Underemployment is considered a less empirical measure of the labor market than unemployment, because what it is measuring most accurately is personal disappointment . You'd think expectations rise with education attainment. But self-reported underemployment declines as you spend more years in school. Maybe that's another bit of data suggesting that, both financially and emotionally, a college degree still pays off.

kmlmtz66/Shutterstock.com

The Gender-Wage Gap Is Shrinking—or Is It?

Why Millennial women will make more than their mothers, but less than their brothers.

The wage gap between young male and female workers is historically low. The wage gap between young male and female workers is growing. Yes, both things can be true at the same time.

Intergenerational economic inequality is declining: The gap between male and female wages among Millennials is lower than it was among boomers or Gen-X. But the pernicious gender gap is reasserting itself as you look higher up in the corporate ladder. Income data shows that middle-aged women fall behind their male peers, particularly when they take time off to be moms. Men with families and children, on the other hand, earn more than their same-aged bachelor colleagues, according to Pew . So as Millennials grow up, today's entry-level inequality could still yield to middle-age inequality.

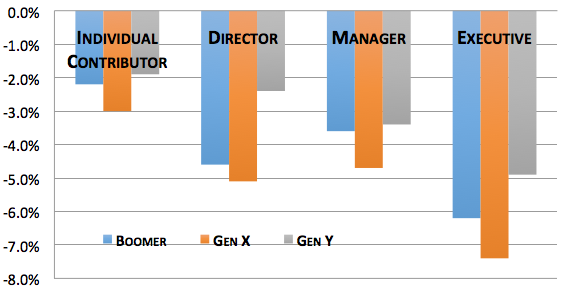

If that paragraph doesn't entirely make sense to you, this graph should make things crystal clear. It comes from data in a new PayScale and Millennial Branding study. You can see Millennials (in grey) have the smallest gender-wage gap at all levels, but the difference in pay deepens as you move up the corporate ladder.

The Gender Wage Gap: Percent Difference in Pay

This is what economists call the "sticky floor" theory of the gender wage gap. Women make very close to men coming out of college, but as men climb the corporate ladder, female salaries stick to the ground. Consider that women account for 49 percent of the bottom 99 percent of earners, but just 11 percent of the 1 percent, and just 9 percent of the top 0.1 percent of earners, according to one recent paper .

* * *

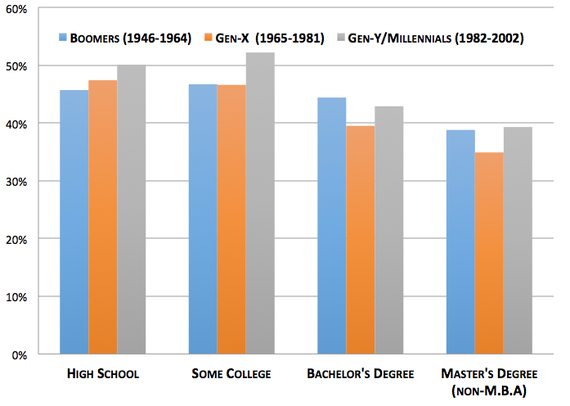

Another fascinating nugget from the PayScale report asks Americans if they consider themselves under employed. That is, do they feel underpaid or unfulfilled for their level of education?

If you feel underemployed in your current job, the good and bad news is that you're not alone. At least 20 percent of every age group, at every level of educational attainment, is disappointed by their pay or job. But underemployment declines by education level.

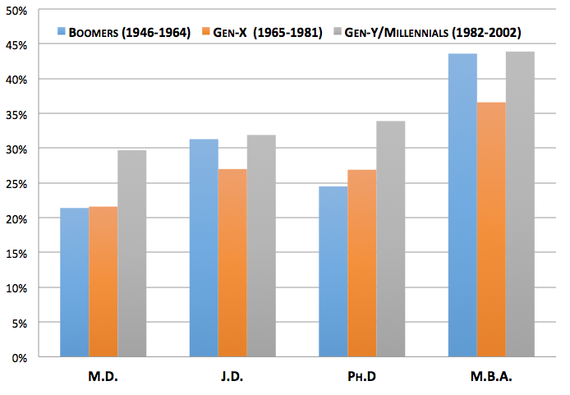

Percent of Americans Who Consider Themselves Underemployed, by Education Level

It's fairly surprising that business-school graduates are more likely to feel underemployed than a typical college graduate, even though they earn much more. Perhaps it's an acknowledgement that underemployment is not a fixed definition, but a sliding scale that moves with our expectations.

Percent of Americans Who Consider Themselves Underemployed, by Degree