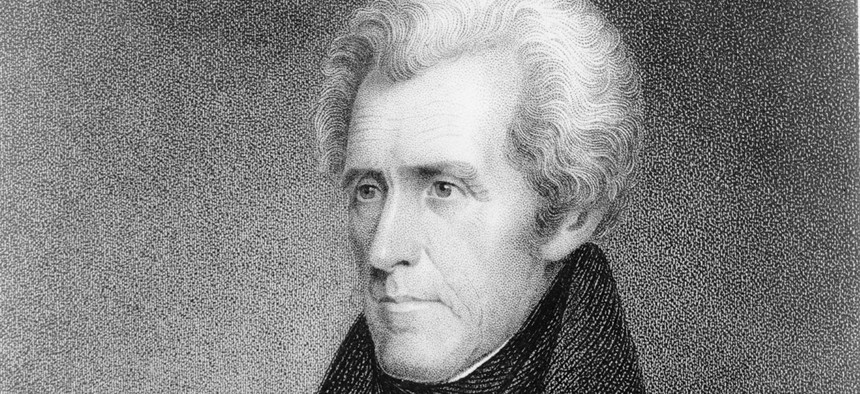

J.B. Longacre's portrait of Andrew Jackson was engraved sometime between 1815 and 1845. Library of Congress

Donald Trump and the Legacy of Andrew Jackson

There’s no shortage of parallels between the two populists—but there’s at least one crucial difference.

Steve Bannon, the media executive and soon-to-be White House strategist, has been describing Donald Trump’s victory as just the beginning. “Like [Andrew] Jackson’s populism,” he told the Hollywood Reporter, “we’re going to build an entirely new political movement.”

Newt Gingrich has compared Trump to Jackson for some time. Rudolph Giuliani declared on election night that it was “like Andrew Jackson’s victory. This is the people beating the establishment.” That may seem a comforting comparison, since it locates Donald Trump in the American experience and makes his election seem less of a departure.

Is Trump’s victory really like Jackson’s? On the surface, yes: In 1828, an “outsider” candidate appealed directly to the people against elites he called corrupt. A deeper look at Jackson’s victory complicates the comparison, but still says much about America then and now.

Jackson’s road to victory began with a defeat. He was a Tennessee politician and plantation owner turned soldier, a man who, unlike Trump, had deep experience in government. As a general, he became the greatest hero of the War of 1812, and capitalized on his fame by running for president in 1824. But the electoral votes were split between four candidates. The presidency was decided by the House of Representatives, which chose John Quincy Adams, the highly qualified secretary of state.

Jackson politely congratulated the winner, but was seething. He soon declared the system was rigged. The Jacksonians’ phrase was “bargain and corruption”—they said the House speaker, Henry Clay, had thrown the vote in exchange for being named secretary of state. This conspiracy theory added an element of rage to Jackson’s basic argument that he was simply owed the presidency. Although the House had voted in accordance with the Constitution, Jackson insisted that he should have automatically won because “the majority” of the people supported him. (He’d actually won a plurality of the popular vote, 40 percent, which was politically significant but had no legal bearing.)

With an eye to the next election, he set out to upend the political system, which had been running predictably for a generation. A party founded by Thomas Jefferson had installed four consecutive presidents. Most elections were not even close. Relatively few people voted, and many lacked voting rights. But the franchise was expanding to include all white men, and boisterous new political forces were sweeping the growing nation.

Jackson and his allies spent four years building a popular movement in favor of majority rule. They worked to delegitimize President Adams, promoting the “corrupt bargain” conspiracy theory and blocking his programs in Congress. In their 1828 rematch, Jackson defeated Adams in a landslide. His 1829 inauguration was recorded as a triumph of the people, who mobbed the White House in such numbers that they trashed it. It’s this moment to which Giuliani referred on election night 2016.

When Bannon spoke of founding a “new political movement,” though, he was referring to the period immediately afterward. Jackson and his allies created a new organization, the Democratic Party. His opponents were forced to up their own political game by founding a new opposition party, and American politics began growing into the two-party rivalry that we know today. The old, staid political order cracked up.

