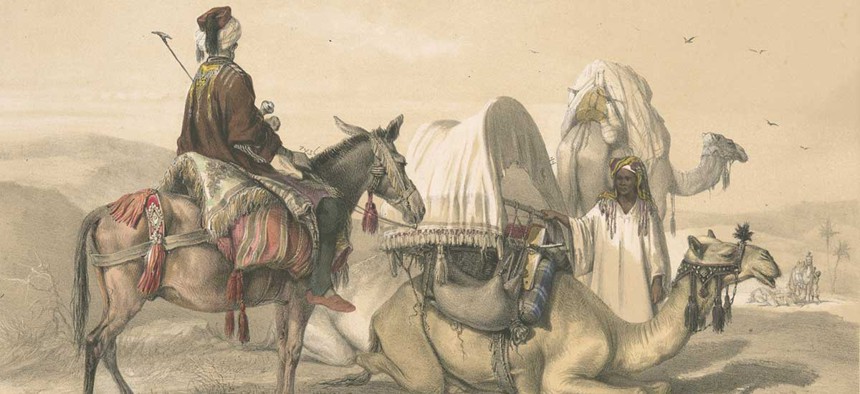

Kâfileh with camel bearing the Hodejh by Prisse d'Avennes. New York Public Library

Obama Has Signed a Bill Erasing the Words 'Oriental' and 'Negro' From Federal Legislation

The bill affects two late-1970s laws.

Starting May 20, “Oriental” will no longer be used as shorthand for Asian Americans in US federal law. The word “Negroes,” too, is out.

President Barack Obama signed the bill during Asian Pacific American Heritage Month and ahead of a trip to Vietnam and Japan. “At long last this insulting and outdated term will be gone for good,” said Congresswoman Grace Meng, who sponsored the bill, in a press release.

The bill affects two late-1970s laws, which had originally defined “minority” as “a Negro, Puerto Rican, American Indian, Eskimo, Oriental, or Aleut or is a Spanish speaking individual of Spanish descent.” The new definition of an ethnic minority will read: “Asian American, Native Hawaiian, a Pacific Islander, African American, Hispanic, Puerto Rican, Native American, or an Alaska Native.”

The word “Oriental” has become an anathema for many Asian Americans, even though it was a ubiquitous term for anyone from, well, basically, not Europe or the Americas, until the mid-20th century. In 2016 “Oriental” sounds like the kind of thing only white people’s relatives say.

A quick refresher: The word “Oriental” to describe a person or place comes from the Latin “oriens,” meaning “eastern,” or “rising” (as in the sun). Things that were “Oriental” gained great popularity in 19th-century Europe through the French Orientalisme movement, an era of art and literature that conflated foreignness with the exotic. People and motifs from the nebulous “East”—which ranged anywhere from Japan to the Ottoman Empire—became a form of decoration and entertainment: Japanese prints inspired French ornamentation, while harems were imagined by European painters who had probably never seen one.

In the US, distaste for the word can be traced to critic Edward Said’s 1978 book, Orientalism. In it, he argues that the “Orient” was a creation of the British and French to refer to “a place of romance, exotic beings, haunting memories and landscapes, remarkable experiences.” The more scholars and writers referred to this Orient, the more they defined the non-American, non-European world as something “other” than normal. According to Said, this proliferated a system of cultural and political domination over these “Orientals.”

Today, references to Oriental people conjure the same kind of outdated distance between “us” and “them,” and lump humans from a broad range of cultures, histories, and nations into one entity.

Slowly but surely, the word is being teased out of American-English usage. In 2002, Washington state legislature made it illegal to use “Oriental” in reference to people on state documents, and in 2009 then New York governor David A. Paterson signed a similar bill.

In 1989 the University of Missouri School of Journalism issued a“Dictionary of Cautionary Words and Phrases” to let young reporters know that “Asian American” was preferable to Oriental. Twenty years later, the AP style guide made the same recommendation to forego the term and refer instead to Asian people’s specific nationalities. The guide does note, however, that “Oriental rug is standard.”