Federal employees walk to an entrance of the Navy Yard in Washington, D.C., as security checks credentials on Feb. 10, 2025, when many government workers were required to return to work in the office following a directive from President Donald Trump. Alex Wong/Getty Images

Trump’s return-to-office mandate exempted feds with disabilities. Many are being ordered to work in-person anyway

Some agencies have put new conditions on granting telework as a reasonable accommodation for federal employees with disabilities.

Updated at 9:30 a.m. ET Jan. 8

On his first day in office, President Donald Trump issued a directive largely ending telework and remote work for federal employees, arguing that the workplace flexibility had been abused following the COVID-19 pandemic. Qualifying civil servants with disabilities, however, were exempt from the return-to-office mandate.

The Office of Personnel Management in December reiterated this exception in its guide to telework and remote work for the federal government, noting that telework as a reasonable accommodation is distinct from an agency’s general telework policy.

Agencies are required to provide reasonable accommodations, which help enable an employee with a disability to perform a job, unless doing so would result in "undue hardship.” Common examples include interpreters, flexible schedules and accessible technology.

Still, interviews with federal employees with disabilities show that many have been ordered to in-person work. Over the past year, these individuals have been forced to contend with ever-shifting rules around agency telework, often, they say, at the expense of their mental and physical health.

“My job is 100% sedentary”

