Soldiers attend the commencement ceremony for the U.S. Army's 2015 observance of Sexual Assault Awareness and Prevention Month in the Pentagon courtyard. Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images

‘Broken Culture’ Keeps Troops at Risk of Sexual Assault, Advocates Say

They wonder whether real change is possible before today’s leaders age out and leave.

Part 3 of "The Threat Within," a three-part series on sexual assault in the U.S. military. Read Part 1 and Part 2.

Ten years ago, Erin Kirk was in a group chat with several other female Marines when the subject of sexual harassment and sexual assault came up. Many of the women reported that they had been groped during their service; Kirk had been raped.

“We were kind of comparing notes, and had said, ‘You know, we all—at the time we were serving—felt so alone, and we thought we were the only ones’,” she told Defense One. “We were just so isolated and didn’t realize that. Why did we not realize that we all went through the exact same thing?”

The women decided to form a more official group—called Not in My Marine Corps—which started as a social media movement intended to help victims understand they are not alone and later moved into advocacy for policy change. Along the way, Kirk came to a conclusion: the military has a culture problem.

The Pentagon received 8,866 reports of sexual assault in fiscal 2021, up from 7,816 in fiscal 2020. However, based on a massive survey of troops, leaders estimate that 35,875 active duty service members “experienced some form of unwanted sexual contact” in the year prior to being surveyed—8.4 percent of active-duty women and 1.5 percent of active-duty men.

It’s not just Kirk who sees this as a problem of military culture; advocates, victims, and members of Congress agree. The Independent Review Commission on sexual assault created by Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin concluded in 2021 that “a broken culture is the root of the sexual harassment and sexual assault policy failures over the past decades.” What is less clear is exactly how to change that culture so that, as many defense leaders have repeated over the years, sexual harassment and sexual assault truly have no place in the U.S. military.

Paula Coughlin got a crash course in military culture in the mid-1980s, when she joined the Navy and went to flight school to become a helicopter pilot. But despite the harassment—the instructor who asked her to stop the simulator a little over 5,200 feet in an effort to get her to join the “Mile High Club” with him, the Marine pilot who made it clear he didn’t think women should be allowed in the military—Coughlin said she always thought she was “kind of one of the guys,” that they were “all on the same team.”

That all changed in September 1991, when Lt. Coughlin attended the Tailhook convention at the Las Vegas Hilton, as an aide to the commander of the Naval Air Test Center. While walking down the hallway of the hotel one night, she was groped and assaulted by a crowd of male Navy and Marine Corps pilots. She later told her boss about it, and though he said he would report it, she also remembers him saying, “That’s what you get when you go down a hallway full of drunk aviators,” Coughlin told PBS.

Coughlin eventually went on national television to talk about her experience, catapulting Tailhook to national scandal and making herself a pariah. The media “crucified me,” she said. “I took a beatdown…as someone who was ruining the Navy.” She resigned her commission in 1994.

More recently, Coughlin has served on the board of directors for advocacy group Protect Our Defenders. She said she “would like to think” that the culture has improved since she served.

“It’s been 30 years,” she told Defense One. “I would say, just knowing the young commander officers that I’ve known in the last few years, they are much more accepting of women in the military. So where we have these old curmudgeons who will not enforce, is top leadership. The old guys. Now, there’s exceptions to that. But until the top…the whole idea of ‘it’s nothing I wouldn’t have done, or it’s not anything I actually didn’t do when I was their age?’ That’s still there. That permissiveness comes from their own adulterated behavior.”

Rep. Jackie Speier, D-Calif., has long been a fierce advocate for overhauling the military justice system. She recalled a committee hearing about a decade ago in which the presenters discussing military sexual assault were talking about what the women were wearing and whether they had consumed alcohol.

“I thought, my God, they are back in the ’50s,” she told Defense One.

Speier later read a complaint that had been filed in federal court by veterans who were sexually assaulted while serving, and shortly afterward she began telling the stories of military sexual-assault survivors on the House floor.

“We have an obligation to protect our service members,” she said. Studies show that “sexual harassment begets sexual assault,” and “if you don’t enforce the rules and the laws, then you have sexual predators who can continue to reoffend.”

The Pentagon’s most recent report on sexual assault in the military showed that “about 2 in 5 women and 1 in 3 men” who had been sexually assaulted were sexually harassed by the same person before the assault. And the odds of experiencing sexual assault increased from 1 in 12 to 1 in 4 if they had experienced sexual harassment. For men, the odds increased from 1 in 67 to 1 in 6.

Holding people accountable is critical, because otherwise they will “think that it’s OK to keep doing it without any punishment,” and sexual assault and harassment becomes a “never-ending problem,” said Mayra Guillen, sister of Spc. Vanessa Guillen, who was murdered by a fellow soldier at Fort Hood, Texas, in 2020.

“I feel like once they actually set harsh punishments, like, hey, your career can end if you decide to touch someone…then I feel like, hey, we’re gonna take this serious, I’m not willing to lose everything,” Guillen said.

Rep. Mike Turner, R-Ohio, recognized a culture problem in the Marine Corps in 2008, after one of his constituents, Lance Cpl. Maria Lauterbach, was murdered by a coworker she had accused of rape.

