How Poor Government Communication Strategy Fuels Paranoia

Responding to social media is of critical and primary importance.

By and large, Americans in 2017 have a fairly negative perception of government. And it’s far worse than it was 20 years ago. The government's failure to adapt its communication approach to reality is only making things worse.

Let's take a look at some data.

A Pew Research Center survey of 1,501 adults age 18 and older nationwide, conducted April 5-11, 2017, asked people to pick the phrase that best describes their feelings about the government: "basically content," "frustrated," or "angry." To enable a comparison of data over time, Pew has repeated this survey annually.

Since 1997, the likelihood of describing oneself as "frustrated" has remained pretty much static, at slightly more than half (55 percent now, 56 percent then). But the likelihood of calling oneself "basically content" with the government is statistically much lower, with 29 percent choosing this word in 1997 versus only 19 percent in 2017. Meanwhile, the level of anger has nearly doubled in 20 years, from 12 percent to 22 percent.

Survey respondents don't trust "the government in Washington to do what is right," and their fondness for "the swamp" is diminishing speedily. In 1997, fully 39 percent said they trusted government integrity "always/most of the time." But 20 years later, that credibility, which could be viewed as brand equity, has diminished to just 20 percent.

Mistrust of the government, of course, is part and parcel of American culture. The classic essay collection “Why People Don't Trust Government” points out three obvious reasons for the declining trust: “Age-old suspicion of authority"; the “sense that politicians have lost their dignity"; and a “deeper set of accumulated grievances with political authority, institutions and processes in general."

The book was published in 1997, before the drop in citizen trust and contentment documented by Pew's annual survey. It was around this time that social media began to take off. And there can be little doubt that this technology, by enabling citizens to engage with one another and respond to authority, has compounded the problem of mistrust in government.

It's hard to say for sure when exactly social media went mainstream. But the first bulletin board systems were online by the 1970s, and forums, newsgroups, instant messaging, and other forms of peer-to-peer communication continued to proliferate. By 1999, the Cluetrain Manifesto captured the spirit of the day:

“Whether explaining or complaining, joking or serious, the human voice is unmistakably genuine . . . Most corporations, on the other hand, only know how to talk in the soothing, humorless monotone of the mission statement, marketing brochure, and your-call-is-important-to-us busy signal. Same old tone, same old lies.”

As social media picked up steam, corporate, not-for-profit, academic and government leaders alike were confronted with a growing demand for immediate and thorough answers to their questions. As organizational consultant Gavin Rouble has pointed out, their tendency has been to do one of two ineffective things in response. One tactic is to "interpret being questioned as an attack on them," and instead of answering the question, "attacking the person who raised the question." Another is to "answer the question without actually answering."

