Architect of the Capitol

Reports of the Death of Congressional Oversight Are Greatly Exaggerated

Congress wanted an aide to President Trump to testify; Trump ordered him not to. Congress went to court over it, and the court told both sides to leave the courts out of it and negotiate a solution.

For over 200 years, Congress and the executive branch have maintained a delicate balance of power. When disputes between the two branches have arisen, they have compromised and turned to the courts only as a last resort.

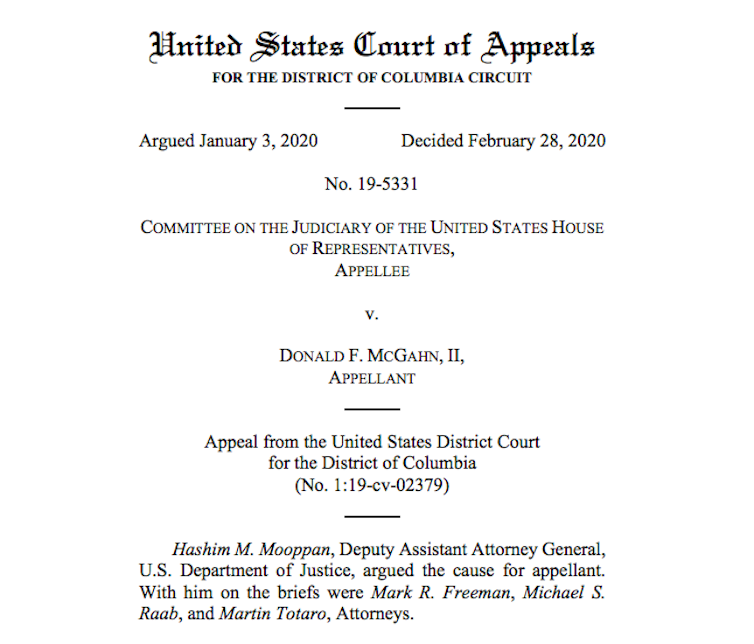

Recently, an appeals court ruled in House Committee on the Judiciary v. McGahn that courts do not have authority to enforce congressional subpoenas. In this case, it was a subpoena for a former White House legal counsel to testify before a congressional committee.

Political commentators and scholars immediately decried the opinion as eviscerating Congress’ oversight powers. The opinion was seen as so potentially harmful that the House Judiciary Committee asked the court to reconsider the case, and the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit will do so in late April.

A close look at the decision suggests the court may be trying to restore the balance of power by reminding the political branches that the Constitution expects them to cooperate with one another. Short of that, the decision said, Congress has the power to enforce its own subpoenas.

‘Absolute immunity’

In the McGahn case, the House Judiciary Committee subpoenaed former White House Counsel Don McGahn in May 2019 as part of its inquiry into whether President Donald Trump obstructed justice during the Mueller investigation.

Trump instructed McGahn not to testify, asserting that presidential advisers possess “absolute immunity” from congressional subpoenas. McGahn obeyed the president’s order, and the House Judiciary Committee sought court enforcement of its subpoena. The district court ordered that McGahn comply with the subpoena, and the Trump administration appealed.

Rather than involve itself in the dispute, the D.C. Circuit’s majority opinion followed earlier cases encouraging the political branches to negotiate and accommodate. It lamented the recent breakdown in the time-honored process of negotiation and accommodation, noting that “the branches never brought these kinds of suits” until the 1970s.

Refusing to decide such cases now, the majority emphasized the constitutional duty of the political branches to negotiate and accommodate.

In short, it told the political branches to get their acts together and go back to the negotiating table.

Congress’ turn

The court’s message to Congress was clear: Congress should use the many oversight tools it has “to turn up the heat” on the executive branch.

Insisting that it was not leaving Congress without recourse by refusing to enforce the subpoena, the court majority enumerated the many ways that Congress could encourage the executive branch to engage in negotiations.

Congress “may hold officers in contempt, withhold appropriations, refuse to confirm the President’s nominees, harness public opinion, or delay or derail the President’s legislative agenda, or impeach recalcitrant officers,” Judge Thomas B. Griffith wrote.

In short, the court wasn’t undermining Congress’ oversight powers; it was urging Congress to use them.

As at least one commentator has noted, if Congress were to heed the court’s advice and more aggressively use the oversight tools it has, it would “empower Congress rather than weaken it.”

Arrests by Congress rare

Congress’ hesitation to call in the sergeant-at-arms to detain recalcitrant executive branch officials most likely reflects the seriousness of such action. Turning to the courts appeared more decorous and less aggressive than arresting administration officials.

The courts had upheld congressional subpoenas to the executive branch in the past, so the House Judiciary Committee had good reason to pursue legal enforcement against McGahn.

But even though the courts have affirmed Congress’ authority to detain individuals for refusing to comply with congressional demands for information, Congress has rarely resorted to detaining people. It has not detained anyone since the 1930s, preferring to negotiate and accommodate to resolve disputes over information with the executive branch.

Yet American politics have shifted dramatically during the Trump administration. The tacit agreement between the political branches to negotiate and accommodate has disintegrated.

The president has categorically refused to cooperate with Congress. His disregard for Congress led him to argue that the impeachment proceedings were unconstitutional.

In this new political reality, Congress may have no choice but to protect its oversight powers by forcefully reasserting them.

Not everything resolved

The court sent a message to the president as well.

The court did not – as the president had wanted – affirm that presidential advisers have absolute immunity. In fact, a majority of the three-judge panel expressed grave skepticism about such claims by the president.

One of the judges in the majority wrote separately to cast considerable doubt on that claim, noting that the Trump administration had identified “no case law recognizing the existence of such immunity from congressional process.”

Contrary to the recent alarmist response that Congress could no longer hold the president accountable, the decision in McGahn was not an unequivocal victory for either side. It was a reminder, instead, that they have constitutional obligations to work together. Whatever the D.C. Circuit decides when it rehears the case in late April, that point – that the legislative and executive branches have that obligation to work together – will not change.

![]()

This post originally appeared at The Conversation. Follow @ConversationUS on Twitter.