The Federal Emergency Management Agency doesn’t have a lot of fans.

By the time anyone comes in contact with FEMA, they’ve already been through a disaster. If FEMA’s work goes well, the agency tends to stay out of the spotlight. It’s only when things go wrong that FEMA’s name comes up, and then the agency tends to receive the blame.

Often FEMA’s work often leaves room for criticism, but the agency’s public-relations problems are often really the product of failures by other parts of government—at the state, local, and federal level—that are then left to be cleaned up by FEMA, Administrator Brock Long argued Monday at the Aspen Ideas Festival, hosted by the Aspen Institute and The Atlantic.

Much of what happens in a disaster is predetermined by years of decisions that preceded the storm or earthquake: decisions about what to build, where to build it, and how to maintain it. Mitigation has to be done ahead of time, but it’s seldom a priority for local residents or officials until disaster strikes.

“I don’t know what’s best for your community. You don’t want me doing mitigation for you,” Long said.

That isn’t to say that he doesn’t have strong ideas about the things that local communities should be thinking about when they go through mitigation work.

“Lack of building codes and land-use planning is killing this country,” Long said. “The built environment probably causes a third of the flooding we’ve seen in the last year. Because local officials never win by saying, ‘I would love to pass building codes.’”

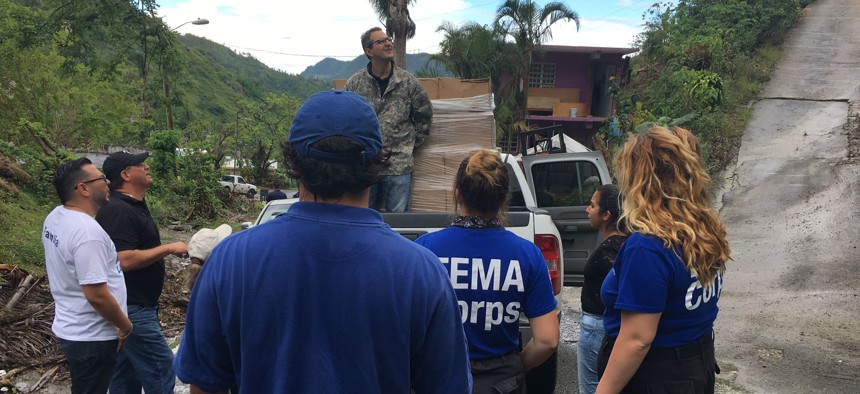

The collapse of the Puerto Rican electrical grid during Hurricane Maria was a particularly dramatic demonstration of another problem: Much of the nation’s infrastructure is crumbling and ill-maintained, from roads and bridges to dams and water systems.

“Is it FEMA’s job to make sure that infrastructure around this country is maintained? Is it?” Long said. “It’s the whole community’s response.”

What happens if state and local governments don’t do that crucial mitigation work? Then it becomes FEMA’s problem, by default though often not by any sort of rational design. Successful disaster management requires coordination and contribution from state, local, and federal government as well as the private sector. But when one or more of those actors can’t or won’t contribute—whether due to lack of resources or incompetence or disinterest—FEMA ends up holding the bag.

The question, Long said, becomes this: “What do you want me to be good at?” Puerto Rico’s economy needs rebuilding. FEMA happens to be the agency that has piles of money to spend, but it’s probably not the best situated to help. In effect, Long found himself in charge of a large portion of the island’s economy, quickly becoming the largest single employer in Puerto Rico. “Emergency managers are never taught how to generate sales tax revenue in a community that’s been devastated by storms,” he said.

The mismatch between expertise and duties also applies to the electrical system. The failure to modernize Puerto Rico’s grid before the storm is water under the bridge, or over the power lines, but now someone has to fix it. But who? And who should take charge of housing Puerto Ricans whose homes were destroyed or rendered uninhabitable?

“I’m not the Federal Electricity Management Agency,” Long said. “It’s not that the Department of Energy doesn’t want to do it. They don’t have the budget or legislative authority to do it. I’m also not a housing expert, but we’ve arranged 5 million nights in hotels.”

Arguments like this from Long might come off as self-serving justifications, given the criticism of the federal response to Maria as far too slow and far too little, given the scale of the devastation. But his perspective, from the idea of “whole-community” response to the disparate duties foisted on emergency managers, echoes that of Craig Fugate, whose stewardship of FEMA during the Obama administration won praise. When they’re forced to do so, emergency managers will try to fill gaps left by other governmental bodies. If the results aren’t great, maybe the question shouldn’t be why FEMA didn’t do the job better, but why FEMA was doing it in the first place.