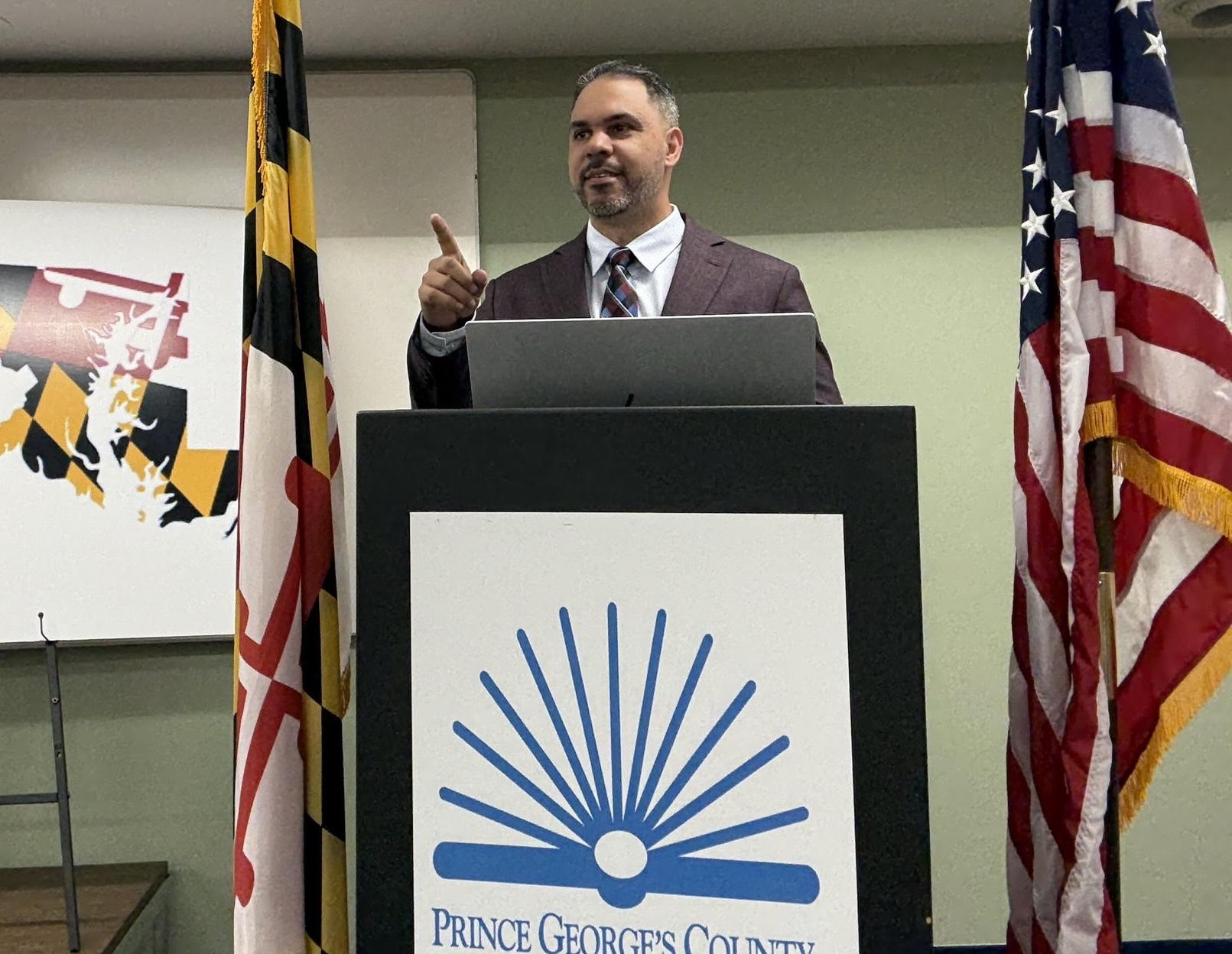

After 23 years in the Navy and more than two years as a civilian in the Defense Department working at a handful of locations across the country to find a “good fit” for his family, Terry Jackson began his “dream job” as a GS-13 physical security specialist for the Justice Department in Washington, D.C.

When he started in July 2024, his office was only required to report in-person two days per week, which helped him manage PTSD, bipolar disorder, depression and associated chronic pain symptoms when they occasionally impacted his ability "to get functional."

“There are specific mornings that I wake up where I am chronically unable to get out of bed, or it takes me a while to get out of bed and to be able to get functional,” Jackson said. “I wake up groggy a lot of mornings. I'm dizzy, lightheaded, unable to focus, have severe brain fog associated with those mental health disabilities. When they tend to flare up, it aggravates the chronic pain that I'm dealing with. So it makes it difficult in the mornings to function, especially to try to leave my house and to drive.”

But working from home helped mitigate those issues, and he said that telework didn’t impact his ability to do his job, noting that even when he was in the office meetings still happened over Microsoft Teams video conferencing.

“My job is 100% sedentary. I'm in front of a computer all day, every day,” he said. “There was nothing at home that I couldn't do that required me to be in the office.”

All that changed when Trump became president, and agencies began implementing stricter in-person work requirements.

Jackson didn’t begin working from the office full-time until May because he initially participated in the administration’s deferred resignation program for federal employees, but DOJ later approved his request to rescind his acceptance of the separation incentive. He said that working in-person five days per week was “difficult but manageable,” though he did sometimes need to use short-term medical telework or take sick leave when his symptoms flared up.

After he decided to stay at the agency, Jackson’s supervisor told him to resubmit an existing reasonable accommodation he had that permitted flexible hours (e.g. 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. instead of 8 a.m. to 4 p.m.) to ensure it aligned with the return-to-office policy. So Jackson on May 22, 2025, included in his submission a request to telework three days per week like he did prior to the policy change under the Trump administration. His request for telework was denied after three business days because, according to the document, the accommodation would remove an essential function of his position.

Eric Pines, an attorney who specializes in representing federal employees with disabilities, said that a rejection after three days to a reasonable accommodation request for telework would be the quickest response he’s seen in his 30-year career.

“This is definitely unusual,” he told Government Executive by email. “I would be very suspicious that it was not reviewed properly.”

“It just caught me off guard”

While Jackson was appealing the reasonable accommodation denial, he was also contending with the Trump administration’s mass firing of probationary employees, generally those who have been hired or promoted in the government within the past one to two years. Despite being a probationary worker, he was not impacted by the removals. He did, however, take note of an April executive order requiring agencies to affirmatively decide whether to retain employees once their probationary periods end.

