Trump Wasn't the First President to Try to Politicize the Civil Service – Which Remains at Risk of Returning to Jackson’s ‘Spoils System’

For decades, presidents beginning with Andrew Jackson routinely replaced large swaths of the government workforce, often requiring them to pay fees to political parties in exchange for their jobs.

The federal government’s core civilian workforce has long been known for its professionalism. About 2.1 million nonpartisan career officials provide essential public services in such diverse areas as agriculture, national parks, defense, homeland security, environmental protection and veterans’ affairs.

To get the vast majority of these “competitive service” jobs – which are protected from easy firing – federal employees must demonstrate achievement in job-specific knowledge, skills and abilities superior to other applicants and, in some cases, pass an exam. In other words, the civil service is designed to be “merit-based.”

It wasn’t always so.

From Andrew Jackson until Theodore Roosevelt, much of the federal workforce was subject to change after every presidential election – and often did. Known as the spoils system, this pattern of political patronage, in which officeholders award allies with jobs in return for support, began to end in the late 19th century as citizens and politicians like Roosevelt grew fed up with its corruption, incompetence and inefficiency – and its role in the assassination of a president.

Less than two weeks before Election Day, former President Donald Trump signed an executive order that threatened to return the U.S. to a spoils system in which a large share of the federal government’s workforce could be fired for little or no reason – including a perceived lack of loyalty to the president.

While President Joe Biden quickly reversed the order soon after taking office, the incident shows just how vulnerable the civil service is.

Birth of the spoils system

The government of the early republic was small, but the issue of whether civil servants should be chosen on the basis of patronage or skills was hotly debated.

Although George Washington and the five presidents who followed him certainly employed patronage, they emphasized merit when making appointments.

Washington wrote that relying on one’s personal relationship to the applicant would constitute “an absolute bar to preferment” and wanted those “as in my judgment shall be the best qualified to discharge the functions of the departments to which they shall be appointed.” He would not even appoint his own soldiers to government positions if they lacked the necessary qualifications.

That changed in 1829 when Andrew Jackson, the seventh president, entered the White House

Jackson came to office as a reformer with a promise to end the dominance of elites and what he considered their corrupt policies. He believed that popular access to government jobs – and their frequent turnover through a four-year “rotation in office” – could serve ideals of democratic participation, regardless of one’s qualifications for a position.

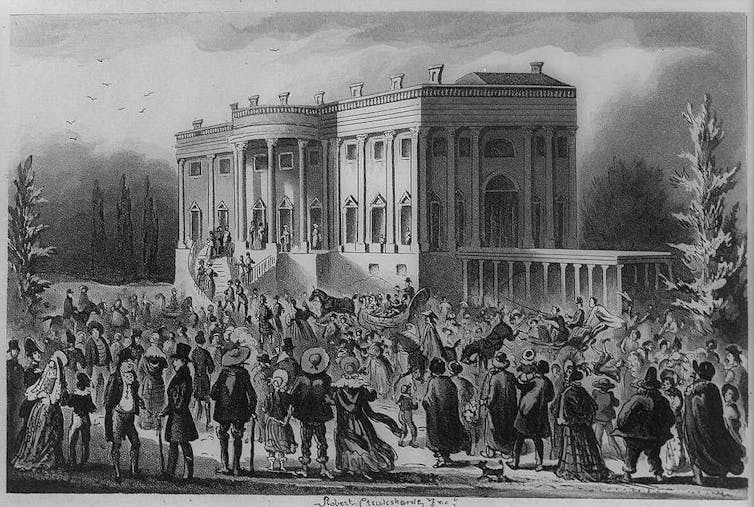

As a result, at his inaugural reception on March 4, a huge crowd of office seekers crashed the reception. Jackson was “besieged by applicants” and “battalions of hopefuls,” all seeking government jobs.

Instead of preventing corruption from taking root, Jackson’s rotation policy became an opportunity for patronage – or rewarding supporters with the spoils of victory. He defended the practice by declaring: “If my personal friends are qualified and patriotic, why should I not be permitted to bestow a few offices on them?”

Besides possessing a lack of appropriate skills and commitment, office seekers were expected to pay “assessments” – a percentage of their salary ranging from 2% to 7% – to the party that appointed them.