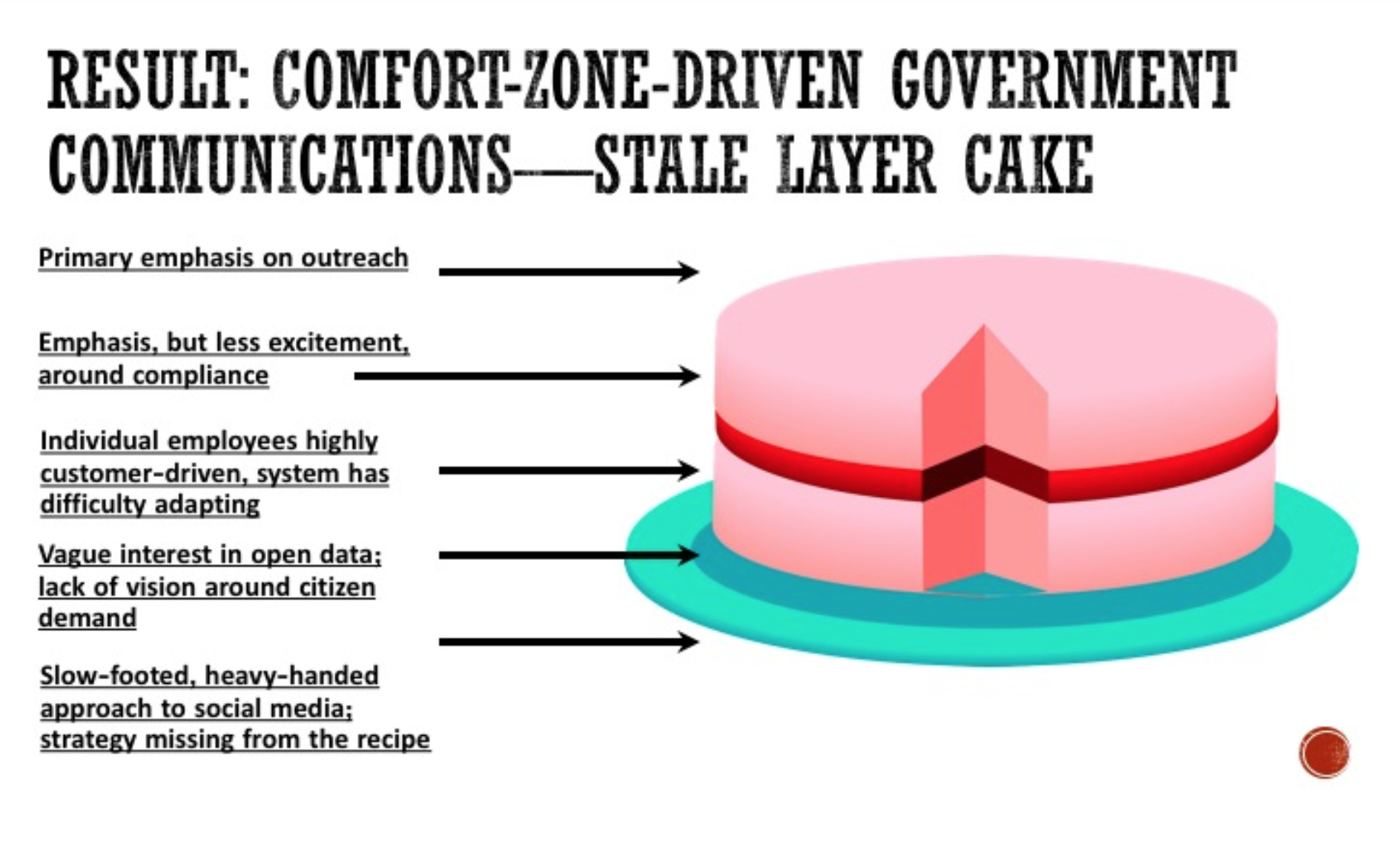

Regardless of the reason for ineffective government communications, the result is the same: a not-very-tasty (to the citizen) layer cake, where feelgood efforts are the most prominent, and the unpalatable, difficult to handle, social-media-driven conversations are not only de-prioritized, they're left out of the cake altogether.

In the middle of the cake, there is visible compliance-driven reporting, but it's hard to get people excited about complicated data that doesn't always result in a good news story.

There is also a layer dedicated to customer service: In 2011, then-President Obama issued an Executive Order mandating improvements in this area, noting that "the public deserves competent, efficient, and responsive service from the Federal Government. Executive departments and agencies must continuously evaluate their performance in meeting this standard and work to improve it."

Yet in 2017, the energy around customer service, from my experience and observation, remains at the individual level. Though there appears to be forward movement on a number of fronts (for example through the use of artificial intelligence-driven avatars), there remains a systemic problem with handling complex inquiries in multiple languages with personalized and satisfactory resolution in a timely manner—the sort of thing citizens have come to expect from successful mass retailers, such as Amazon.

Open data was the subject of another Executive Order, issued in 2013, and the Office of Management and Budget issued a Memorandum outlining the expectation that government data would be issued in open, machine-readable format. In a relatively short time (meaning the past several years) the General Services Administration's Technology Transformation Service has made a number of strides toward improving citizen’s experience with government by leveraging open data. See, for example, the work of its 18F unit with the Federal Election Commission.

However, open data is still, for the most part, not a concept that most government communication shops see as integral to their missions. The graphic below, which I produced, shows the result of ineffective government communication strategy, using the layer cake analogy.

The U.S. government should have a clear and well thought out communication strategy, based on communication standards that stand regardless of which political party is in power. (Full disclosure: I co-authored a research paper on this issue for the Federal Communicators Network, for which I volunteer.)

The strategy should be updated annually, and success should be measured according to a clear set of goals and objectives. The U.K. has done this for several years.