“This was like the cornerstone of the really egregious cases that laid out some of the basic failures in the military system,” Turner said. While the crime itself was “horrific and tragic,” how the Marines responded to both the rape allegations and Lauterbach’s disappearance showed a “complete dehumanization of the victim.”

Since then, Turner has helped usher in a long list of modifications to the way the military handles sexual assault and harassment cases, and he said he believe the “culture has begun to change.”

“When we began this, there was the cultural view in the military that sometimes good people can do bad things. And we had to get the culture to shift to, no, sometimes criminals do criminal things, and they're caught. This is a crime. This is not just bad behavior. And it's serious. And I believe that the leadership of the Department Defense has now fully embraced that this is absolutely horrible and devastating criminal behavior.”

Don Christensen isn’t so sure. Now the president of Protect Our Defenders, he was an Air Force lawyer who served as the service’s top prosecutor from 2010 to 2014. He said that “despite all the bluster when they testify before Congress about how seriously they take this,” the military’s top leaders “just don’t believe it. They don’t believe it’s true.”

As an example, Christensen said, “What was the No. 1 concern they had when Vanessa Guillen disappeared? It wasn’t finding Vanessa. It wasn’t holding her murderer accountable when they found out it was a murder. It was deflecting that it was possibly a sexual-harassment complaint. … The boys-will-be-boys attitude, they don’t use those words anymore, but they obviously believe it.”

Of the 8,866 reports of sexual-assault made by troops in fiscal 2021, commanders considered 2,983 “for possible action.” Just 451 cases led to a court martial, and 189 resulted in a conviction, according to DOD data. The data also showed servicemember trust in the military system at an all-time low.

Kirk, of Not in My Marine Corps, said those numbers don’t inspire confidence that reporting an assault will lead to justice. This lack of trust can lead troops to leave the service.

“I mean, it says a lot about leadership. I think there is zero trust in the higher ups right now. I hate to say it, but I think that there needs to be a clean sweep pretty much across the board pretty soon,” she said. “If there’s going to be any kind of trust and confidence…there needs to be some pretty drastic measures taken.”

Gillibrand—who has been highlighting the low prosecution rates for these cases for years—said she’s met many veterans who left the service after a sexual assault, “because they weren’t taken seriously, because it so undermined their well-being that they couldn’t stay. And just, that loss of talent is so extreme. It’s a tragedy for the U.S. military and the community, as well as the individual.”

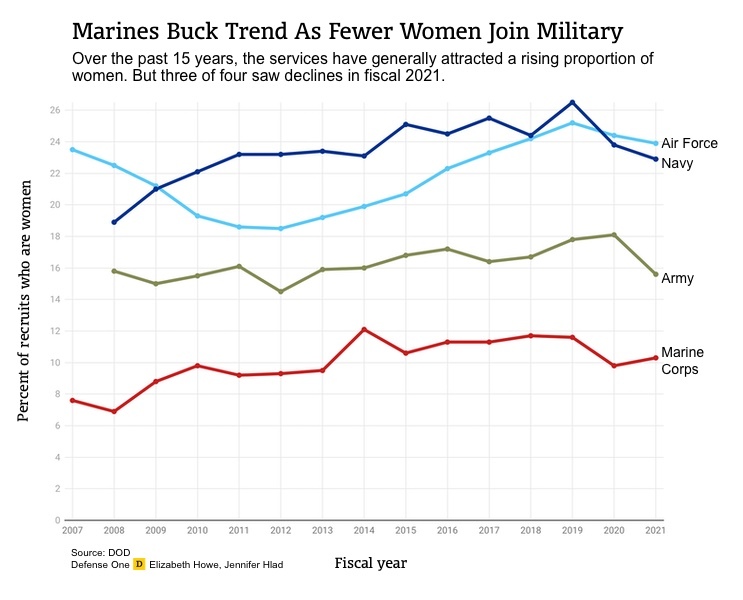

A 2021 RAND study found that “exposure to sexual assault” in the military doubled the likelihood that a service member would leave the military within 28 months. The potential effect on retention becomes even more concerning as the military faces a historic recruiting crisis. Data provided to Defense One by the military services revealed that after years of generally increasing proportions of women joining, the percentage of female recruits dipped in fiscal 2021 for the Army, Navy, and Air Force.

And while significant change is coming to the way the military handles sexual assault—including, notably, special trial counsels outside the chain of command that will handle most 11 serious crimes—most agree that more reform is needed.

“I think we’re doing well in the protection and prosecution reforms. I think prevention is the area where we need, we need more focus,” Turner said. “And some of it is to understand how we can, both in changing the culture of the military and in providing service members the tools that they need to be able to take action and actually prevent someone from committing a crime against another.”

Rachel VanLandingham, who served as an Air Force judge advocate and now teaches law at Southwestern Law School, said she hopes to see a more complete overhaul soon, rather than more “piecemeal” changes.

“Our servicemembers, who are all-volunteer and the most highly educated force that the U.S. has ever wielded, don’t they deserve the best system possible? We don’t have the best system possible,” VanLandingham said.