A polar bear walks in Alaska in 2007. Patrick Kelley/U.S. Coast Guard

The Art of Ignoring Things

The brain is better at blocking out distractions than previously thought.

Let’s begin with a little experiment: Whatever you do, as you’re reading this short article, don’t think about polar bears.

This is, you may have recognized, a classic thought exercise from the writer Fyodor Dostoyevsky. In Winter Notes on Summer Impressions, in a passage that launched a thousand psychology theses, he wrote, “Try to pose for yourself this task: not to think of a polar bear, and you will see that the cursed thing will come to mind every minute.”

In clinical terms, this phenomenon—of being told to suppress a thought, which then only makes that thought more persistent—is called Ironic Process Theory. Several studies in recent decades have confirmed Dostoyevsky’s observation: Essentially, it’s not helpful to be told what not to think about.

But new research out of Johns Hopkins finds that being told to ignore specific information can actually work, and can make people more efficient in finding the information they’re seeking.

“I’m interested in trying to make people better at finding stuff,” said Corbin Cunningham, a graduate fellow in the Department of Psychological & Brain Sciences at Hopkins, and the lead author of a study published last month in the journal Psychological Science. “Imagine you’re a professional searcher like a radiologist. The act of finding something kind of comes with two parts: It comes with knowing what you’re looking for and being able to disassociate from distracting information.”

In other words, you need to know what you’re seeking—perhaps medical imagery that indicates a disease—and you need to know what visual information can be thrown out during that search. This brings us to our next experiment, courtesy of Cunningham’s research.

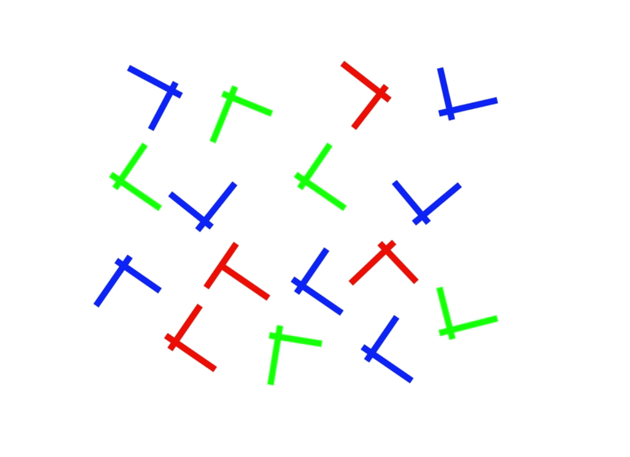

Take a look at the image below, and see if you can locate the “T.”

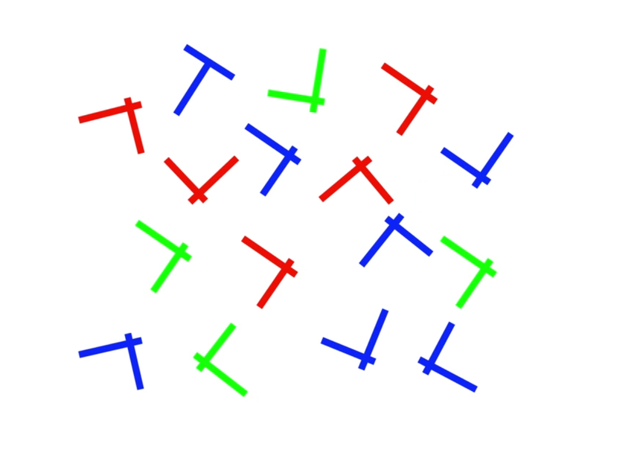

Did you find it? Okay, now, for the next image, I want you to do the same thing but I’ll give you a hint: The “T” is not going going to be the color red.

How’d it go?

In Cunningham’s research study participants were asked to carry out a similar task. Cunningham and his fellow researcher, Howard Egeth, wanted to figure out whether learning to ignore a designated color would, over time, make a difference in how quickly someone could find a target. What they discovered: Being told what to ignore hindered people at first, but over time it made them identify their target a lot faster. Their finding challenges the conventional wisdom that being told to ignore something is just plain distracting. “The idea that it’s always stuck in your mind, kind of permeating all of your thoughts,” Cunningham told me. “Even when you’re trying to ignore something, you’re actively suppressing it.”

This latest research suggests that even when the brain is actively suppressing something, it becomes more efficient in doing so over time. “We find that people can do this dual process where they get really, really good at ignoring the information,” Cunningham said, “So it actually can work to your benefit.”

The neurological mechanism that’s behind all this isn’t yet clear, and is something that Cunningham wants to map. But there are still potential real-world applications for a finding of this nature. There’s Cunningham’s example of radiologists, for instance, who might benefit from training that includes an emphasis on what kind of imaging can always be ignored. He also gives the example of baggage screeners, who could become more efficient in finding dangerous items by knowing definitively what kind of imaging is nonthreatening.

“Obviously, the main goals for all professional searchers is: what is your target?” Cunningham told me. “But it can be just as important to understand distracting or non-target information... That can actually play a larger role in whether you can find things successfully or efficiently.”

It remains to be seen how this mental filtering can help people in everyday situations. Do you end up getting through checking email faster because you’re already primed to ignore mass mailings from, say, political candidates and clothing stores? (Unclear. Probably you should just unsubscribe already.)

“The dark side of attention, the other side of attention, is this two-part process,” Cunningham said. “Every time you tell someone to pay attention, you’re also telling them something that’s a little more implicit, which is: ‘I want you to ignore everyone else or everything else around the room.’”

Cunningham offers the example of a crowded office, where someone might be trying to pay attention to a phone call, and therefore has to ignore the sound of people’s voices in the same room. “Is your brain actually representing all those other people, or is it just trying to activate the signal that’s [the voice on the telephone]? What does that suppression process look like? Do I create a general pool of things I should ignore, or do I explicitly say, ‘I am going to ignore Bob and Cari.’ The answer is: We don’t know. And we want to find out.”

In the meantime, you’re still not thinking about polar bears, right?