How Ex-Congressman Jeff Miller Is Single-Handedly Shaping The Push To Privatize VA Health Care

Behind Miller’s growing lobbying portfolio lies one of the biggest unexamined shifts in Washington’s influence game.

This story was produced by Reveal from The Center for Investigative Reporting, a nonprofit news organization. Get their investigations emailed to you directly by signing up at revealnews.org/newsletter.

The Indian Treaty Room is a grand two-story meeting space in the Eisenhower Executive Office Building next to the White House, with French and Italian marble wall panels, a pattern of stars on the ceiling and the image of a compass worked into the tiled floor. Over the years, it has hosted signing ceremonies for historic foreign policy pacts such as the Bretton Woods agreement and the United Nations Charter.

On Nov. 16, 2017, it hosted a different kind of gathering: an intimate meeting called by the White House to discuss the future of the Department of Veterans Affairs. In the 10 months since Donald Trump had taken office, his administration had been pushing a bold and controversial agenda to privatize more of the VA’s services.

The Trump administration’s ambitions are well documented. But what has not been publicly revealed until now is the extent to which the VA – a sprawling agency with a $180 billion annual budget that includes the nation’s single largest health care system, a network of cemeteries and a massive bureaucracy that administers the GI Bill and disability compensation for wounded veterans – has become a massive feeding trough for the lobbying industry.

The VA’s then secretary, David Shulkin, was at the previously undisclosed meeting, along with a contingent of conservative thinkers on veterans policy, including current and former members of Concerned Veterans for America, known as CVA, an advocacy network largely backed by conservative donors Charles and David Koch. Also present were “Fox & Friends” host Pete Hegseth, a former CVA executive repeatedly floated to be Trump’s pick for VA secretary, and David Urban, a right-leaning CNN commentator who served as a senior adviser on the Trump campaign.

