jan kranendonk/Shutterstock.com

Baby Boomers Were Job-Hopping Before It Was Cool

New data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics shows that the notion of the "company man" died not recently, but long ago.

If you haven't already bid farewell to the concept of the “company man,” you definitely missed your chance.

A new study from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics shows that the already aged concept of a "good job for life" went away long before the rise of the “job-hopping Millennial” (or Gen-X-er, for that matter). In fact, workers who hold multiple jobs in one lifetime became normal as early as the mid-1970s, with the Baby Boom generation. The BLS finds that the average American born between 1957 and 1964—the latter years of the baby boom—held nearly a dozen (11.7) jobs between the ages of 18 and 48. Job security hasn’t been a guarantee for at least the past 40 years.

The BLS data draws from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1979 , an ongoing survey that first interviewed nearly 10,000 men and women between the ages of 14 and 22 in 1979. During the latest round of interviews, in 2012 and 2013, the respondents were between 47 and 56. Interviews queried the respondents on a number of issues, including work experiences, educational attainment, income, and health. The report notes that it considers the responses of these survey participants to be “representative of all men and women born in the late 1950s and early 1960s and living in the United States when the survey began in 1979.”

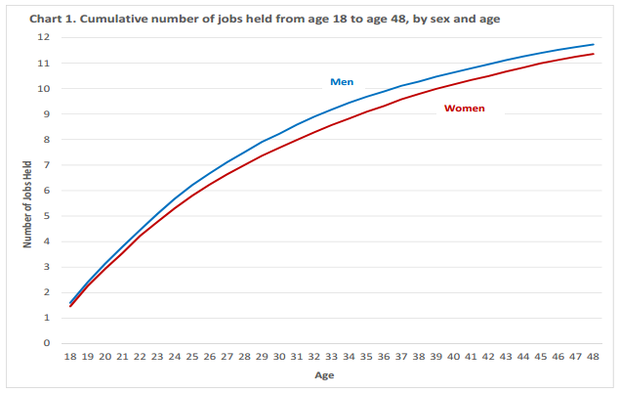

The chart below, from the report, shows the average young-boomer’s job trajectory between 18 and 48. The curve climbs steeply in the first six or so years of their careers, between 18 and 24, when the average respondent had 5.5 jobs. The duration of each job lengthened as the boomers got older, which makes sense—it tends to take longer to move up the job ladder the closer one gets to the top. The average boomer held three jobs between 25 and 29, 2.4 between 30 to 34, 2.1 between 35 to 39, and 2.4 in the eight-year span between 40 and 48.

The report also breaks down the later boomers’ career trajectories by gender, education level, and race. Women held slightly fewer jobs than men overall—11.5 on average between 18 and 48, compared to 11.8 for men. Interestingly enough, women with bachelor’s degrees were more likely to job-hop than their similarly educated male peers: They held an average 12.5 jobs between 18 and 48, compared to 11.2 for men. Men without high school diplomas, meanwhile, changed jobs the most, an average 12.9 times, compared to only 9.6 times for high school graduate women.

Job mobility also differed by race, but only among the young. Between 18 and 24, the study found that white boomers changed jobs more often (5.7 times) than blacks or Hispanics (4.6 and 4.9 times, respectively). But from 25 to 48, the difference evened out, and whites were not significantly more likely to change jobs than blacks or Hispanics.

*****

For all the talk of Millennials’ excessive job-hopping ways, it seems the precedent was set long ago—by their parents. But there’s an important difference between the economy these later boomers faced and the one with which their children are now grappling. According to the report, the hourly earnings of boomers increased more rapidly while they were young. Between 18 and 24, these workers saw their earnings jump by an average 6.2 percent per year. Those with bachelor’s degrees saw even greater yearly jumps, by 9.4 percent annually between 18 and 24. Predictably, those earnings increases slowed down as boomers got older, with earnings growth rates decreasing from an average 4.1 percent annually between 25 and 29 to just 0.7 percent between 40 and 48. The bulk of boomers’ wage growth, then, happened when they were young.

This would seem to reinforce the idea that the Great Recession permanently damaged the earning potential of young people today. A 2013 Urban Institute report shows that the average wealth of those between 20 and 30 in 2010 was 7 percent lower than the average wealth of boomers in their 20s and 30s in 1983. This is particularly troubling given the pattern for boomers, who saw substantial earning gains in the early years of their careers.

Even as more jobs become available and Millennials’ careers pick up steam with the economic recovery, young people who came of working age during the years of the Great Recession are likely to see permanent damage to their lifetime earnings. This is bad news for them, but it’s also bad news for the entire national economy.

( Image via jan kranendonk / Shutterstock.com )