Image via Dream Designs/Shutterstock.com

Scientists Find Possible Cause of Bipolar Disorder

NIH-funded genomic advances help unravel the mysteries of bipolar disorder.

We know that heredity, along with environment, plays an important role in many mental illnesses. For example, studies have revealed that if one identical twin has bipolar disorder, the chance of the other being affected is about 60%. There are similar observations for autism, schizophrenia, and major depression. But finding the genes that predispose to these conditions has proven very tricky.

Now, an NIH-funded team at Baylor College of Medicine has demonstrated for the first time that extra copies of a gene that codes for a protein called Shank3 can cause manic episodes similar to those seen in some types of bipolar disorder. The researchers initially tested their hypothesis in mice and then, building upon those findings, went on to find extra copies of the SHANK3 gene in two human patients—one with seizures and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and another with seizures and bipolar disorder.

Before we delve deeper, let me give you a bit of background. When people suffer from bipolar disorder, also known as manic-depressive illness, their mood swings between two extremes: mania and depression. These mood swings go well beyond the regular ups and downs of daily life. They are disabling. During manic episodes, people may report feeling “wired,” jumpy, or overly energetic and happy. They may speak quickly, have difficulty focusing, become unrealistically ambitious, make hasty decisions, and engage in high-risk activities and behaviors. If untreated, mania interferes with their family, school, and work life. At the other extreme, the depressive components of bipolar illness can be profound, with extreme sadness, hopelessness, and a serious risk of suicide.

Previous studies have found that people who share a region of DNA that contains extra copies of the SHANK3 gene, along with some other genes, tend to be hyperactive and suffer from seizures, along with a host of other issues. But it’s never been determined whether simply having extra copies of the SHANK3 gene—and thereby unusually high levels of the Shank3 protein—is enough to cause mania.

To find out, the Baylor team created a strain of genetically engineered mice that produces 50% more Shank3 protein than normal mice. These transgenic mice turned out to be hyperactive and troubled by seizures. What’s more, they moved at a faster pace, were more sensitive to sound, had unusual sleep-wake cycles, and displayed increases in appetite—all things characteristic of manic behavior in humans.

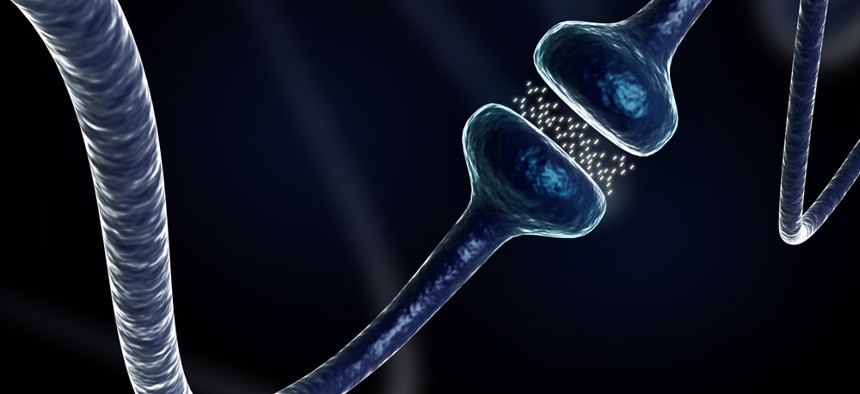

The researchers then explored how extra amounts of Shank3 protein wreak havoc inside the brain. In lab studies that examined brain cells, called neurons, derived from the Shank3 mice, the researchers found that higher-than-normal levels of Shank3 boosted the number of dendritic spines on the neurons. That’s a key finding, because dendritic spines are structures that neurons use to receive excitatory signals.

Next came studies looking at the effects of two mood-stabilizing drugs commonly prescribed for bipolar disorder. In mouse studies, the researchers first tested whether the drug lithium reversed the effects of too much Shank3. It didn’t. That’s not particularly surprising, given that we know that lithium also doesn’t help a significant subset of humans with bipolar disorder.

The researchers then gave another drug often used for bipolar disorder, valproate, to the Shank3 mice. It worked—reversing the animals’ hyperactivity and sound sensitivity, as well as correcting abnormal signaling activity in the brain.

All of this—the latest study and the future work it will fuel—adds up to encouraging news for the more than 5 million U.S. adults affected by bipolar disorder. It also provides yet another compelling example of how basic research aimed at understanding fundamental biology may lead to more precise and effective ways to treat complex medical conditions.