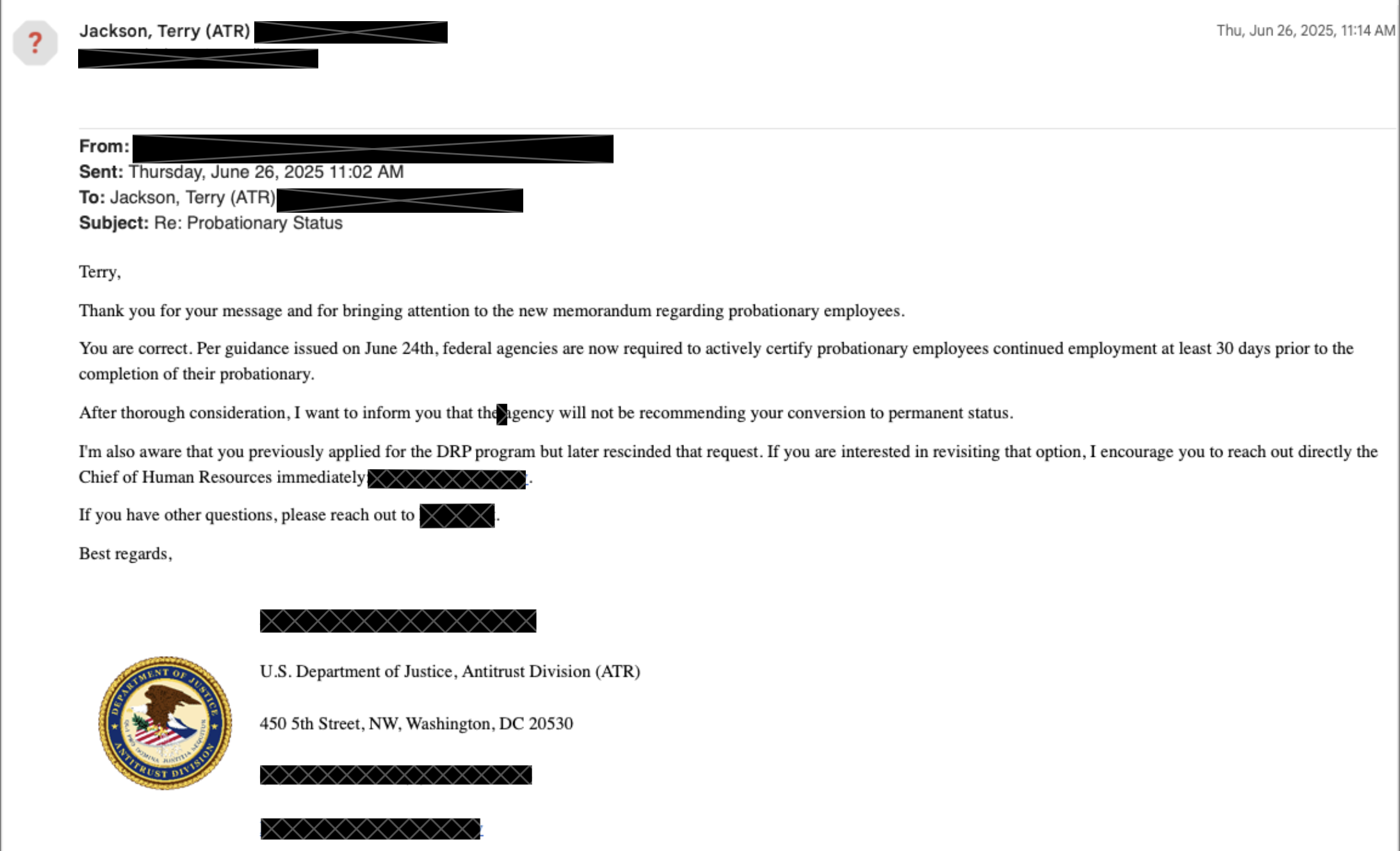

On June 26, 2025, about a month before the end of his probationary period, Jackson emailed his supervisor to ask if he would be staying on at DOJ. His supervisor responded the same day that “the agency will not be recommending [Jackson’s] conversion to permanent status.” Jackson’s access to the building and network were revoked shortly thereafter.

When Jackson asked human resources officials why he was being terminated, they responded that it was due to “security concerns with [his] professional conduct.” He said that he never received any disciplinary write-ups.