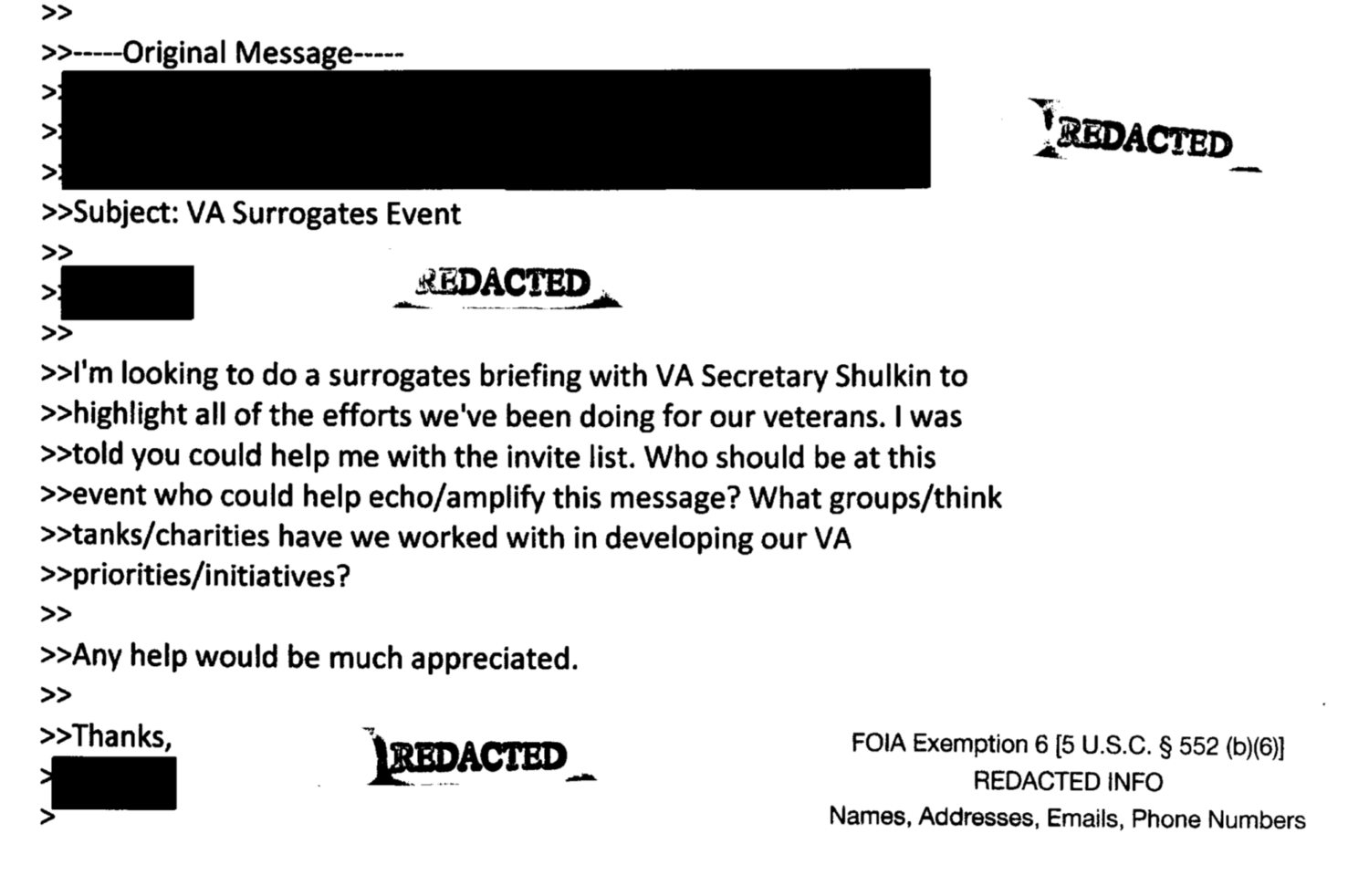

According to emails obtained under the Freedom of Information Act, the group drafted a strategy to “echo/amplify” Trump’s “priorities/initiatives” for accelerating the privatization process. According to three people who were there, the participants discussed how best to respond to expected resistance from traditional veterans advocates, who historically have opposed privatizing key agency services. Representatives from “the Big Six” major veterans organizations, including the American Legion and Veterans for Foreign Wars, were not invited.

But it was the presence of the most powerful lobbyist for the companies now trying to get a piece of the VA’s budget – a tan, affable Floridian named Jeff Miller – that would have raised the most eyebrows, had his attendance been known at the time.

Until January 2017, Miller, 59, had been a member of Congress from the Panhandle and the head of the powerful House Veterans’ Affairs Committee, which oversees the VA and produces legislation affecting veterans’ lives. In 2014, as committee chairman, Miller helped draft the Veterans Access, Choice and Accountability Act, the law that first embraced wide-scale funding of private-sector health care for veterans. Since President Barack Obama signed the law in August 2014, millions of appointments have been made in the private sector – a monumental change in veterans’ health care delivery that has brought billions in new revenue for health care companies and created an opening for them to pitch their services as an attractive alternative to government care.

Within months of leaving office, Miller registered as a corporate lobbyist and joined McDermott Will & Emery, a white-shoe lobbying firm located a half-mile from the Capitol. By the time the meeting in the Indian Treaty Room took place, Miller had three clients vying for access to veteran patients and VA dollars. He subsequently would lobby on behalf of seven other private interests seeking a piece of the agency’s budget.

Reveal from The Center for Investigative Reporting’s analysis of publicly available federal lobbying reports found that 20 years ago, fewer than two dozen corporate interests lobbied the agency. But as the VA system strained under the weight of returnees from the Iraq and Afghanistan wars, private interests saw an opportunity. By 2013, 146 companies disclosed that they lobbied the VA, and the next year, when the Choice Act was passed, that number jumped to 203. In 2018, the year after Trump took office and Miller entered the lobbying force, it was 230.

Reveal’s lobbying analysis found Miller has facilitated a gravy train of government largesse to his clients – a list that includes a disgraced hedge fund magnate pushing unproven treatments for post-traumatic stress disorder and a trade group for proton beam therapy, an expensive radiation application. Miller also lobbied on behalf of a troubled disability evaluation company as it secured a $205 million contract to evaluate veterans’ benefits claims. Miller also has represented major players in the VA contracting space, such as medical records firm Cerner, which in May signed a $10 billion contract with the VA. Last week, Miller signed on to represent Salesforce, the cloud computing giant, which a lobbying disclosure states seeks “access to customer relationship management (CRM) platform” at the agency.

As the VA has become an increasingly attractive target for corporate lobbying, Miller has emerged as a one-man gatekeeping operation. Although he has no military experience, the former television weatherman was an early backer of Trump’s campaign – which, with his former committee chairmanship, gives him close ties to Congress, the agency and the administration.

