State Department

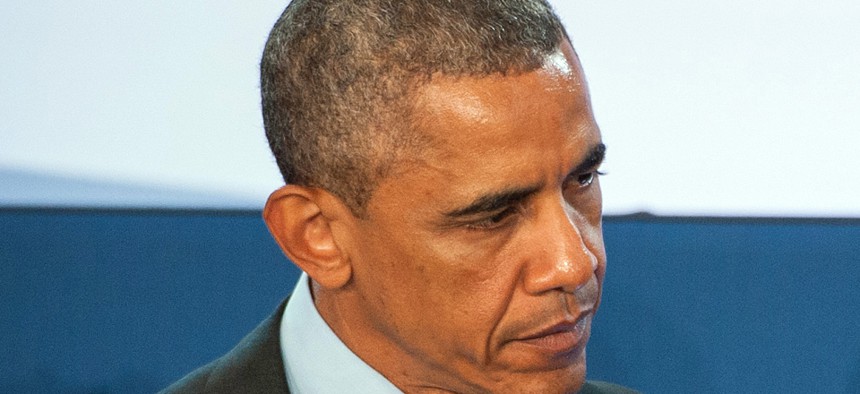

How Awful Will the Midterms be for the Democrats?

Midterm elections come in three varieties for the White House party: bad, really bad, and horrific.

In bad midterm-election years, members of a president's party often find the political climate challenging. In some ways, it is like a swimmer encountering riptides or facing strong undertows. The degree of the danger varies from location to location, and in many cases, weak swimmers struggle in this environment; occasionally, even an Olympic-level swimmer perishes.

In 2010—President Obama's first midterm election—Democratic congressional candidates struggled mightily. The party suffered a net loss of six Senate seats and 63 seats in the House. That was the worst loss for either party in any election since 1948, and the largest loss in a midterm election since 1938. Fallout from the health care debate and the Affordable Care Act contributed heavily to Democratic losses, but that legislation was hardly the sole reason for them.

The shoe was on the other foot in 2006—President Bush's second midterm election—when, between an increasingly unpopular war in Iraq and the administration's mishandling of the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, the election was a total horror show for GOP candidates. It was like watching a car wreck in slow motion. I vividly remember conversations with key GOP campaign committee strategists who began the cycle confident that their ample war chests would insulate their vulnerable candidates through a difficult election. But as Bush's and the Republican Party's problems mounted, their financial advantage was less and less comforting, and these top campaign pros became increasingly worried.

I also recall, in late 2005, I believe, over a steak dinner and good wine—it works well for building and lubricating relationships, plus is admittedly a lot of fun—a pair of House Republican pros nonchalantly asking me about how the 1994 Democratic debacle unfolded. The question came across as, "What did you see and when did you see it?"

These two seemed curious to know what the leading indicators were that the bottom was about to fall out for Democrats during President Clinton's first midterm election. This was the year when "Hillarycare" and tax increases became quicksand for the party's candidates in every corner of the country, but particularly in the South and the border South—small-town, rural, and suburban districts alike (pretty much everywhere but urban districts).

I told them the spring 1994 story about David Dixon, the then-political director of the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee, who, after we had done a 50-state, off-the-record rundown of every competitive House race, casually asked me if I had noticed anything unusual in House contests over the past month or so. After I indicated I had not, Dixon mentioned that he had seen some unusual polling patterns over the previous month or two—specifically, the levels of support for Democratic incumbents whom one might expect to be in the mid- or high-50s (poll numbers looked different in those days) that were coming in just barely above 50. Dixon went on to explain that there were others you might expect to be at about 50 percent approval who were polling in the mid-40s. He suggested that there was a pattern of underperforming Democratic candidates in a wide variety of regions and types of districts.

At the time, I thought the very able Dixon and his equally impressive DCCC chairman, Vic Fazio, were lowballing, trying to bring down expectations so they would look good on election night. But, over the next month or so, my instincts—perhaps sensitized by Dixon's observation—began to pick up the same pattern.

As we got to late summer and early fall in 1994, it became clear that a wave was building, a big Republican wave, but it still looked unlikely that the GOP would score the 40-seat net gain needed to win a majority for the first time in 40 years. Giving Republicans every conceivable competitive race, you still couldn't count 40 Democratic losses.

On election night, the GOP picked up a mind-boggling 54 seats, winning districts that had never received a dime from the national party; long shots who had seemed to be jokes were actually winning.

Now, back at the Capital Grille dinner table in 2005, as I was relaying this story from the 1994 election, the National Republican Congressional Committee guys were listening intently, clearly trying not to show concern but wondering whether the signs from 1994 on the Democratic side were being replicated on the GOP side a dozen years later.

Not every midterm election unfolds like 1994, 2006, or 2010. In 1998, a backlash against the impeachment of Clinton resulted in Democrats escaping the typical midterm election jinx. In 2002, not even 14 months after September 11, the reverberations of tragedy insulated Republicans from the normal losses they might have suffered. These examples are the exceptions that prove the rule; the normal pattern is that midterm elections come in three varieties for the White House party: bad, really bad, and horrific.

Candidates in safe districts have little to worry about. They may or may not see a few points knocked off their typical election night performance. Others will have much closer margins than usual but will still win. Still others will barely survive, and some won't. It depends on the situation in the state or district; the strength of the candidates in the president's party; the quality of the opponent; the circumstances that year; and even luck. These factors are what Democrats have to be considering now.

This article appears in the September 13, 2014 edition of National Journal Magazine as How Awful Will It Be?.