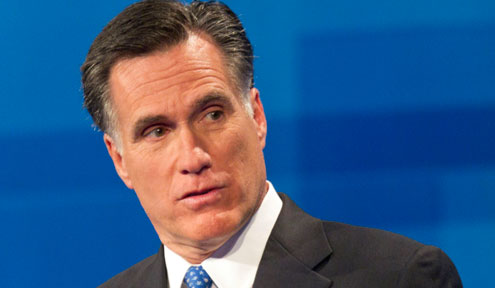

GOP's managerial wing picks its man -- Romney

Newt Gingrich's ringing declarations to shutter federal departments may not be enough to help him overtake the Republican front-runner in South Carolina.

David Goldman/AP

COLUMBIA, S.C. -- In the crowd milling outside the South Carolina Chamber of Commerce's annual "Business Speaks" conference at a downtown hotel here on Tuesday, there were not many effusive declarations of support for Republican presidential front-runner Mitt Romney.

But from the perspective of the candidates chasing Romney -- most of whom addressed the meeting -- the chatter in the hallways conveyed something even more ominous: a sense of acceptance about the likelihood of his nomination, and little inclination to extend the race by denying him a victory in Saturday's pivotal South Carolina primary.

"A lot of our guys are still undecided, but I think most people are coalescing around Romney now because they think he's the one guy who can bring all the groups together," said Otis Rawl, president and CEO of the state chamber. "A lot of that is crystallizing in the last three or four days."

Romney did not attend the Chamber's presidential forum here Tuesday afternoon. Many of those in the room agreed that former House Speaker Newt Gingrich delivered a scintillating performance, replete with ringing declarations to shutter federal departments from the Environmental Protection Agency to the National Labor Relations Board, and far outshone the other two candidates who spoke, Texas Gov. Rick Perry and former Pennsylvania Sen. Rick Santorum.

"Newt kicked their rear ends," said Bill Anglin of Mt. Holley after the forum. "We were ready to grab the bayonets and yell 'Charge.'"

But admiration didn't necessarily translate into support. Like voters in Iowa and New Hampshire, activists in South Carolina are well aware of their influence; they know the state has picked the winner in every contested Republican presidential race since 1980. In his remarks, Gingrich appealed to that sense of gravity by flatly declaring that if he wins South Carolina, he will overcome Romney and seize the nomination.

That proposition is debatable: This year it's not clear that even a last-ditch South Carolina victory for Gingrich would overcome Romney's other financial and organizational advantages. More importantly, several of those I spoke to outside the Chamber event seemed inclined to use the state's influence not to extend the GOP race but to end it -- and turn the focus toward President Obama.

Few may describe Romney with terms of endearment, but the predominant attitude expressed toward him here wasn't one of mere resignation. For most of those I spoke with he crosses the threshold as an acceptable nominee, and after comparing him to the field that has sparred through 16 debates, that's good enough.

Robert Marlowe, the senior vice president for development at the College of Charleston, said he sees the same drift toward the front-runner that Rawl detected. "I was at a lunch today with a group of people and they were all settling on Romney and they had not previously decided," Marlowe said. "They felt he was the most well-rounded and electable."

In one sense, that's not surprising: Business groups like these are Romney's most natural audience. But the movement toward him in the Columbia group encapsulates his steady progress at consolidating the more economically-focused, pragmatic and college-educated half of the GOP coalition -- what I've called the party's managerial wing.

This week's ABC/Washington Post national poll documents that movement, with results showing Romney (who had long been stuck around 25 percent overall) moving toward support of 40 percent or more among college-educated Republicans, moderates and those who do not describe themselves as strong supporters of the tea party. A Monmouth University poll in South Carolina released Tuesday likewise found Romney approaching 40 percent among state voters who do not identify as evangelical Christians, as well as those who consider themselves only somewhat conservative or moderate, and those who are not strong tea party supporters.

The smooth and affluent Romney still faces plenty of skepticism over everything from his commitment to conservative causes to his style in the other half of the party-the more blue-collar and socially conservative wing that I've termed the GOP populists. At a Gingrich event later Tuesday night in Aiken, about an hour outside of Columbia, Anne Fulcher, a health care worker, practically pursed her lips when asked about Romney.

"There's something disconcerting about his looks," she said. "He's a lot of show. He gives me the impression of being too perfect. I usually can spot someone who is putting in airs." The attacks on Romney's record at Bain may be resonating more powerfully with these voters.

By contrast, in their wing tips and pinstripes, the business executives and entrepreneurs gathering in Columbia related easily to Romney's background as a manager at Bain Capital -- and recoil from the attacks on his record in the firm from Gingrich and Perry.

In response to a question here, Gingrich delivered as crisp and compelling a case against Bain as he has offered anywhere. Yet the Chamber audience phrased the questions to both Gingrich and Perry about the Bain attacks in a way that betrayed obvious skepticism about their arguments. And afterwards, Marlowe was one of several who said the Bain attacks had provoked a backlash against Perry and Gingrich.

"In a capitalistic society, people fire people all the time," he said. "People who had been supporting the other candidates don't like it."

Its hardly scientific, but the tilt toward Romney at the Chamber meeting reaffirmed the central dynamic that has governed the GOP race since December: Romney is consolidating the more pragmatic and centrist managerial wing of the party behind him more than anyone is consolidating the more conservative and populist wing against him. That disparity isn't enough to produce a stampede toward Romney but it continues to provide him with a steady advantage in a fractured field-one that could prove decisive if one of his opponents can't rally for a last stand here on Saturday.

Josh Kraushaar contributed to this report.