The Many Ways to Gauge Results of Trump’s Deregulatory Push

Critics and boosters gravitate toward different rulemaking metrics.

When President Trump presented first-year results of his push toward deregulation, he posed at the White House in front of a towering stack of blank paper intended to dramatize the number of “burdensome” agency rules his administration has killed.

The visual was a less-than-scientific measuring stick for gauging the impact of his efforts to boost economic growth by curbing agency regulatory overreach. But finding a scientific measurement has proven difficult.

A sampling by Government Executive suggests that the methods for assessing progress in deregulation vary by philosophical and ideological leanings. And since Democrats in January took control of the House and gained oversight powers, the absence of a consensus measure is likely to emerge front and center.

In early February, the liberal-leaning Coalition for Sensible Safeguards wrote to the House Judiciary and Oversight and Reform panels seeking “robust oversight of the Trump administration’s anti-safeguard activities.” Besides bemoaning “corporate” influence and self-dealing by Trump allies, the group cited a drop-off in enforcement actions, “manipulation of cost-benefit analysis to align with Trump political goals,” attacks on science and evidence-based decision making, and “courts overturning an astonishing 90 percent” of recent deregulatory actions.

That view was a polar opposite from the presentation last October from the White House Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs, which touted its “acceleration” of Trump’s deregulatory push launched with his January 2017 Executive Order 13771. Agencies, OIRA Administrator Neomi Rao said, had eliminated $23 billion in overall regulatory costs across the government, with 176 deregulatory actions and 14 significant actions. The ratio of repeals to new rules issued was 12-1, OIRA reported, with only 14 new major rules promulgated.

Agencies withdrew or delayed 648 rules in fiscal 2018, or 2,253 since Trump’s inauguration. “In fiscal year 2019, agencies anticipate saving a total of $18 billion in regulatory costs from final rulemakings,” OIRA announced, citing an internal memo on methodology it used for calculating the savings.

Other backers of deregulation have counted the number of pages in the Federal Register. A chart compiled annually by that publication’s staff—going back to 1936—does show a dramatic drop-off in Trump’s first year. Though the Obama administration’s page counts, like those of George W. Bush, fluctuated around 70,000 or 80,000 pages, in the final year of Obama, the number shot up to 97,110 (many presidencies rush extra rules out in their final year). But in the first year of Trump, the number sunk to 61,949, the lowest since 1990. Federal Register staff told Government Executive the page count for fiscal 2018 is due at the end of March.

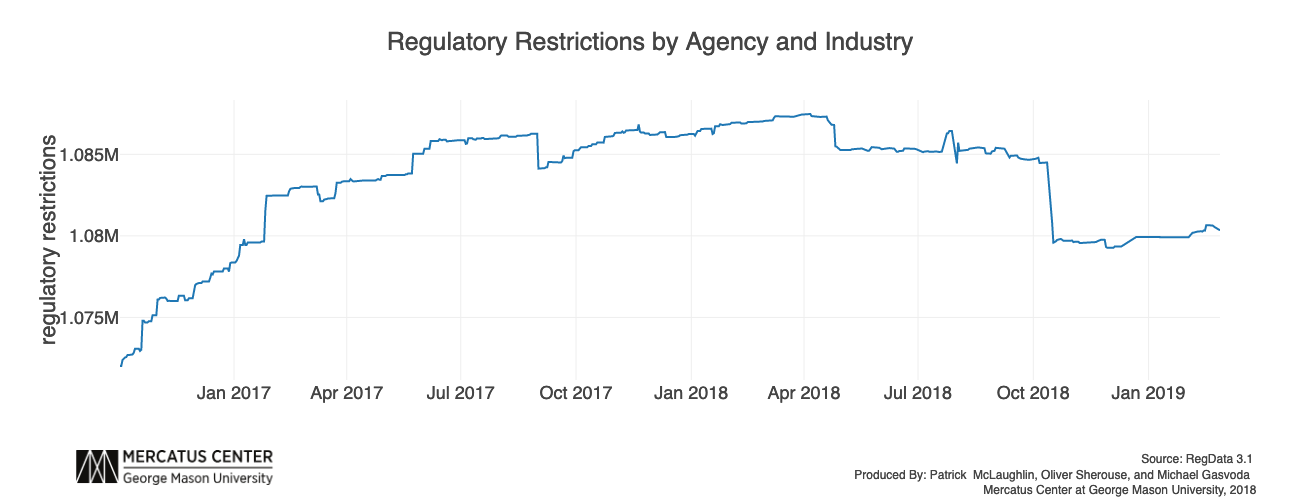

A more complex counting method is being deployed by Patrick McClaughlin, director of policy analytics at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University. His RegData Live Tracker records daily changes in the Code of Federal Regulations and counts changes in wording such as “shall, must, may not, prohibited and required.” The tracker also can quantify “the levels of regulation targeting specific industries or the quantities produced by regulatory agencies at different points in time,” the center said. “The tracker can display multiple industry or agency regulatory restriction counts at the same time.”