“He has the cell numbers of a great many members of Congress and VA officials, many of whom are deep personal friends,” said Jim Moran, a former Democratic lawmaker from Virginia and McDermott lobbyist who often works alongside Miller.

To critics, Miller’s new role makes him an almost uniquely egregious example of the revolving door between Congress and private-sector lobbying firms – one that appears to be as fast-moving as ever, despite the president’s pledges to “drain the swamp.” As the head of the House Veterans’ Affairs Committee, Miller helped write the very privatization legislation that opened the door to his lobbying operation. As an early Trump backer and a name repeatedly floated as a potential VA secretary, Miller personally shaped the president’s policy; he drafted the Trump campaign’s 10-point veterans policy paper, largely based on proposals he was unable to pass in his time on the Hill. (Moran said Miller also has communicated directly with Trump “on occasion” since joining McDermott.)

And when it comes to Miller’s contacts with the VA, the lobbying is also an example of an unusual loophole: Although current lobbying rules would forbid Miller to lobby Congress directly in his first year out of office, he’s still allowed to lobby the VA, which is part of the executive branch. While Miller was banned from meeting with former colleagues or their staff, he faced no restrictions on crafting veterans policy from the shadows. This loophole allowed Miller to freely wield influence from the White House grounds.

Miller did not respond to multiple email messages and telephone inquiries. His lobbying partner, Moran, declined to discuss his clients.

Veterans advocates said Miller’s quick embrace of corporate lobbying is unprecedented for a former chairman of the Veterans’ Affairs Committee and voiced alarm at the development.

“It’s a bad precedent, in some ways the worst of what Washington can be,” said Paul Rieckhoff, founder of Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans of America. “If you can so quickly go from committee chairman to hired gun, it’s not good for democracy, and it’s not good for veterans.”

The story of Miller’s rapid trip through the revolving door is a striking illustration of just how loopholes, laws and outside interests come together in modern Washington – and the astonishing speed at which the VA, in particular, is being remade from a century-old public-service backwater into a bonanza for private industry and corporate spending.

“Miller sees a huge money opportunity,” said Shad Meshad, a Vietnam veteran and former combat medic who heads the National Veterans Foundation.

“Look, there are issues inside the VA that need to be addressed,” said Meshad, who like many other veterans advocates sees Miller’s lobbying work as an extension of his work in Congress to privatize the agency. “But I’m really against handing everything over to private interests. There’s no accountability. For them, it’s often about money, not about the veteran.”

***

Jeff Miller grew up in Chumuckla, Florida, a farming community in the western corner of the state’s Panhandle with less than 1,000 residents. He took a number of disparate jobs – disc jockey, deputy sheriff, aide to the state’s Democratic agriculture commissioner – before he won a 2001 special election to replace Joe Scarborough, now an MSNBC host, according to a Tampa Bay Times profile. While Miller has no record of military service, his old congressional district, which includes a sprawling naval air station, claims 109,000 veterans, more than almost any other in the country.

Miller’s office in the Cannon House Office Building featured many of the typical trappings of any lawmaker’s quarters: photos with constituents and colleagues, plush chairs, an American flag. They also were mounted with the taxidermied heads of animals he bagged in the wild, including birds, and a Red Ryder BB gun.

He had a largely low-key congressional career until the spring of 2014, when he jolted Congress and attracted the nation’s attention by spotlighting issues at a VA hospital in Phoenix, where administrators allegedly cooked the books to obscure long wait times for patients at the overloaded center.

From his chairman’s perch on the House Veterans’ Affairs Committee and in frequent cable news interviews, Miller said he was investigating as many as 40 deaths stemming from delayed care in Phoenix. Furthermore, he cast the facility’s troubles as a symptom of endemic problems inside the VA. Then-VA Secretary Eric Shinseki resigned, and the pressure created momentum for the passage of the VA Choice Act.

Miller’s aggressive approach toward the agency on his congressional committee earned him both praise and recrimination. For years, advocates had been complaining that the agency’s budget and staffing levels were insufficient to handle the flood of recently returned veterans, as well as the complex and expensive needs of aging Vietnam veterans. Miller’s work put these problems in the political spotlight, and a number of veteran organizations applauded Miller’s investigative efforts uncovering deficiencies at the agency. In 2014, the American Legion presented Miller with its Patriot Award for “providing needed oversight and attention to make (the VA) a system truly worth saving.”

