Ben Milakofsky/Interior Department

Yosemite, Through John Muir's Words

Reflecting on the naturalist’s observations, as President Obama celebrates 100 years of the National Park Service.

President Obama and the First Family will arrive in Yosemite on Friday, and spend the weekend celebrating the National Park Service’s 100th anniversary. The park actually antedates the agency that now cares for it; the naturalist John Muir helped create it in 1890.

Muir, a Scottish-American who retained his iconic long beard and boyish energy even in old age, was the fiercest proponent of the Sierra Nevada, exploring every inch of Yosemite—its plants and animals, its sounds and smells. He even took Theodore Roosevelt on a visit there in 1903.

He wrote extensively about the area for The Atlantic during the late 1800s and early 1900s. In our August 1899 issue, he gave a passionate account of the new national park, writing:

Of all the mountain ranges I have climbed, I like the Sierra Nevada the best. Though extremely rugged, with its main features on the grandest scale in height and depth, it is nevertheless easy of access and hospitable; and its marvelous beauty, displayed in striking and alluring forms, wooes the admiring wanderer on and on, higher and higher, charmed and enchanted. Benevolent, solemn, fateful, pervaded with divine light, every landscape glows like a countenance hallowed in eternal repose; and every one of its living creatures, clad in flesh and leaves, and every crystal of its rocks, whether on the surface shining in the sun or buries miles deep in what we call darkness, is throbbing and pulsing with the heartbeats of God. All the world lies warm in one heart, yet the Sierra seems to get more light than other mountains. The weather is mostly sunshine embellished with magnificent storms, and nearly everything shines from base to summit,—the rocks, streams, lakes, glaciers, irised falls, and the forests of silver fir and silver pine. And how bright is the shining after summer showers and dewy nights, and after frosty nights in spring and autumn, when the morning sunbeams are pouring through the crystals on the bushes and grass, and in winter through the snow-laden trees!...

Of this glorious range the Yosemite National Park is a central section, thirty-six miles in length and forty-eight miles in breadth. The famous Yosemite Valley lies in the heart of it, and it includes the head waters of the Tuolumne and Merced rivers, two of the most songful streams in the world; innumerable lakes and waterfalls and smooth silky lawns; the noblest forests, the loftiest granite domes, the deepest ice-sculptured canons, the brightest crystalline pavements, and snowy mountains soaring into the sky twelve and thirteen thousand feet, arrayed in open ranks and spiry pinnacled groups partially separated by tremendous cañons and amphitheatres; gardens on their sunny brows avalanches thundering down their long white slopes, cataracts roaring gray and foaming in the crooked rugged gorges. and glaciers in their shadowy recesses working in silence, slowly completing their sculpture; new-born lakes at their feet, blue and green, free or encumbered with drifting icebergs like miniature Arctic Oceans, shining, sparkling, calm as stars.

Nowhere will you see the majestic operations of nature more clearly revealed beside the frailest, most gentle and peaceful things. Nearly all the park is a profound solitude. Yet it is full of charming company, full of God’s thoughts, a place of peace and safety amid the most exalted grandeur and eager enthusiastic action, a new song, a place of beginnings abounding in first lessons on life, mountain-building, eternal, invincible, unbreakable order; with sermons in stones, storms, trees, flowers, and animals brimful of humanity. During the last glacial period, just past, the former features of the range were rubbed off as a chalk sketch from a blackboard, and a new beginning was made. Hence the wonderful clearness and freshness of the rocky pages.

Muir knew that the natural wonders of the country could easily be taken away. At the time of his writing, he saw the coastal redwoods of California and the spruce of Oregon and Washington succumb to the commercial demand for lumber. To Muir, this made the creation of national parks an urgent project.

He so loved trees that he once climbed a pine during a particularly bad storm just to see what it was like to be a tree in heavy winds. In the April 1900 issue, hedescribed Yosemite’s trees in exhaustive detail, including its sugar pines:

No traveler, whether a tree lover or not, will ever forget his first walk in a sugar-pine forest. The majestic crowns approaching one another make a glorious canopy, through the feathery arches of which the sunbeams pour, silvering the needles and gilding the stately columns and the ground into a scene of enchantment.