It’s too early to predict if 2016 will turn out to be another long-term inflection point. (Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, and Barack Obama also seemed to have changed the game when they took power.) But there are resonances between Jackson and Trump.

Jackson, like Trump, made innovative use of the media. He offered nothing like Trump’s running commentary on Twitter, nor did he even make formal campaign speeches, which were considered undignified for presidential candidates. But he did use newspapers, which were growing in number and importance. A subscriber to as many as 17 papers, he understood the changing media landscape better than his critics did. He personally involved himself in news coverage, once writing a letter urging that a friendly, but alcoholic, newspaperman must be kept sober long enough to “scorch” one of Jackson’s rivals. He counted newspaper editors among his close advisers, and made sure they established a pro-Jackson newspaper in Washington when he took office. (His famous “kitchen cabinet” included these newsmen.) Trump, of course, has made analogous moves by managing his own media relations, asking Sean Hannity for advice and inviting Bannon to serve as his strategist.

Jackson, like Trump, won over many white working-class voters, who brushed aside critics who warned that he was unstable and a would-be dictator. He maintained their loyalty even though, like Trump, he was of the elite. Though not born to wealth as Trump was, Jackson made his fortune on the early American frontier. He did not clear out Washington elites so much as bring a new coalition of elites to power: New York politicians and Pennsylvania businessmen allied with Southern slaveholders. Jackson tended to their special interests. He also used political patronage to stuff the government with Jackson loyalists. There is something Jacksonian both in Trump’s promise to “drain the swamp” of Washington and his early moves to refill the swamp with wealthy friends, loyal supporters, and family members.

Jackson mixed his public duties and his business. As an Army general he took land from Indians, which he and his friends then purchased to build lucrative cotton plantations. Trump promoted his real-estate investments while campaigning for president, and acknowledges that he “might have” discussed his global business interests in his talks with overseas leaders since the election. But as president-elect, Jackson asked a friend to help settle his business affairs so he could focus on becoming president. President-elect Trump has yet to separate himself from his business.

Trump’s Jackson-style appointment of Bannon points to a particularly strange resonance. Bannon described his website as “the platform for the alt-right,” a tag for small groups of people who have promoted ideas such as a white ethnic state. Although Trump disavowed them, they remain among Trump’s vocal supporters. What they aspire to is a nation like the one Andrew Jackson knew. He lived in a time of exclusively white rule—government “on the white basis,” as Jackson’s political successor Stephen A. Douglas later put it. The Civil War and the civil-rights movement discredited that notion, but it’s apparently still attractive to a few.

For all the similarities, there’s a big difference between Jackson’s victory and Trump’s: Jackson’s greatest political achievement was the widening of democratic space. He brought new groups of voters into the political system. Expanding voting rights and a growing media perfectly coincided with his attention-grabbing campaigns, and the popular vote total tripled—tripled—between Jackson’s loss in 1824 and his victory in 1828.

Trump, too, aspired to widen the electorate, but with less success. It’s true that he attracted some former Democrats, and received more votes than any Republican candidate in history, slightly more than George W. Bush in 2004. But in key states his party made it harder to vote. Among those who did participate, as of this writing, Trump lost the popular vote to Hillary Clinton by more than 2.3 million. While the national popular vote has no legal significance, it matters politically, as Jackson grasped in the 1820’s. It matters enough to Trump that he volunteered a conspiracy theory to explain his failure to win it.

Trump’s victory in the Electoral College was not a repeat of Jackson’s 1828 popular landslide. It was a repeat of 1824, a transitional year when the president was determined by the mechanics of the Constitution. In this replay of the drama, the role of Andrew Jackson does not fit Donald Trump. Rather he plays the part of John Quincy Adams, the man who benefits from the elaborate American systems designed to filter the will of the people. If Trump intends to become a Jacksonian man of the people, he will have to do something to attract the majority who voted for candidates other than him.

(Image via Flickr user Joe Campbell)