received.

As for health service staff, 16% of those positions were vacant as of September 2020 and 14% were vacant as of September 2021.

“BOP policy states that the vacancy rate of staff positions that work directly with inmates shall not exceed 10% during any 18-month period,” the report said. “Although our remote inspections did not assess individual facilities’ compliance with this policy, we identified examples of what we believe are insufficient staffing levels, especially for Health Services staff positions, at several facilities.” As part of its work with the Pandemic Response Accountability Committee, the Justice IG is looking further at BOP’s healthcare personnel shortages during the pandemic.

Between the IG’s remote inspections and staff survey responses, the IG found mixed views on bureau leadership’s communication with employees during the pandemic. Meanwhile, there was confusion about leave and quarantine policies as they were constantly evolving.

Data Gaps

While BOP publishes on its website counts of active and recovered COVID-19 cases for inmates and staff, it did not publish a cumulative total of cases throughout the pandemic, the watchdog said. There are also certain omissions in the case data that could “lead stakeholders to draw incorrect conclusions.” There were similar issues with data on testing, the IG found.

For vaccination data, BOP posts some numbers on this, such as the total number of doses distributed and administered, but it doesn’t publish the proportion of vaccinated staff and inmates, in addition to other missing components.

Also, “unlike the BOP’s public testing and COVID-19 case data for inmates, which includes inmates in current BOP custody only, the public vaccination data includes both inmates in current BOP custody and those who have left BOP custody,” the report said. “Despite this key difference in the BOP’s reporting of COVID-19 statistics, there is no explanation on the BOP website that the presented vaccination totals include inmates who have left BOP custody. The absence of this explanation could lead stakeholders to draw incorrect conclusions.”

Other Challenges

Other findings from the IG included: quarantining and social distancing were a challenge for many BOP facilities due to the limitations of the infrastructure; BOP limited its use of home confinement for inmates (which was authorized under the CARES Act); there was a “significant deficiency” in the bureau’s communications with inmates’ families regarding serious COVID-19 cases and deaths; early on staff were confused about personal protective equipment; and there were “serious failures” in BOP facilities’ compliance with the bureau's March 2020 initial guidance on the single-celling of inmates in order to mitigate the spread of the coronavirus because numerous facilities did not adhere to the provision that single celling should be limited.

Between March 2020 and April 2021, seven inmates died by suicide while they were put in a single cell for a COVID-19 quarantine, which was followed by others. Also, despite the provision that psychology staff should be consulted for inmates proposed for single-celling, they “did not assess the suitability of single-cell assignments for at least five of the seven inmates who died by suicide prior to their single-cell placement,” said the report. “Further, postmortem documentation indicated that all seven inmates had factors that made them vulnerable to suicide.”

The watchdog stressed that in order to prepare for future public health emergencies, BOP should document its best practices and lessons learned from COVID-19. Overall, the IG issued 10 recommendations, one of which is that BOP should review its methods to engage with staff during health emergencies to make sure that the bureau is giving staff enough support and clearly communicating support options available to them.

BOP Director Colette Peters, who came to the agency last summer, agreed with the recommendation and seven others (and outlined steps they are taking or have taken to implement them). For two recommendations on single-celling, Peters did not explicitly agree or disagree. She outlined what the bureau would do to address the recommendations, but underscored for both that single-celling for medical-related isolation and quarantine isn’t restrictive housing, which is addressed separately.

“We have so much to learn from the pandemic” as “corrections professionals have said for decades that we are a public health organization,” she told Government Executive in October. Peters has also said that fixing the staffing shortage is one of her top priorities.