It was in that essay that Muir described meeting Ralph Waldo Emerson, a leader of the Transcendentalist movement and prominent writer for The Atlantic, in Yosemite in 1871. After many failed attempts to get Emerson to go “rough camping” with him, Muir said to Emerson, sitting in Mariposa Grove, “You are yourself a sequoia. Stop and get acquainted with your big brethren.” Emerson, however, was “past his prime” and would not join him.

Muir devoted the same loving attention to the flowers of Yosemite as he had lavished on its trees. As he wrote in the August 1900 issue:

In general views of the Park scare a hint is given of its floral wealth. Only by patiently, lovingly sauntering about in it will you discover that it is all more or less flowery, the forests as well as the open spaces, and the mountain tops and rugged slopes around the glaciers as well as the sunny meadows.

Even the majestic cañon cliffs, seemingly absolutely flawless for thousands of feet and necessarily doomed to eternal sterility, are cheered with happy flowers on invisible niches and ledges wherever the slightest grip for a root can be found; as if Nature, like an enthusiastic gardener, could not resist the temptation to plant flowers everywhere.

One of his final observations of the national park for The Atlantic came during the April 1901 issue, when he excitedly described Yosemite’s waterways. He recounted one specific location in the park of which he was particularly fond—the north fork of Owens River—which he says had “wonderful champagne water” that was best imbibed by leaning down and drinking directly from its source, “lest the touch of a cup might disturb its celestial flavor.”

A story from that essay captures the joy Muir found there:

