White House file photo

What's the largest category of government spending?

If you ask a normal person, she might tell you it's Medicare (close), Defense (closer), or even foreign aid (c'mon). But there's another category of the budget that's even larger. The trick is, it's not a form of spending at all. It's called tax expenditures .

When the government writes a law that takes your money, that's a tax. When it creates an exception to that law, it's a tax expenditure. To take a simple example: You pay taxes on your work compensation—like Social Security taxes and federal income taxes—but you don't pay taxes on employer-sponsored health insurance, even though that's clearly a part of your compensation. This is an exception to the rule: a tax expenditure.

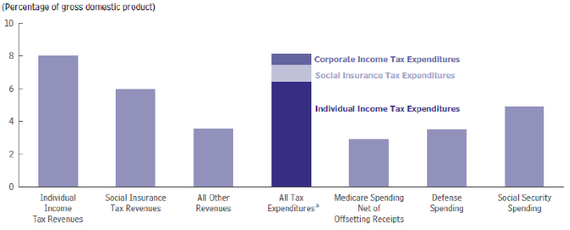

When you stack up all the exceptions carved into our tax structure—the health care exclusion, the mortgage interest deduction, the lower rate on capital-gains income, and more—you have a pile of money taller than any other program in the government budget.

Big Tax Spender

What's the matter with this enormous pile of money? Maybe nothing. The tax expenditure tower includes programs like the Earned Income Tax Credit, which has done wonders to reduce poverty for low-income families. But some budget experts worry that this shadow budget has become an unwieldy excuse for politicians to sneak in new spending programs without using the word spending .

In fact, there's new evidence that Americans are much more likely to accept a new government program if it's described as a "tax break" rather than "spending", even when the programs are identical. Yale Law School students Conor Clarke, a former Atlantic staff editor, and Edward G. Fox , ran a series of online survey experiments that asked people what they thought of various spending proposals. The only variable they changed was whether the proposal was framed as a tax break or direct spending. Consider how you'd respond to the following questions:

- "Would you support the government offering annual $1000 cash payments to each family, to help cover rent?"

- "Would you support reducing each family's taxes by $1000 to help cover rent? If a family owes less than $1000, they get the rest in cash."

These two plans are identical. But respondents didn't see it that way.

People were 10 percentage points more likely to support policies expressed in tax terms. They were also more likely to say that a $6 billion direct subsidy added "a lot" to the federal deficit than an identical $6 billion dollar tax break. It didn't matter how much additional information the researchers provided (in some instances, they clarified that a $1000 refundable tax credit means: you get $1,000 ). People just liked the idea of a tax expenditure more.

In the early 1980s, Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman popularized the idea of "framing effects," demonstrating that people are more likely to support a drug that saves one-third of a group of mortally ill patients than a drug that will kill two-thirds of them. Just as those subjects supported a drug with positive framing ( think of the lives you'll save... ), Clarke and Fox's respondents seem enamored by policies that emphasized savings over new spending.

These days, it's en vogue to consider the American electorate to be clueless glob of near-random, hyper-emotional convictions. Academics have shared this opinion of the country for some time. In 1960, researchers from the University of Michigan published a famous study noting “the general impoverishment of political thought in a large proportion of the electorate,” adding that “many people know the existence of few if any of the major issues of policy.” Clarke and Fox's work is more subtle. The fact that people can have starkly different support for identical programs with slightly different descriptions suggests that even well-intentioned and well-informed voters have a hard time escaping the pull of positive framing effects.

The effects add up, too. The tax-expenditure budget unwinds some of the progressivity of the tax code. More than 50 percent of the benefits of tax expenditures go to the richest fifth of the population, thanks to tax breaks on investment income, savings, and mortgage interest. The richest fifth of the country sees almost all (93 percent) of the benefit of the tax break on capital gains, and the richest 1 percent enjoys two-thirds of that benefit. Something tells me that if the capital gains tax were framed like that, it wouldn't be considered quite so untouchable.