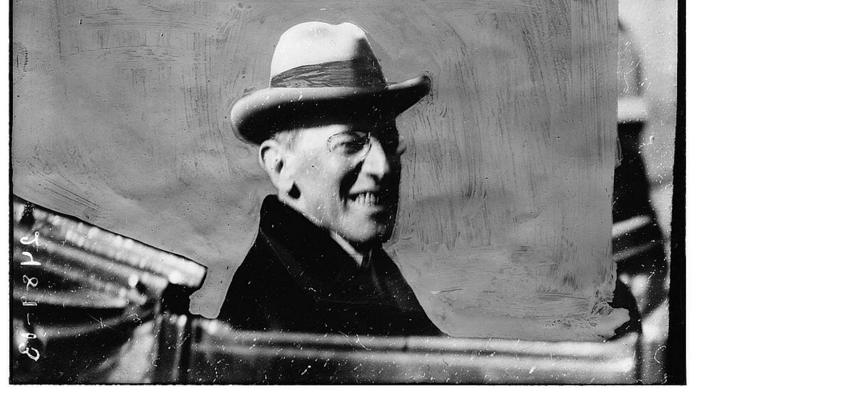

Library of Congress

When Woodrow Wilson Segregated the Federal Workforce

An inconvenient truth about a former president.

This week, Woodrow Wilson became the latest historical figure to be drawn into ongoing battles over the legacy of racism at colleges and universities. A group of Princeton students demanded that Wilson’s name be erased from campus facilities and programs--a huge undertaking, given that there’s an entire school at the university (where Wilson served as president before entering the White House) named in his honor.

While some people may seek to dismiss this crusade as an exercise in political correctness, Vox’s Dylan Matthews points out today that Wilson was an ardent segregationist, even by the standards of his time--especially when it came to managing the federal workforce.

Here’s how William Keylor, professor of history and international relations at Boston University, describes the atmosphere in government when Wilson took office in 1913:

Washington was a rigidly segregated town--except for federal government agencies. They had been integrated during the post-war Reconstruction period, enabling African Americans to obtain federal jobs and work side by side with whites in government agencies. Wilson promptly authorized members of his cabinet to reverse this long-standing policy of racial integration in the federal civil service.

At a cabinet meeting in April 1913, Matthews writes, Postmaster General Albert Burleson made the case for resegregating the Railway Mail Service. Hearing no objection from Wilson, Burleson went ahead. Soon, the discriminatory policy expanded, according to a history of African Americans’ experience at the Postal Service published by the National Postal Museum:

Segregation was quickly implemented at the Post Office Department headquarters in Washington, D.C. Many African American employees were downgraded and even fired. Employees who were downgraded were transferred to the dead letter office, where they did not interact with the public. The few African Americans who remained at the main post offices were put to work behind screens, out of customers’ sight.

Both the Post Office and the Treasury Department also created separate bathrooms and lunchrooms for African American and white employees.

Wilson’s predecessors in the post-Civil War era had appointed several African Americans to high-ranking government posts. He not only put a stop to that practice, but in 1914 instituted a policy requiring federal job seekers to attach photographs to their applications.

Despite protests from civil rights leaders during his administration, Wilson refused to budge on such measures. “I would say that I do approve of the segregation that is being attempted in several of the departments…,” he wrote at one point, declaring that it was in African Americans’ interest to be separate from their white coworkers.

That’s at best an inconvenient truth for Princeton’s Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs, which is supposed to be training students for service in federal agencies.