Other VA officials, veterans advocates and Capitol Hill staffers, however, told Reveal that they saw Miller as too political, with some calling his campaign a thinly veiled effort to embarrass the Obama administration, denigrate the public image of the agency and its leaders, and set the stage for corporate players eager to peel off VA patients. Former VA Secretary Bob McDonald, who took the reins from Shinseki to clean up the agency’s problems, once quipped that he likely would become the next head mounted on Miller’s wall.

“Lots of good got done on Miller’s watch,” said Carl Blake, executive director of Paralyzed Veterans of America. “At the same time, I’m not sure all the oversight was aimed at improving the VA so much as scoring political points.”

Rep. Jeff Miller (left), R-Fla. – shown with then-Senate Veterans’ Affairs Committee Chairman Sen. Bernie Sanders, I-Vt., in 2014 – attracted the nation’s attention by spotlighting issues at a VA hospital in Phoenix. Administrators allegedly cooked the books to obscure long wait times for patients at the overloaded center. Credit: J. Scott Applewhite/Associated Press

Delaney Marsco, ethics counsel at the Campaign Legal Center, said that in practice, the congressional cooling-off period “doesn’t prevent the exertion of all types of influence” and “only slightly slows the revolving door.” While Marsco couldn’t say how common the exploitation of this loophole is among former lawmakers, she derided the practice as “a bad look for democracy.”

“The logic with this background loophole is that lawmakers won’t be aware of a former member’s role driving an action, so the potential for a corrupt influence isn’t really there,” she said. “But often, the behind-the-scenes work and information a former member of Congress can provide is very valuable. They know the procedures, who to talk to, how the system works. They provide a valuable leg up to a special interest.”

According to former VA officials, in the months after registering as a lobbyist, Miller worked to build connections with top VA officials – including Secretary David Shulkin – through frequent emails, phone calls and LinkedIn requests. (In addition to attending Miller’s congressional going-away party, Shulkin also was introduced by Miller at a legal forum on veterans’ issues at McDermott’s Washington office.) Three former VA officials said Miller often reached out to agency leaders on behalf of his clients. They included Gregory Giddens, who retired as executive director of the VA’s acquisition, logistics and construction office in November 2017.

Giddens recalls Miller reaching out to him on behalf of various clients looking to get more contract work. (Oddly enough, in the late 1970s, Miller and Giddens shared a dormitory at Abraham Baldwin Agricultural College, a connection that Giddens said Miller played up.)

“Jeff Miller understands the VA and can work with a company to position them better to submit a proposal to the government,” said Giddens, now working at a private consulting firm. “There’s a lot he could offer a company interested in veterans’ issues.”

Miller’s work kickstarted shortly before the Government Accountability Office identified significant problems with the VA’s acquisition office and added it to its “high-risk list.” In an interview, Shelby Oakley, a director on the GAO’s contracting and national security acquisitions team, said the deficiencies opened up the contracting process to potential “waste, fraud, abuse and mismanagement.”

Giddens said one of Miller’s clients, American Medical Depot, was “off to a rocky start” before the former Congressman came on board, but that “after they got sideways,” Miller “showed them how to get back, straight up.” He was “there to signal that this company was earnestly trying to make a go of it,” Giddens said. With Miller in the company’s corner, American Medical Depot secured a new, $13.5 million contract in December 2018. Giddens also recalls Miller inquiring about the status of contract work at the Denver-area VA hospital, a recently completed building project that Miller, while in Congress, called “the biggest construction failure in VA history.”

Miller’s connections are threaded through the VA: Miller’s former press secretary, Curt Cashour, is now the VA’s spokesman, and his former committee investigator, Tamara Bonzanto, recently was confirmed to run the VA’s controversial Office of Accountability and Whistleblower Protection.

Miller’s first registered client on veterans issues was Steve Cohen, the hedge fund billionaire whose former firm, SAC Capital Advisors, engaged in the largest insider-trading scheme in U.S. history. In 2016, Cohen, then facing a two-year ban on handling other people’s money, launched the Cohen Veterans Network, which furnishes mental health care. He also founded Cohen Veterans Bioscience, which spearheads research into novel treatments and diagnostic tools for post-traumatic stress disorder. Some of Cohen’s research work appears to be duplicating previous VA research that yielded few promising results. Cohen also has partnered with two pharmaceutical companies developing PTSD drugs, including antipsychotic medications and muscle relaxants. The VA and Pentagon clinical guidelines for treating PTSD explicitly caution against using both classes of drugs “due to the lack of strong evidence for their efficacy and/or known adverse effect profiles and associated risks.” Veterans advocates and health care professionals have raised concerns about Cohen’s treatment network, saying it is more expensive, untested and less accountable than the VA.