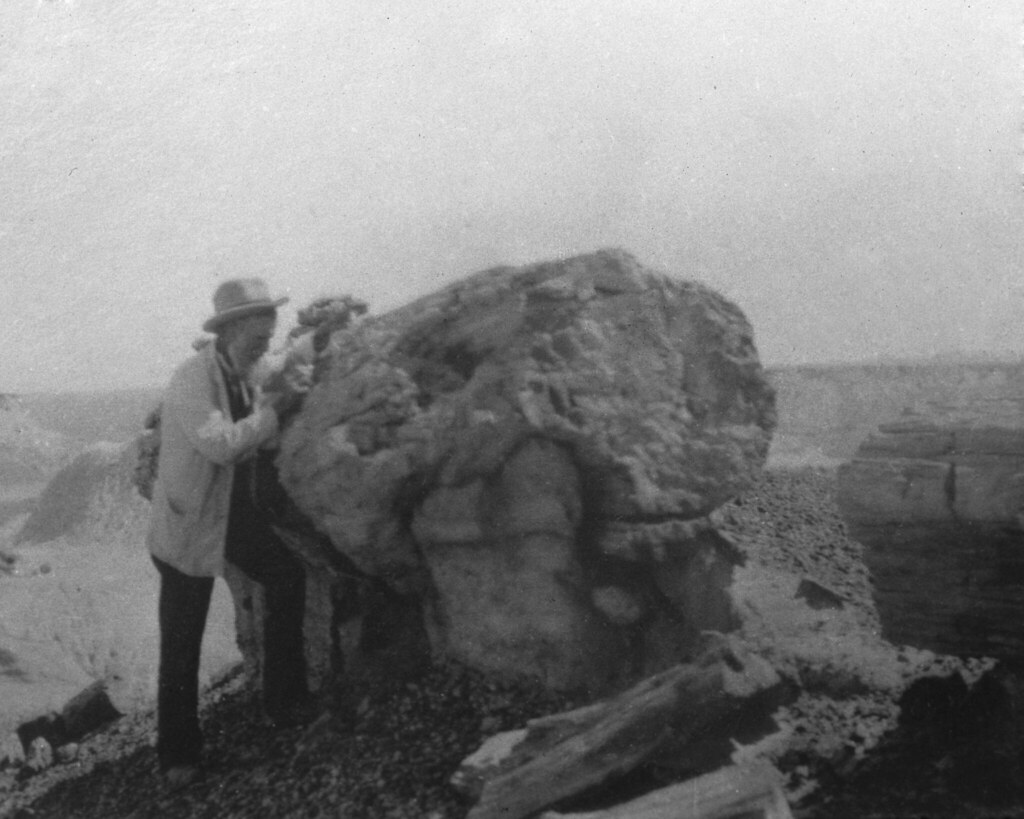

In Yosemite Valley, one morning about two o'clock, I was aroused by an earthquake; and though I had never before enjoyed a storm of this sort, the strange, wild thrilling motion and rumbling could not be mistaken, and I ran out of my cabin, near the Sentinel Rock, both glad and frightened, shouting, "A noble earthquake!" feeling sure I was going to learn something.

A boulder soon gave way up the valley, tumbling down, leveling trees, and breaking into piece. After the dust settled and the chaos calmed, he observed:

Nature, usually so deliberate in her operations, then created, as we have seen, a new of features, simply by giving the mountains a shake,—changing not only the high peaks and cliffs, but the streams. As soon as these rock avalanches fell every stream began to sing new songs; for in many places thousands of boulders were hurled into their channels, roughening and half damming them, compelling the waters to surge and roar in rapids where before they were gliding smoothly. Some of the streams were completely dammed, driftwood, leaves, etc., filling the interstices between the boulders, thus giving rise to lakes and level reaches; and these, again, after being gradually filled in, to smooth meadows, through which the streams now silently meander; while at the same time some of the taluses took the places of old meadows and groves. Thus rough places were made smooth, and smooth places rough. But on the whole, by what at first sight seemed pure confusion and ruin, the landscapes were enriched; for gradually every talus, however big the boulders composing it, was covered with groves and gardens, and made a finely proportioned and ornamental base for the sheer cliffs. In this beauty work, every boulder is prepared and measured and put in its place more thoughtfully than are the stones of temples.

In his writings, he explored nature with such reverence that the trees, insects, and animals became characters. He wanted visitors of Yosemite to appreciate their surroundings as much as he did. That became clear in the November 1898 issue, when he wrote:

Travelers in the Sierra forests usually complain of the want of life. “The trees,” they say, “are fine, but the empty stillness is deadly; there are no animals to be seen, no birds. We have not heard a song in all the woods.” And no wonder! They go in large parties with mules and horses; they make a great noise; they are dressed in outlandish unnatural colors; every animal shuns them. Even the frightened pines would run away if they could. But Nature-lovers, devout, silent, open-eyed, looking and listening with love, find no lack of inhabitants in these mountain mansions, and they come to them gladly. Not to mention the large animals or the small insect people, every waterfall has its ouzel and every tree its squirrel or tamias or bird: tiny nuthatch threading the furrows of the bark, sheerily whispering to itself as it deftly pries off loose scales and examines the curled edges of lichens; or Clarke crow or jay examining the cones; or some singer-oriole, tanager, warbler-resting, feeding, attending to domestic affairs. Hawks and eagles sail overhead, grouse walk in happy flocks below, and song sparrows sing in every bed of chaparral. There is no crowding, to be sure. Unlike the low Eastern trees, those of the Sierra in the main forest belt average nearly two hundred feet in height, and of course many birds are required to make much show in them, and many voices to fill them. Nevertheless, the whole range, from foothills to snowy summits, is shaken into song every summer; and though low and thin in winter, the music never ceases.

Muir’s way of looking at America’s national parks may strike the contemporary reader as alien. The president’s visit comes as the National Park Service is beset by internal controversies, and there seem to be weekly incidents of visitors failing to respect what conservationists for over a century have tried to protect. But overall, visits to National Parks have steadily increased, topping 300 million for the first time in 2015. More and more Americans, it seems, may feel as Muir did in 1873: “The mountains are calling and I must go.”