Brad Carson Sgt. Antony S. Lee/Army

The Pentagon Says This Man Can Fix Its Broken Personnel System

Army Under Secretary and former Congressman Brad Carson takes the reins in an office that has seen nine leaders since 2009.

It’s not the highest-profile office within the Pentagon but it has outsized influence on the nearly 3 million troops who serve. It’s the Office of Personnel and Readiness, or P&R, which oversees everything from pay and compensation to housing, healthcare, education and military supermarkets.

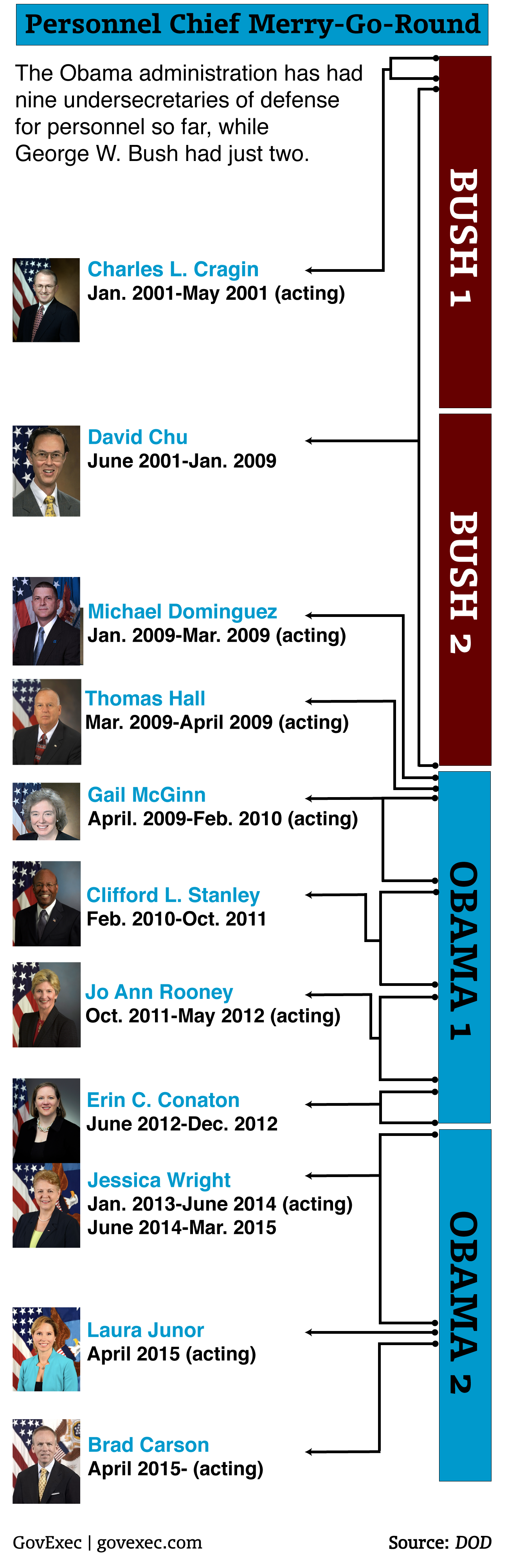

But for the last six years, the office has seen its leaders come and go rather quickly, contributing to a perception in and outside the Pentagon that the office has not been effective in taking care of what senior leaders often call the military’s most precious resource: its people. Not since David S.C. Chu served as personnel under secretary from 2001 to 2009 has the office had any meaningful continuity in its top job. Chu served longer than his nine successors—combined.

The office’s turnover reflects broader problems that have created the perception that it is a graveyard for innovative thinking. “For that office, it seemed the status quo was satisfactory,” former Defense Secretary Robert Gates wrote in his memoir, “Duty,” published last year. “Virtually every issue I wanted to tackle with regard to health affairs… wounded warriors and disability evaluations encountered active opposition, passive resistance, or just plain bureaucratic obduracy from P&R. It makes me angry even now.”

There’s little choice but for Pentagon leaders to work to return the office to its previous stature. The department is considering a major shift in the way it compensates military personnel for their service, in everything from housing allowances to benefits, special pays, and how military careers are structured. But there has been little confidence that the P&R office can drive all these needed changes with so much turnover at the top and, to some extent, so much hardened bureaucracy underneath.

“We have a compensation system that is stuck in the 1950s, but we’ve got a 21st-century military,” said Todd Harrison, senior fellow at the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments. The job of the P&R office, he said, is to adapt compensation and personnel systems to the military of today. But that hasn’t happened. “I haven’t seen a lot of innovative ideas coming out of Personnel and Readiness lately,” he said.

Enter Brad Carson, a former Democratic member of Congress from Oklahoma who has held key positions in the U.S. Army, including as undersecretary of the service, until he was appointed as acting undersecretary for the P&R office this month. Carson is taking over just as the Pentagon grapples with shrinking budgets and this increasingly front-burner need to reform its personnel system.

In an interview with Defense One, Carson said he is looking forward to the challenges and believes P&R can help shape the force for decades to come. But the system has to be more flexible than it is now, and that will require change.

“This is a huge moment in the Defense Department where people are seriously thinking about what the force will look like 10 or 15 years from now,” Carson said. “They are getting their heads above the hurly-burly of 15 years of war… [to see how to create] a flexible personnel system that meets the needs of millennials.”