A report by ProPublica on Cohen’s clinics did not find evidence that Miller himself approached Congress, but reported that Miller’s lobbying team “visited the office of every member of the House veterans committee” in their effort to get the bill passed. A spokesman for Moulton told Reveal that neither the congressman nor any staffers communicated with Miller directly in 2017, when he effectively was banned from congressional lobbying. Gallagher’s spokesman did not respond to Reveal’s questions.

Although the bill died, Miller’s work on behalf of Cohen’s mental health network still yielded results. In February 2018, the VA announced a partnership with the Cohen Veterans Network to “expand and promote community collaboration to increase veterans’ access to mental health resources.” The Cohen Network subsequently secured approval to be a designated Veterans Choice provider, which entitles it to reimbursement from the VA.

***

Jeff Miller’s other clients include Virta Health Corporation, which says it can “reverse type 2 diabetes without medications or surgery”, and Ambrosia Treatment Center, a drug rehabilitation network that recently launched a veterans treatment program.

Also on Miller’s client list is the National Association for Proton Therapy. The trade group promotes a form of cancer treatment that has drawn criticism in the private sector for its high costs and marginal benefits over normal radiation therapy. A VA memo obtained by Reveal, sent to directors of the agency’s 1,250 hospitals and clinics, said that while the treatment potentially could be advantageous for a few clinical applications, its benefits were “generally not supported by current clinical evidence” and advised against its use on veteran patients with a number of conditions. A 2018 review of available research into the therapy noted it “has the potential to reduce toxicities in cancer patients, but is relatively expensive and unproven,” and a January op-ed by two oncologists warned that “for the vast majority of adults with cancer, it is still not clear proton therapy provides benefits.”

Another of Miller’s clients, Veterans Evaluation Services, has been the subject of multiple unflattering reports. It is one of five companies that determines whether veterans are disabled and entitled to compensation and health care benefits. A November report from the Government Accountability Office found that Veterans Evaluation Services and the other four contractors routinely subjected veterans to long wait times and made significant errors in exam reports.

In 2015, the Tampa Bay Times reported that the company sent dozens of veterans to a Tampa doctor who was under federal investigation. The company also has been the target of dozens of troubling allegations on the employer review website Glassdoor, including that the quantity of evaluations is prioritized over quality. Margaret Rajnic, a nurse who worked for Veterans Evaluation Services for six weeks in early 2018, told Reveal that the organization is poorly run and that many of its reviewers had no familiarity with basic medical terms or procedures. Rajnic said she was fired after raising questions over the company’s business practices.

“Their operational efficiency is poor, they are bad at providing necessary medical records, and it’s failing veterans,” she said. “It’s a money-making machine, and the VA is not evaluating the company’s true outcomes.” The company did not respond to a request for comment.

Among Miller’s other clients are recipients of two of the VA’s largest contracts: TriWest Healthcare Alliance and Cerner Government Services, a Kansas City, Missouri-based technology company that caters to the health care industry. Both contracts’ size and scope have been publicly questioned, and the two companies are now in control of key parts of the veterans health care system. Like some of Miller’s smaller clients, both have come under scrutiny for the quality of their work.

Cerner brought on Miller the same day the company signed a $10 billion sole-source contract to modernize the agency’s electronic health records system. Because of the importance of the contract, the firm will be overseen by a special House oversight panel; Miller has been meeting with House and Senate staffers on Cerner’s behalf. According to the Kansas City Business Journal, in late December, the VA canceled an older $624 million contract that would have given a piece of the modernization effort, for patient appointment scheduling, to two other vendors.

Miller also has lobbied for TriWest, which recently secured a contract expansion granting a virtual monopoly over coordination of veteran care in the private sector. The new contract, which is estimated to quadruple TriWest’s revenue, came a month after an inspector general’s report found the company had filed more than 111,000 duplicate claims for outside care to the VA, resulting in more than $45 million in agency overpayments. A federal grand jury currently is investigating whether TriWest “committed wire fraud and misused government funds” in its contract work for the VA. (In 2011, TriWest settled with the Justice Department for $10 million over similar allegations.)

