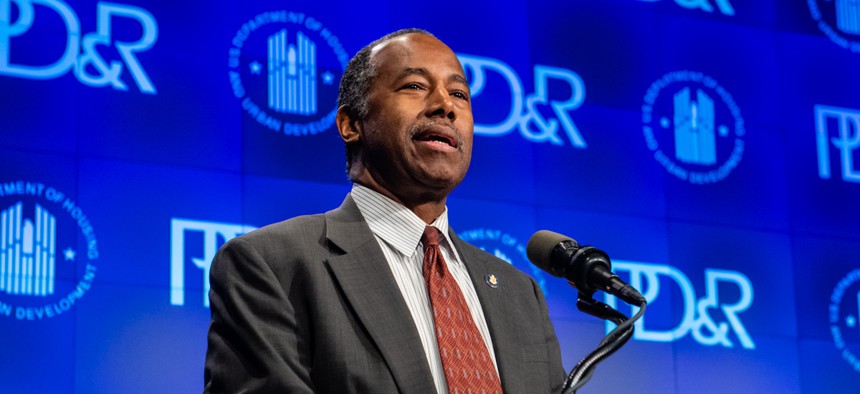

HUD file photo

Why HUD Wants to Restrict Assistance for Immigrants

A proposal by Ben Carson’s agency would eject immigrant families from public housing to make way for the "most vulnerable." Housing advocates aren't buying it.

The Trump administration is targeting immigrants with a new policy—this time, by seeking to restrict housing assistance for families with mixed-citizenship status.

On Wednesday, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) proposed a new rule that seeks to vet all members of families applying for subsidized or public housing, even those who have declared themselves ineligible in the application. According to the administration, this rule, if promulgated, would help cut down the years-long waitlist for public assistance.

But housing advocates say that it would have little to no effect on the factors that prevent millions of eligible households from finding public housing or rental assistance.

“Thanks to [President Donald Trump’s] leadership, we are putting America's most vulnerable first,” HUD Secretary Ben Carson tweeted in response to a story from the Daily Caller on the proposed rule. “Our nation faces affordable housing challenges and hundreds of thousands of citizens are waiting for many years on waitlists to get housing assistance.”

To achieve this, Carson has proposed a policy that the department claims would eject some 32,000 families from federal housing programs, including public housing, Project Based Rental Assistance, and the Housing Choice Vouchers program (traditionally known as Section 8).

But housing experts aren’t persuaded by the federal housing administration’s math. The National Low Income Housing Coalition estimates that the number of households that contain family members who are not eligible for aid is smaller: between 22,000 and 25,000 households, most of them located in New York, Texas, and California. This figure might comprise 32,000 affected individuals, many or most of whom might in fact be eligible for aid.

Housing advocates also question whether this policy would make any real dent in waiting lists that, across the U.S., are millions of names long, collectively. Instead, they say, it would simply impose another penalty on immigrants.

“HUD falsely claims the change is proposed out of concern for long waiting lists, when they know well that it would do nothing to free up new units," says Diane Yentel, president and CEO of the National Low Income Housing Coalition. "The true purpose may be part of this administration’s effort to instill fear in immigrants throughout the country."

Currently, HUD allows families to live together in subsidized housing even if one member of the family is an ineligible immigrant. The agency prorates the subsidy for the household, so any family members who declare that they are not eligible are simply excluded from the benefits. Only certain types of non-citizens are permitted to receive housing assistance, per a 1980 law. And HUD vets the immigration status of eligible applicants, but the department does not track the ones who are not claiming benefits. A person can be ineligible for reasons other than immigration status.

The new policy would change that rule so that even one undocumented family member becomes a poison pill that prevents the whole family from living in subsidized housing, even if the ineligible individual is not claiming or receiving any benefits themselves.

“So essentially, what HUD is saying is that, say, the mom is undocumented, but she’s got five kids who are citizens, then this is going to make those kids homeless,” said Judith Goldiner, attorney-in-charge of the Civil Law Reform Unit of The Legal Aid Society in New York. That mom would also be vetted if she applied for housing for her kids, meaning HUD would learn her immigration status.

According to HUD, 32,000 households it assists are headed by “not-legal U.S. residents.” Housing and immigration policy experts are not sure how the agency got this number. It is not clear, for example, if it includes non-citizens who are eligible for housing assistance, such as certain victims of domestic violence who are legally present in the country. (HUD did not respond to questions about how it calculated this estimate.)

Housing experts also don’t buy the claim that this proposal would drastically change the length of the waitlists for people around the country seeking housing assistance. HUD’s suggested point of reference—those 32,000 HUD-assisted households—is dwarfed by the total number of people currently on these waitlists. A study conducted by the National Low Income Housing Coalition identified approximately 1.6 million families on waitlists for public housing and more than 2.8 million families on waitlists for the Housing Choice Voucher program (also known as Section 8).

“Unfortunately, 32,000 is a lot of people to become homeless, but not a lot of people to be taken off waitlists,” Goldinger said. Just in New York City, 209,180 people were in line to get a spot in public housing and 148,000 were waiting for Section 8 vouchers, she adds. “What’s really needed is housing for people, and not shifting deck chairs.”

But Trump’s policy agenda is otherwise tailored to limit housing assistance—not expand it. The Trump administration has sought to slash spending on welfare and impose restrictive work requirements for those who receive assistance for food, healthcare, and housing. Congress has not passed the austerity budget envisioned by the White House. The White House has nevertheless put its stamp on housing policy in other ways. Carson rolled back a fair housing rule years in the making. He also announced last June that the department will revisit its rule on the legal doctrine known as “disparate impact,”the prohibition on policies that discriminate on the basis of race without doing so explicitly.

Immigrant advocates and other organizers also see HUD’s move as the latest in a suite of policies to cut down the number of working-class immigrants trying to immigrate to the country, even through legal pipelines—and to make life a little bit harder for the mixed-status families who are already here.

“This is really a broader story about how the long-term cost of President Trump's whimsical immigration policies—here masked under a proposed HUD regulation—will be borne largely by the nearly six million U.S. citizen children that live in a mixed-status household,” said Carlos Guevara, a senior policy advisor at Unidos, an organization that works with 300 local organizations in Hispanic communities.

In 2018, DHS proposed a rule limiting individuals from advancing on the path to citizenship if they are deemed likely to become “public charges.” That is, if the agency decides that an applicant will likely use an array of public benefits, including Section 8 vouchers and other housing subsidies, it can deny them a green card. The non-partisan Migration Policy Institute estimated in November that 6.8 million people may stop seeking benefits they need and are eligible for out of confusion and fear. DHS itself noted that the public charge rule could have several “downstream and upstream impacts on state and local economies, large and small businesses, and individuals.” (The State Department and DHS’s U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services have also toughened vetting and are already seeing the effect.)

The tone of the Trump administration’s immigration agenda may also be indirectly affecting housing. Shortly after his inauguration, housing advocates and attorneys in California reported an uptick in complaints about landlords threatening to report or evict tenants to immigration authorities.

The HUD rule is currently being reviewed by Congress. Notice will appear in the Federal Register in 15 days, and the rule will still have to go through the obligatory 60-day notice-and-comment period during which it will receive public feedback. Even before all that though, it could start having a “chilling effect” like these other rules.

“All of these policies work in tandem with each other. There is an agenda to go after immigrant families,” says Karlo Ng, supervising attorney for the National Housing Law Project. “Naturalized immigrants are already asking advocates, is this going to affect me? And of course it does not affect naturalized citizens. There’s a lot of confusion.”