NOAA Offers a Space-Based View of 2015's 'Hyperactive' Hurricane Season

The last time three eastern-Pacific hurricanes developed this early was 1956.

Misdirected flocks of little, red crabs in California aren’t the only sign of a strengthening El Niño. There was also the bippety-bam-boom emergence of three eastern-Pacific hurricanes since May, something that hasn’t happened since 1956.

The folks at Climate.gov have posted an illuminating guide to what they call a “hyperactive” Pacific hurricane season . The long and short of it is that El Niño is driving up the ocean’s temperature and reducing wind shear, creating the perfect environment for frequent and powerful cyclones. (Though Carlos was weak, both Andres and Blanca reached Category 4 wind speeds of 140 to 150 mph.) Here’s part of that discussion:

On May 27, NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center issued its annual hurricane outlooks for the eastern Pacific hurricane season, the central Pacific hurricane season, and the Atlantic hurricane season . The outlooks for both the eastern and central Pacific hurricane regions called for a 70% chance of an above-normal season. For the eastern Pacific, the predicted ranges of activity (with a 70% likelihood for each range) included 15-22 named storms, with 7-12 becoming hurricanes, of which 5-8 could be major hurricanes. These ranges are centered well above the season averages of 15-16 named storms, 8 hurricanes, and 4 major hurricanes. If the predicted upper bound of eight major hurricanes occurs, it would tie for the most recorded in the 1971-2014 observational record.

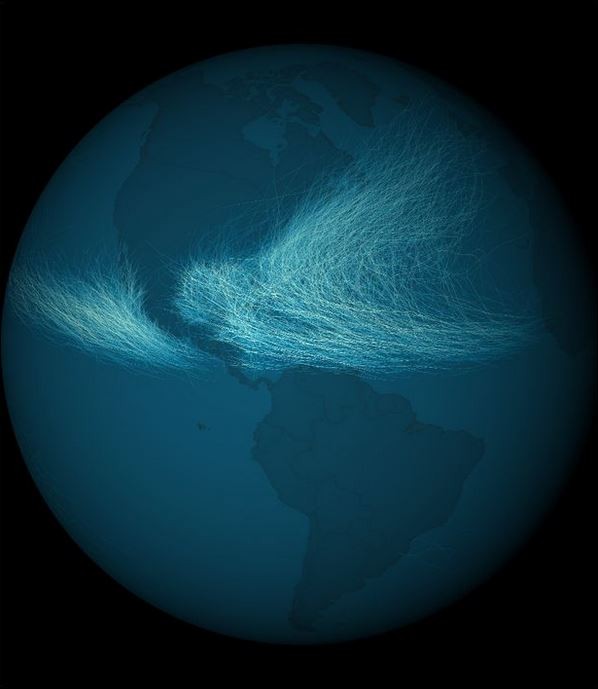

With a strong El Niño predicted for this year, they add, we can likely “expect many more tropical storms, hurricanes, and major hurricanes over the eastern Pacific before the season ends” on November 30. That’s not great news for those living in western Mexico. But it’s not such a huge deal for the U.S., as winds tend to steer hurricanes away from the coastline, as shown in this model of storm tracks since 1842 :