Although Jackson replaced only about 10% of the federal workforce and 41% of presidential appointments, the practice increasingly became the norm as subsequent presidents fired as well as refused to reappoint ever-larger shares of the government.

The peak of the spoils system came under James Buchanan, who served from 1857 to 1861. He replaced virtually every federal worker at the end of their “rotation.” William L. Marcy, who was secretary of state under Buchanan’s predecessor and was the first to refer to patronage as “spoils,” wrote in 1857 that civil servants from his administration were being “hunted down like wild beasts.”

Even Abraham Lincoln, who followed Buchanan, made extensive use of the system, replacing at least 1,457 of the 1,639 officials then subject to presidential appointment. The number would have been higher but for the secession of Southern states, which put some federal officials out of his reach.

A ‘vast public evil’ comes to an end

The tide began to turn in the late 1860s following public revelations that positions had been created requiring little or no work and other abuses, including illiterate appointees, and a congressional report about the success of civil service systems in Great Britain, China, France and Prussia.

In 1870, President Ulysses S. Grant asked Congress to take action, complaining, “The present system does not secure the best men, and often not even fit men, for public place.” Congress responded with legislation that authorized the president to use executive orders to prescribe regulations for the civil service. That power exists today, most recently exercised in Trump’s own order.

Grant established a Civil Service Commission that led to some reforms, but just two years later a hostile Congress cut off new funding, and Grant terminated the experiment in March 1875. The number of jobs potentially open to patronage continued to soar, doubling from 51,020 in 1871 to 100,020 in 1881.

But across the U.S., citizens were becoming disgusted by a government stuffed with the people known as “spoilsmen,” leading to a growing reform movement. The assassination of President James Garfield in 1881 by a deranged office seeker who felt Garfield had denied him the Paris diplomatic post he wanted pushed the movement over the edge.

Garfield’s murder was widely blamed on the spoils system. George William Curtis, editor of Harper’s Weekly and an advocate for reform, published cartoons lambasting the system and called it “a vast public evil.”

In early 1883, immediately after an election that led to sweeping gains for politicians in favor of reform, Congress passed the Pendleton Act. It created the civil service system of merit-based selection and promotion. The act banned “assessments,” implemented competitive exams and open competitions for jobs, and prevented civil servants from being fired for political reasons.

Roosevelt was appointed to the new commission that oversaw the system by President Benjamin Harrison in 1889 and quickly became its driving force – even as Harrison himself abused the spoils system, replacing 43,823 out of 58,623 postmasters, for example.

At first, the system covered just 10.5% of the federal workforce, but it was gradually expanded to cover most workers. Under Roosevelt, who became president in 1901 after William McKinley was assassinated, the number of covered employees finally exceeded those not covered in 1904 and soon reached almost two-thirds of all federal jobs. At its peak in the 1950s, the competitive civil service covered almost 90% of federal employees.

New York, where Roosevelt was an assemblyman, and Massachusetts were the first states to implement their own civil service systems. Although all states now have such systems in place at local, state or both levels, it was not until after 1940 that most states adopted a competitive civil service.

Teddy’s unfinished work

Trump’s Oct. 21 executive order would have undone over a century of reforms by stripping potentially hundreds of thousands of civil servants of the protections that keep them from being summarily fired for political reasons. Insufficient loyalty to the president would be enough to lose one’s job.

Biden revoked the changes two days after taking office, but the episode is a reminder just how fragile the system supporting a merit-based government workforce remains.

While Trump’s effort to meddle in the civil service was particularly brazen, administrations of both parties still have a habit of doing so. For example, a common practice of outgoing administrations – including Trump’s – is to convert political appointees into permanent and protected civil servants in a process known as “burrowing.” Whether an effort to plant people who can carry on a previous administration’s policies or simply meant as a patronage reward, such appointees can be very hard for the incoming one to remove.

Both Trump’s executive order and the bipartisan practice of burrowing show the civil service needs stronger protections and that Teddy Roosevelt’s work is still unfinished. If, on a whim, a president can undo over a century of reforms, then the civil service remains insufficiently insulated from politics and patronage.

It may be time Congress passed a new law that permanently shields one of America’s proudest achievements from becoming another dysfunctional part of the U.S. government.

This is an updated version of an article originally published on Jan. 21, 2021.

![]()