In his January analysis, McClaughlin noted that “something ‘big’ happened in October of 2018. That dip represents the largest discrete drop in the regulatory restrictions data for the Trump administration so far. The October drop-off entailed the removal of approximately 4,900 regulatory restrictions, most of which stem from the removal of regulations related to the now-defunct Office of Thrift Supervision and outdated regulations related to a teacher grant program that is no longer in operation,” he wrote.

“The biggest impact you see is not actually in deregulation, but in a slow-down in the making of new rules,” McClaughlin told Government Executive. “To look back in a new administration and see no growth in new federal regulations—some rules eliminated, some created, a net effect of about zero—that’s quite extraordinary,” he said. McClaughlin acknowledged that “some rules have more impact than others,” but he took no stance on the effects in specific areas.

One group that does track which rules have a greater impact is The George Washington University Regulatory Studies Center. Its graph updated in January tracking “economically significant” rules issued under recent administrations found a huge drop-off since Trump announced his deregulatory push. Under the Obama and George W. Bush administrations, the number of major rules averaged 50 or 60 annually. But in Trump’s first year, the number fell to under 20, the fewest since 1984.

“I think the administration has succeeded in slowing the pace of new regulations, and they have removed many regulations that weren’t classified as significant,” said the GW center’s director, Susan Dudley, who ran OIRA under George W. Bush.

Some of those new rules “reduce reporting burdens without affecting outcomes, which is valuable,” she said. “The president also signed a record number of congressional resolutions disapproving regulations issued late in the Obama administration. In a way, those actions were low-hanging fruit. Removing regulations takes time, and agencies have to conduct benefit-cost analysis and respond to public comment, which can take several years,” she added, citing Trump agency proposals for major changes in areas such as the Transportation Department’s required vehicle fuel efficiency standards and the Environmental Protection Agency’s rollbacks of Obama’s Clean Power plan and its Waters of the United States wetland protections.

Some of them will be challenged in court, Dudley noted.

The number that have already been challenged is being tracked by New York University’s Institute for Public Integrity. Its ongoing feature “RoundUp: Trump-Era Deregulation in the Courts” summarizes results of “litigation over federal agency rule suspensions; repeals; rescissions; efforts to weaken regulations through guidance, memoranda, amendments, or replacements; and other agency actions.”

As of late January, it showed that Trump policies have been blocked in 32 of 34 cases brought by interest groups against such agencies as the Labor, Energy, Interior and Homeland Security departments, along with EPA and Transportation.

“There’s not a lot [Trump] can show about plans to repeal rules, so far, and not a lot of rules have been ended,” said Bethany Davis Noll, the institute’s litigation director. The rules requiring a “suspension are not really the main game, and the repeal phase will involve a ton of bad case law, which is not too great for them,” she said.

The rule suspensions “teach us that there are a lot of hurdles agencies face in rolling rules back. And it’s an even bigger deal for agencies trying to repeal,” she said.

That’s because if an agency is seeking to roll back a rule that it once calculated as providing strong benefits, Noll said, “then what you’re doing is causing harm. And agencies have to justify that under several different buckets,” she added. They must prove they have the statutory authority. And, if, say, in repealing the auto emissions rule, it turns out that emissions actually go up while the statute says the agency has to conserve energy or cut emissions, “they have a big task to explain why this satisfies the statute,” she said.

On top of that, there are public comments to factor in, and some statutes that contradict each other. They “have to draft some kind of justification—so the agencies are kind of stuck,” Noll said. “If the economic principle is just not there, they could be a laughingstock.”

In courts, the agencies “don’t get a lot of deference when the judge says they have to comply” with procedural rules for notice and comment, Noll said. “They are a big hurdle to jump through for repeals” of major rules. So far, the Trump people “haven’t shown they can jump them.”