Since the 1970s, medicine and computers have reigned over patents like no two categories have dominated any previous period of invention in U.S. history. Wutthichai/Shutterstock.com

'From Atoms to Bits': A Brilliant Visual History of American Ideas

A new paper employs a simple technique—counting words in patent texts—to trace the history of American invention, from chemistry to computers.

One night in the the spring of 1983, the scientist Kary Mullis was driving with his girlfriend along Highway 128 from Berkeley to Mendocino, California. As Mullis took in the perfume of California buckeyes swinging their blossoms along the road, his mind wandered back to his job as a chemist . He was thinking about human DNA. Specifically, he was thinking about how to replicate human DNA. And it was there, at "mile marker 46.7 on Highway 128,” as he specified a decade later in his Nobel Lecture , that he experienced that rare and often apocryphal moment of invention—a eureka .

Actually, it was a kind of rolling eureka, a rapid-fire series of bingo moments. Mullis would later name his idea “polymerase chain reaction,” or PCR. It was, to oversimplify greatly, the singular invention that made possible that mass duplication of short sequences of DNA. It is a technology behind cloning, gene sequencing, identifying hereditary diseases, making velociraptors in Jurassic Park , and catching criminals in CSI (both in the shows and in real life). In the 1990s, the London Observer suggested it was the most "momentous idea” of the past two centuries .

But was it, really? Was it more significant than the transistor, or the microprocessor, or the World Wide Web? More importantly, how would an enthusiast of American ideas (as The Atlantic has proudly been for a century and a half ) measure something as ineffable as the significance of a new invention? In fact, in a new paper, Mikko Packalen at the University of Waterloo and Jay Bhattacharya of Stanford University, devised a brilliant way to address this question empirically. In short, they counted words in patent texts .

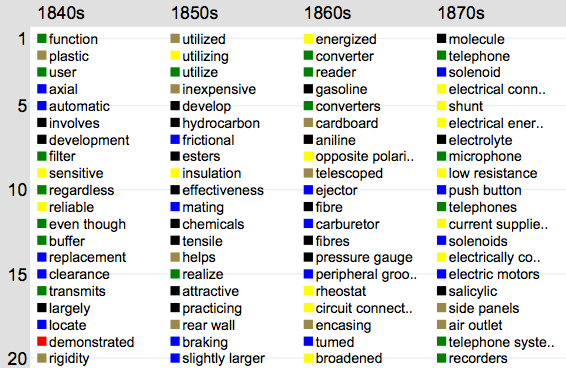

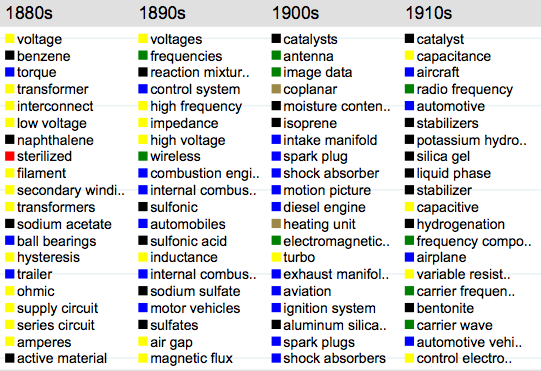

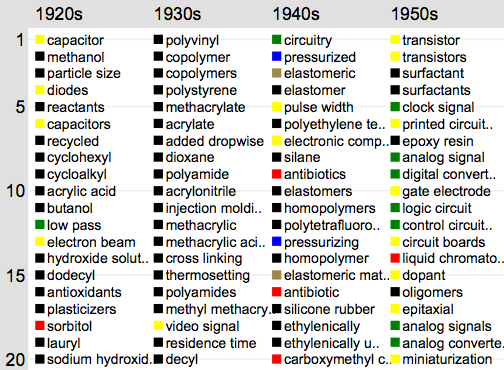

In a series of papers studying the history of American innovation, Packalen and Bhattacharya indexed every one-word, two-word, and three-word phrase that appeared in more than 4 million patent texts in the last 175 years. To focus their search on truly new concepts, they recorded the year those phrases first appeared in a patent. Finally, they ranked each concept's popularity based on how many times it reappeared in later patents. Essentially, they trawled the billion-word literature of patents to document the birth-year and the lifespan of American concepts, from "plastic" to "world wide web" and "instant messaging."