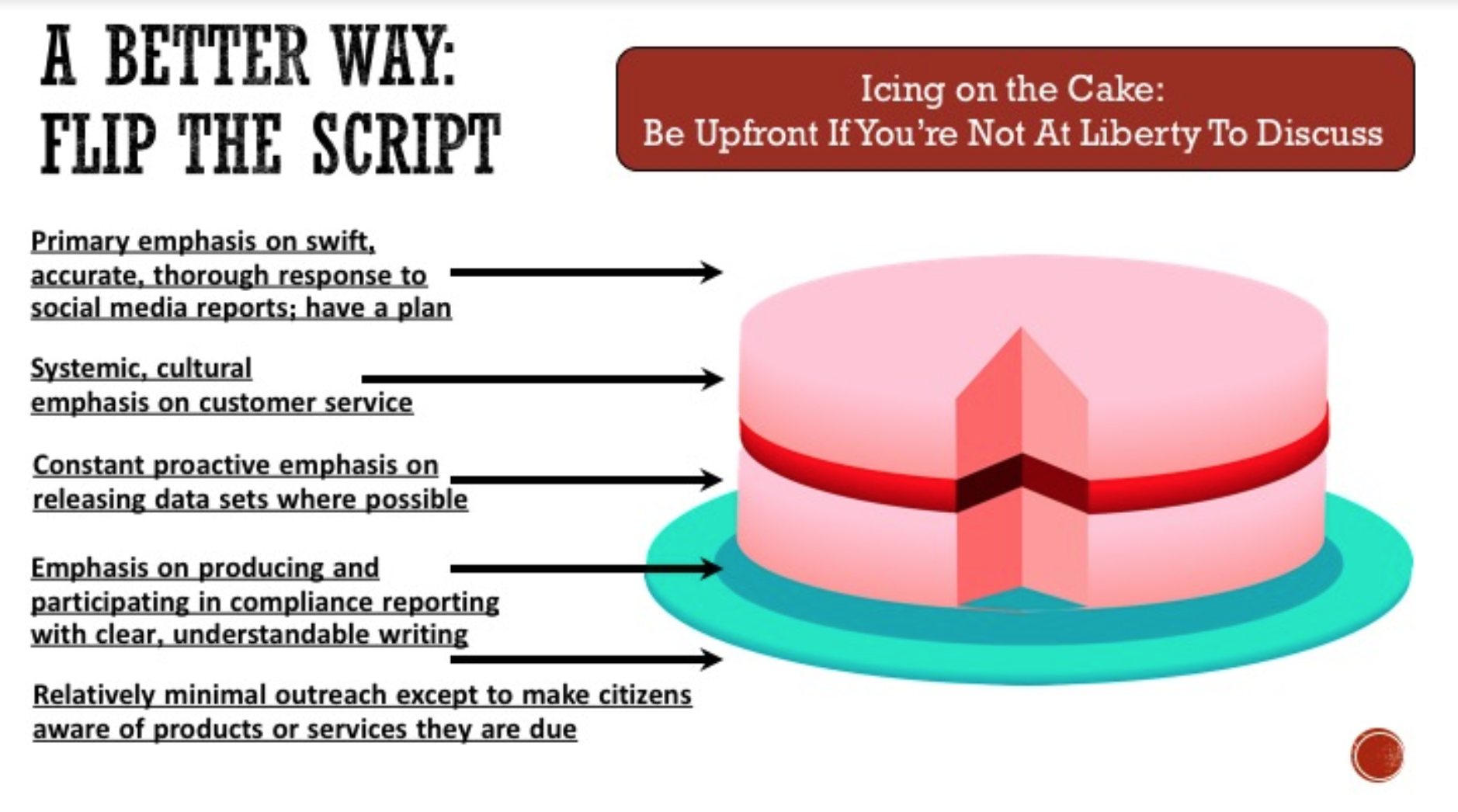

Until the U.S. formally develops a strategy, we can establish a general, citizen-centered framework that takes into account the realities of today's social attitudes toward government.

The graphic below shows what this might look like: Responses to social media grace the top of the cake, followed by customer service, then open data, then compliance reporting, and finally outreach efforts based primarily on making citizens aware of the products and services they are entitled to.

The bottom line is this: Citizens are more educated and empowered than ever.

At the same time, their perceptions of government are deeply negative, and the situation is not getting better.

As such, if the government does not adapt effectively, citizen-to-citizen communication will ultimately eclipse what federal officials have to say.

Moreover, mistrustful, angry and frustrated citizens are likely to misinterpret legitimate government communications as nefarious. The consequences of this misinterpretation include compounded hostility toward government, with myriad potential negative consequences. One of the most prominent among these is the tendency to favor unsourced “fake news” over accurate data.

The government can respond effectively to this situation by reversing its traditional approach to communication. In this framework, responding to social media is of critical and primary importance.

To make this shift effectively, the default attitude must be to communicate, even if it’s to say that “we’re not at liberty to say.”

It goes without saying that corruption must be rooted out and eliminated regularly in order for any communication strategy to work.

Copyright 2017 by Dannielle Blumenthal. All opinions are the author's own and do not necessarily represent the views of her employer or any other organization or entity.