In a statement, TriWest pointed to the inspector general’s report, which found that, among others things, the agency “did not implement effective internal controls to detect the submission of duplicate claims.” TriWest’s latest contract with the VA will expire later this year, and the company now is bidding on a replacement contract offered through the VA Mission Act, which makes the agency’s community care program permanent.

“Mr. Miller has assisted us in understanding legislative intent behind the Mission Act as we work with VA to implement components of the new legislation,” a TriWest spokesman said in a statement.

***

The veterans policymaking arena is unique in that a core group of membership-based veterans service organizations wield incredible – and often unquestioned – sway over VA policy. Having won awards from these groups while in Congress, Jeff Miller has sought buy-in from them on behalf of various clients.

“Anytime Jeff has a client, he advises us of their abilities, their game plan and why they should receive our support. He knows veterans groups are trusted and give input on lots of issues,” said Garry Augustine, the recently retired legislative director for the advocacy group Disabled American Veterans. Like other veterans groups, Disabled American Veterans is opposed to privatization, but because it has worked with Miller in the past, it has been willing to hear him out.

While Miller’s outreach to these interests is frequent, he often has found skeptical veterans on the other side of the table. His Cohen clinic bill, for instance, essentially was killed after veterans advocates castigated it. Moreover, as Trump was considering Miller for VA secretary in 2016, a slew of veterans advocates forcefully advised against it.

Miller is now closest with staffers and alumni of Concerned Veterans for America, a Koch-backed organization whose influence in Trump’s Washington is ascendant. (Former staffer Darin Selnick helped write the VA Mission Act and now is working on its implementation as a senior adviser to VA Secretary Robert Wilkie.) Founded in 2011, the well-heeled group is an arm of Americans for Prosperity, a nonprofit umbrella of free-market advocates created by conservative billionaires Charles and David Koch. According to its most recent available 990 tax form, it has $13 million in the bank, and CVA has in large part eclipsed the influence of membership-based veterans groups such as the American Legion. In 2014, Miller became the first lawmaker to invite CVA to testify before Congress, a move that angered traditional veterans advocates, many of whom see the group as engaging in “AstroTurf advocacy” – fake grassroots campaigns – aimed at privatizing the VA.

CVA has supported Trump’s VA agenda aggressively, including two major agency reforms that came straight from Miller’s mind. Before Trump was inaugurated, Miller served as an ad hoc spokesman on veterans’ issues, telling POLITICO in December 2016 that “Mr. Trump is committed to changing the way the department does business and looking at avenues to resource and to expand the Choice Program.” Once in office, Trump did just that.

On June 6, 2018, Trump signed the VA Mission Act, which made permanent the privatizing principles set forth in the VA Choice Act. The president also supported and signed the VA Accountability and Whistleblower Protection Act, which largely mirrors legislation Miller introduced in 2015. Both of these bills were sketched out in the Trump campaign’s VA white paper, which Miller wrote.

As Congress begins a new session with Miller’s old committee now in Democratic hands, some think Trump’s veterans agenda could be stalled. While both the Accountability and Mission acts passed with broad bipartisan support, some Democratic lawmakers have expressed buyer’s remorse over the laws and have pledged to limit privatization inside the agency. Still, Miller is optimistic that he can continue to work effectively.

In an October video produced by McDermott, Miller sketched out a potential lobbying path on veterans’ issues should the Democrats flip the House, as they did a few weeks later. One prescient prediction of Miller’s was that Democrats would seek to influence the rule-making around the VA Mission Act, which will dictate the standards for when veterans are offered treatment in the private sector.

Still, Miller exuded confidence and noted that he was able to pass the Choice Act under a divided Congress. “There is a lot of bipartisanship” on veterans’ issues, he explained.

“There are issues that have to be done, and regardless of who is in control, those issues will get passed,” Miller said. “It is possible to get some very big pieces of legislation done, even though there is a divided government.”

This story was edited by Aaron Glantz of Reveal and Steve Heuser and Bill Duryea of Politico and copy edited by Nikki Frick.

Jasper Craven can be reached at jclarkcraven@gmail.com. Follow him on Twitter: @Jasper_Craven.

![]()

This article was originally published in Reveal. It has been republished under the Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 license license.