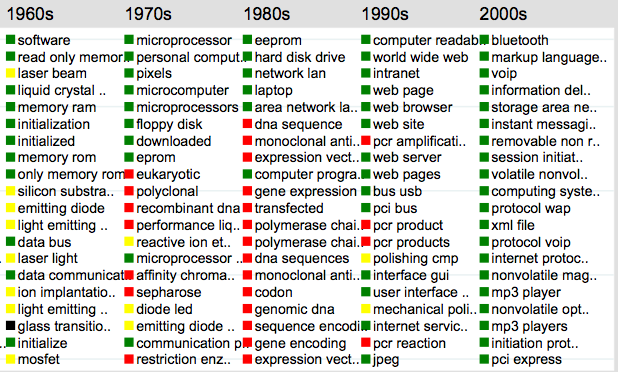

Here are the 20 most popular sequences of words in each decade from the 1840s to the 2000s. You can see polymerase chain reactions in the middle of the 1980s stack. Since the timeline, as it appears in the paper, is too wide to be visible on this article page, I've chopped it up and inserted the color code both above and below the timeline.

A Brief Visual History of American Ideas

The overall story, Bhattacharya told me, follows the shift from "atoms to bits"—from the loud world of trains and cars in the 19th century to the invisible life of software. But within that meta-narrative (and this is where the colors come in handy), you can see moments where one industry dominated the patent literature—like chemistry (black) in the 1930s, medicine (red) in the 1980s, and computers (green) in the last few decades.

Since the 1970s, medicine and computers have reigned over patents like no two categories have dominated any previous period of invention in U.S. history. In his Nobel address, Mullis described his midnight eureka as a solitary moment of invention on an lonely California road. But rather than seeing him as a lonely inventor, it might make more sense to view him as a product of his times, a medical scientist working in the 1980s, at the apex of medicine's potency in the patent literature. His PCR patent was a part of, and a catalyst for, its own chain reaction of innovation in genetics, from "genomic DNA" to "DNA sequencing" to "monoclonal antibodies." Patents that introduce entirely new fields of study (like PCR) spur much more new research than subtle tweaks to old ideas, Packalen and Bhattacharya found. Still, past research has shown that organizations like the National Institutes of Health and the National Science Foundation are more likely to subsidize projects in highly familiar areas. Indeed, one of the major implications of Packalen and Bhattacharya's research is that, by awarding established scientists in well-understood fields, the government is implicitly discouraging the most radical innovation.

Another theme of Packalen and Bhattacharya's research is that innovation has become more collaborative. Indeed, computers have not only taken over the world of inventions, but also they have changed the geography of innovation, Bhattacharya said. Larger cities have historically held an innovative advantage, because (the theory goes) their density of smarties speeds up debate on the merits of new ideas, which are often born raw and poorly understood. But the researchers found that in the last few decades, larger cities are no more likely to produce new ideas in patents than smaller cities that can just as easily connect online with their co-authors. "Perhaps due to the Internet, the advantage of larger cities appears to be eroding,” Packalen wrote in an email.

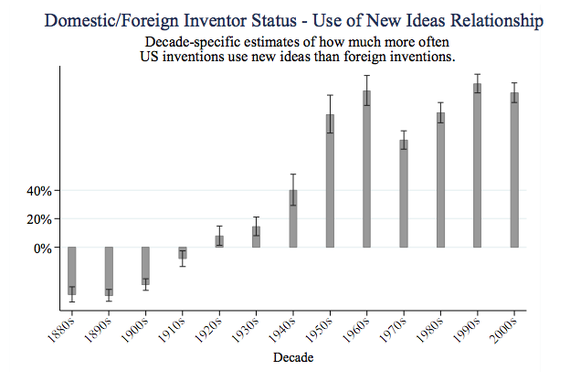

Bhattacharya didn't want me to go away with the impression that he thought something about the American invention machine was broken. He pointed out that patents with first-name authors living in the United States were considerably more likely to introduce new concepts than those with foreign authors today, a clear reversal since the 19th century.

U.S. Invention: From Follower to Leader

The good news, Bhattacharya said, is that this picture provides clear evidence that although the United States often followed the world in chemical and electrical innovation in the late 19th century, today's American inventors are far more likely than Edison and Einstein's generations at coming up with truly new ideas that haven't been picked to death. "There’s still something in the American culture that emphasizes invention," he said.

( Image via Wutthichai / Shutterstock.com )