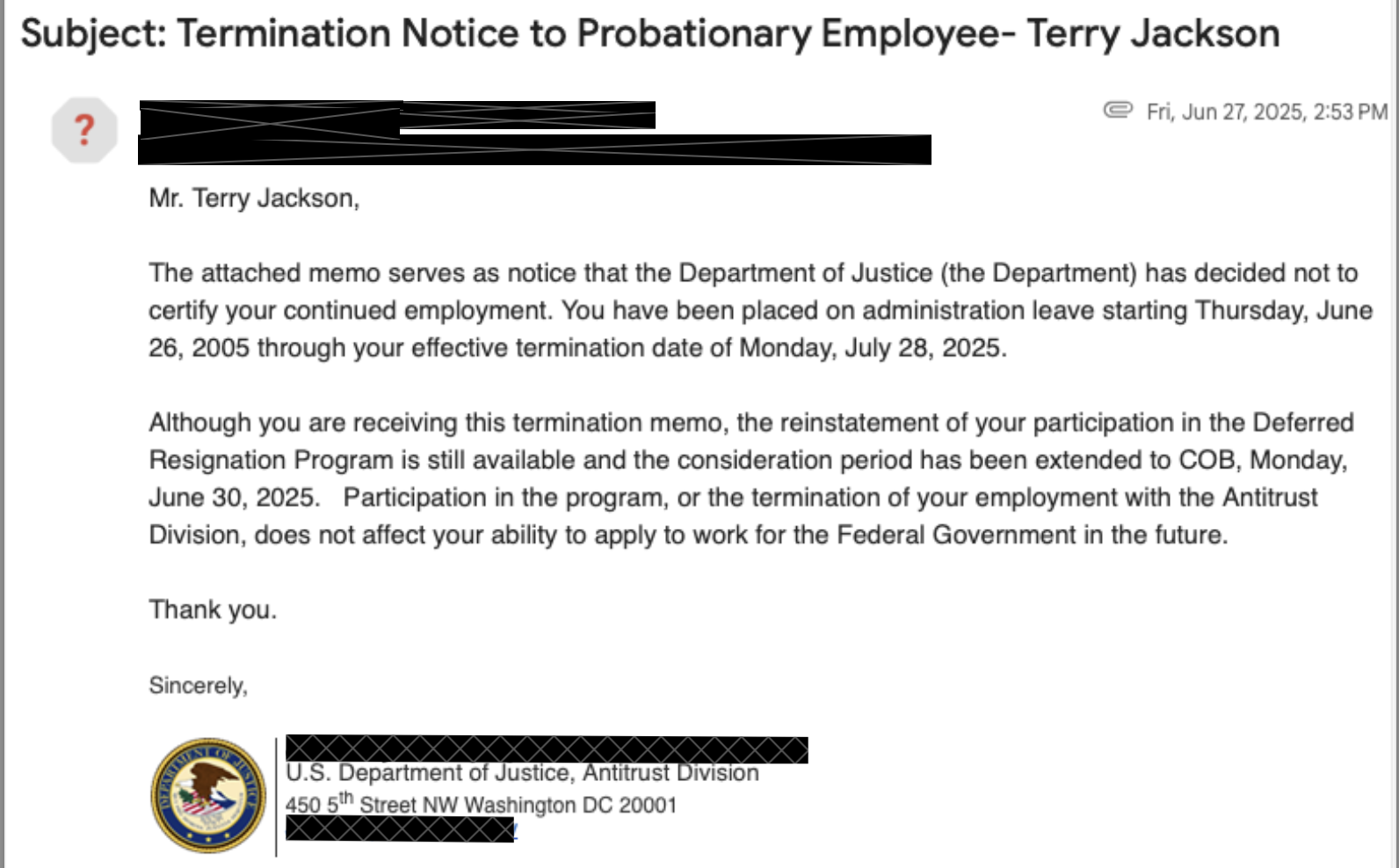

DOJ on June 27, 2025, sent him a notice that he was being put on administrative leave until the end of his probationary period, which was July 28, 2025. Due to a typo, the email said that his leave began on June 26, 2005. The notice also said that he still had the option to participate in DRP.

“It happened so quick, and it was out of nowhere and it just caught me off guard. It sent me into a depressive/bipolar episodic situation,” Jackson said. “I was spinning out because I couldn't wrap my mind around what was happening, why it was happening, what was the cause of it?”

Due to a psychiatric episode, he ended up involuntarily spending three days at a behavioral health facility.

In a twist, however, on July 16, 2025, Jackson received a notice that his termination was being rescinded. After his hospitalization, Jackson took medical leave, so he didn’t return to work until August 2025.

He described going back to his job as "very awkward." Once again, he requested a reasonable accommodation for telework.

“They had more medical documents because they had my [Family and Medical Leave Act] paperwork, so they knew that my conditions were legitimate and they were real,” Jackson said. “So I figured, ‘I'll put a reasonable accommodation in again, and this time it should go through no problem because they understand that this is a real situation that I'm dealing with.’”

It was denied. But DOJ did approve his request for situational telework for “temporary illness or injury” that allowed him to work from home for 30 days. This was more generous than his reasonable accommodation request, in which he was only asking for episodic telework for days when his medical symptoms flared up.

“I found that funny because they denied my reasonable accommodation request because they said my position required me to be on site, but yet here they go giving me a full 30-day block of telework,” he said.

Jackson said during that month there was little communication with his supervisor and that he received few new assignments.