Carson’s selection stems in part from the degree to which Defense Secretary Ash Carter is focused on some of the internal issues at the Pentagon. Late last month, Carter spoke at his old high school near Philadelphia, and described changes he’d like to make to military enlistments and how he wants to create the “force of the future.” Almost all of that will hinge on P&R’s ability to manage – and sell – those reforms not only to Congress, but to veterans and even service members themselves.

Reforms include modernizing retirement pay, considering changes to career progression and even changing enlistment standards in part to create a new “cyber force” to combat such threats. At the same time, a Congressionally-mandated Military Compensation Reform Commission just outlined earlier this year several changes to compensation and benefits.

“In the coming years, as the so-called 9/11 generation begins to leave our ranks, the Defense Department must continue to bring in talented Americans from your generation and others,” Carter said at Abington Senior High School in Abington, Pa., on March 30. “That starts with being honest about our challenges in attracting people we need and want.”

Some of the changes Carter wants to make will require Congressional action, but others will not. To do any of it, Carter has turned to Carson, who became the Army’s top lawyer in 2011 and then was promoted to Army undersecretary, the service’s second-highest ranking civilian.

The Pentagon will face an uphill battle on some reforms as it confronts entrenched interest groups who believe that any reform is a bad deal for troops or retirees. Other groups are open to changes as long as they make sense for their constituents. In the interview, Carson said that “we won’t break faith” with the people the office serves and “their concerns are my concerns.”

The Military Officers Association of America is one of many groups that have a keen interest in making sure inevitable changes are equitable. Jonathan Withington, spokesman for the group, said MOAA is hopeful about the role Carson can play.

“While MOAA does not endorse or oppose specific candidates for appointed office, we believe Under Secretary of the Army Carson is certainly fully qualified for appointment to the extremely important position of Undersecretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness,” Withington said in an emailed statement.

Carson will have his work cut out for him. Many of P&R’s 32,000 employees feel bitter, alienated and under-appreciated, according to individuals familiar with the office. Those sentiments largely stem from the number of leaders who have cycled through P&R. Since Chu left in January 2009, there have been no fewer than nine acting or confirmed undersecretaries or defacto office heads.

After Chu resigned in the first days of the Obama administration, his deputy, Michael Dominguez, served as acting undersecretary for two months, followed by a month’s service by Thomas Hall. In April 2009, Gail McGinn took over the department, again in an acting capacity.

In February 2010, Clifford Stanley, a retired Marine three-star general, assumed leadership of the office. Stanley was charged with beginning to reform the department – and that meant relieving or firing a number of top officials. But Pentagon officials and former employees of the department said that he alienated many inside the personnel directorate to the point of drawing several inspector general investigations. By October 2011, he had resigned.

Stanley was succeeded by Jo Ann Rooney, who was followed by Erin Conaton, former undersecretary of the Air Force, in June 2012. Conaton, whom numerous employees said was regularly absent from the job, resigned in December of that year citing a “personal health issue.” She was followed by Jessica Wright, who announced her retirement earlier this year.

Last month, the Pentagon threw Wright a large ceremony and bid her adieu. In yet another sign of the confusion in and around the P&R department, the Pentagon announced that a top civilian in that department, Laura Junor, would remain there as principal deputy undersecretary. But in a move that surprised even those close to P&R, Carson was named acting undersecretary a week later.

The impact of the constant turnover within the P&R Department is hard to measure. But officials in and outside of the Pentagon tell stories of how other departments have had to pick up the slack. In just one case of P&R work being farmed out around the Pentagon, a critical review of the military’s compensation and commissary system was handed off to the Joint StaffThat, according to defense officials and others who spoke anonymously for this story, spoke volumes about the caliber of the work being done inside P&R.

The problems at P&R are not only the result of leadership turnover. Like many Defense Department directorates, P&R is comprised of deputies, mid-level managers and thousands of civil servants. In some cases, jobs have been filled with people who are not considered qualified to hold them, according to defense officials. Some believe that any attempts to update the military compensation system, for example, or make other changes, will require new thinking and, to some extent, new and competent people inside P&R.

Still, the constant turnover at the top has not helped. In one case, according to Scott Amey, general counsel for the Project on Government Oversight, or POGO, who was advocating for the Pentagon to find cheaper alternatives to hiring contractors, it became impossible for P&R to seize the initiative. Amey’s organization had conducted an analysis that showed that hiring government workers instead of contract employees could save the Pentagon tens of millions of dollars. He said he became frustrated that no one in P&R seemed interested in the issue. Much of that was due to the fact that it seemed as if no one was home at the top.

“This constant turnover ends up with a component of the Department of Defense that is kind of blowing in the wind,” said Amey.

Carson said he recognizes that the people who work within P&R have seen a number of leaders over the years, and that each new leader came and went for different reasons. For his part, he said he strives to be a leader worthy of those employees’ commitment to the job. “I think the people who work in P&R are some of the most committed and excellent workforce in the [Defense Department]” he said. “They really are the heart of the Department of Defense.”

If history is any guide, Carson has just 21 months to make his mark before a new administration takes office in January 2016.