Ultimately, Jackson said that he left government service in October 2025 under the terms of a six-figure settlement with DOJ that resolved claims of disability discrimination, retaliation and prohibited personnel practices, among other allegations.

“I thought it would be a different dynamic when I went back after being terminated, but there was no remorse on behalf of the agency. They treated me kind of neutral, like nothing mattered, like everything was fine,” he said. “I was just supposed to come back and accept the fact that they gave me my job back, even though they incorrectly terminated me and did the things that they did.”

DOJ did not respond to a request for comment.

While Jackson has left the civil service, he is interested in returning to government. He’s currently running for Congress as a Democrat to represent Maryland’s Fifth District, which is currently represented by Steny Hoyer. Also a Democrat, Hoyer told The Washington Post for an article published Tuesday night that he will not run for reelection.

Jackson said that his decision to run is not specifically related to his experience at DOJ.

“I was provided with an opening because I don’t have a job anymore. And I've experienced how government works,” he said. “So given that, I want to take these experiences that I have had — being in the military, being a federal employee, seeing how government works — I have the lived experience that I can take with me to Congress, and I can advocate for people who experience these types of situations.”

“Feels like a way of punishing us”

Jackson’s experience is part of a broader trend of federal employees struggling to obtain reasonable accommodations for telework under the return-to-office order.

Government Executive spoke with a Defense Department employee who in summer 2025 was approved for a partial telework reasonable accommodation, but it was rescinded a couple weeks later. The individual said officials told her the reversal was due to Trump’s memo ending work from home, even though that directive was in effect when their reasonable accommodation was initially cleared.

While the employee has appealed DOD’s decision, they’ve been working full-time from the office since the end of the government shutdown in November 2025.

“It’s been turbulent, for sure. Very stressful. I cry a lot, which does not help my mental health,” the employee said. “I like my job, but this year has just been awful.”

In a follow-up message, the employee said that they’ve since been granted an interim reasonable accommodation for telework.

Additionally, some agencies have put new conditions on granting telework reasonable accommodations.

The Health and Human Services Department in September began requiring officials at the assistant secretary level or above, rather than supervisors, to approve telework requests.

This policy change forced a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention employee — who started working for the federal government under Schedule A, an authority for hiring individuals with disabilities — to return to the office full-time.

This employee told Government Executive that they submitted a reasonable accommodation request for partial telework in summer 2025 but didn’t get a response until December, and that was simply an acknowledgement of receipt.

CDC’s union in September accused officials of not processing reasonable accommodation requests due to layoffs at the agency’s Equal Employment Opportunity Office.

While the employee was waiting to hear back about their reasonable accommodation request, their supervisor had been approving them for partial telework on an interim basis.

“When we started coming back to the office full-time [in spring 2025], I realized I was having more flare ups of this chronic condition that I have, so I requested part-time-telework,” the employee said. “By teleworking two days a week, I was able to really manage a lot of the problems that were coming up physically.”

Since having to work full-time in-person due to the September policy change, the employee said they’re “having a lot more physical health challenges than I would typically expect.”

CDC workers were permitted to telework for about a month following an August 2025 shooting at the agency’s Atlanta headquarters that killed a responding police officer. The employee, however, said that when staff were ordered to return in September the bullet holes still hadn’t been removed and were covered in paper.

HHS said in a statement to Government Executive that the September policy “establishes department-wide procedures to ensure consistency with federal law” and that officials “remain committed to processing [reasonable accommodation] requests as quickly as possible.”

The department also said that reasonable accommodations for telework can be granted on an interim basis, however, those also must be approved by an official at least at the assistant secretary level. HHS did not address a question about the state of repairs at CDC’s headquarters following the shooting.

The Veterans Affairs Department in June began requiring a member of the senior executive service to sign off on certain telework reasonable accommodation requests and supervisors to annually review approved reasonable accommodations in order to “maximize” in-person work. VA did not respond to a request for comment about the results of these policy changes.

And the IRS, as a result of the return-to-office directive, is putting new restrictions on employees who request telework due to temporary hardship, according to a report from Federal News Network.

The CDC employee described the crackdown on telework reasonable accommodations as a “restriction of freedom.”

“It feels like a way of punishing us,” they said.

This story has been updated with the development that Rep. Steny Hoyer, D-Md., will not run for reelection.

Share your news tips with us: Sean Michael Newhouse: snewhouse@govexec.com, Signal: seanthenewsboy.45

NEXT STORY: Democrats decry reports that Trump will further slash FEMA's workforce