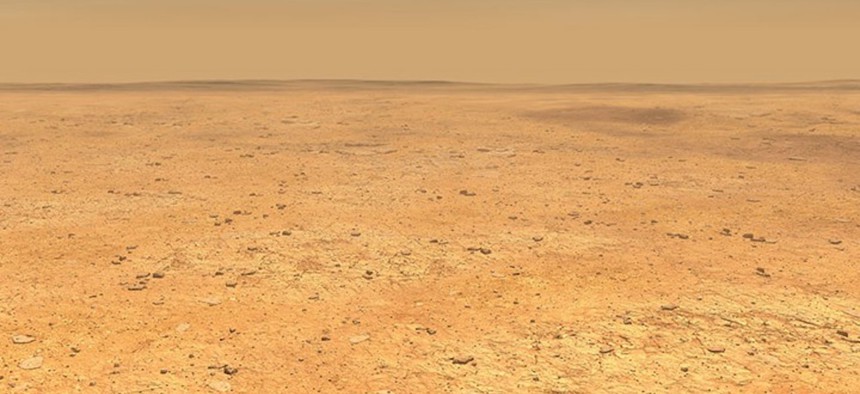

NASA / JPL-CALTECH

A Robot Has Been Stuck on Mars for Months

NASA will conduct a delicate rescue mission to free a probe trapped just inches below the Red Planet’s surface.

Sue Smrekar wishes she could be on Mars right now.

Specifically, on Elysium Planitia, a smooth plain in the planet’s northern hemisphere, where a NASA spacecraft called InSight resides. InSight touched down on the surface last November and used its robotic arm and five-fingered hand to unpack. The cider-colored ground was soon littered with scientific instruments, like a well-arranged picnic spread. Once the spacecraft had settled in by late February, one of the instruments, a probe designed to burrow deep into the Martian ground, started hammering away.

Then, suddenly, it stopped. After traveling 300 million miles to Mars, the probe got stuck just inches below the surface. It has remain wedged there since, but NASA hopes a delicate rescue operation could soon free it.

“We’d hoped to be well into the ground by now,” Smrekar, the deputy principal investigator of the InSight mission at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, told me.

NASA dispatched InSight to Mars to study the interior of the red planet, which, even after many decades of missions, scientists still know little about. The mission would help scientists determine what Mars is like on the inside, and whether its guts resemble another rocky planet—our own.

The probe, made up of a spike and a sensor-studded tether, is designed to burrow nearly 16 feet into the surface. That’s deeper than previous instruments have gone “on any other planet, moon, or asteroid,” according to NASA (excluding Earth, of course). The tether was supposed to follow the spike down and measure the heat coming from the planet’s interior. The machine only made it 12 inches. “It initially was making fabulous progress, and then just abruptly stopped moving forward,” Smrekar said.

The team was stunned. Maybe the instrument had hit a rock, they thought. The scientists and engineers of the InSight mission had prepared for such a scenario; during testing before launch, the heat probe, which they call “the mole,” had shown it could break some rocks and even maneuver around others. The team instructed the mole to keep hammering, in case the force shattered the obstacle, but that didn’t help.

Scientists now suspect another culprit: the Martian soil itself. As the probe hammered, loose dirt was supposed to swirl around it, providing friction for its back-and-forth movements. But the soil might have clumped together instead and moved away from the instrument. Eventually, a moat of empty space could have emerged between them. “Some friction is essential for the mechanism to work, as the recoil produced by the mechanism during hammering needs to be absorbed,” said Matthias Grott, a scientist at the German Aerospace Center’s Institute of Planetary Research, which built the instrument for NASA. Without that friction, the probe just bounces in place.

Spacecraft have never encountered such difficult soil on Mars before, and the probe wasn’t designed to handle it. Scientists have since recreated these conditions back on Earth, with a replica of the heat probe and stickier sand; the experiment, in an outcome that is both reassuring and disheartening, showed the probe could indeed become stuck like this.

The circumstances are certainly unexpected, but not insurmountable. The team could generate some friction by using the InSight spacecraft’s robotic hand to scoop some soil into the space around the probe or apply pressure to the ground.

If only they could see anything.

InSight’s cameras can take pictures of its surroundings to send home, but they don’t have eyes on the problem. The probe arrived in a cylindrical case that hold it steady until it drilled itself free, but only made it out so far before becoming stuck. The case now blocks InSight’s view of the probe and the surrounding regolith.

So the InSight team has devised a rather clever plan. They will use the robotic arm to lift the case, little by little, to get a better look at the probe beneath.

It’s a risky operation. If they end up pulling the probe out of the ground, they can’t stick it back in. InSight’s robotic arm was designed to clutch the case, not handle the probe. So they will command the spacecraft to move carefully, like a stop-motion animator adjusting clay after every take: Lift a little, back off, take a picture, beam it home. The spacecraft is scheduled to attempt this maneuver for the first time tomorrow, raising the case a mere five inches. More attempts are planned for next week. With a better view, the team can confirm the problem and determine a fix.

Here’s a look at the robotic hand unfurling in preparation for the procedure, seen in shadows across the Martian surface:

For now, mission staff is trying to look on the bright side. InSight’s other instruments are working fine; in April, the seismometer detected, for the first time in history, a Marsquake. It has even pitched in to provide data about the probe’s unlucky surroundings, recording the rumbling that resulted from its failed hammering attempts. And besides, it’s better to have a jammed probe now, when one end of it is still sticking out of the ground and within reach, than after it goes subterranean. “If the mole were in the ground and hit a rock, there’s nothing we could do to help,” said Troy Hudson, a scientist and engineer at JPL. “The arm isn’t powerful enough to excavate it.”

And the team has already learned something new about the Martian landscape. “If you asked somebody, ‘What’s the soil on Earth like?’ Well, it depends greatly on where you are. Is it beach sand on Hawaii or loamy soil in Arkansas?” Hudson said. “Mars is a lot more homogenous than Earth, but it’s still an entire planet and soil types are going to be different in different locations.”

InSight’s heat probe is not yet lost, but if the rescue mission goes south, it won’t be the first NASA spacecraft to succumb to Mars and its surprises. In 2009, the Spirit rover became trapped in a sandpit and was unable to reach a slope from which to charge its solar-powered panels. Last year, Opportunity, Spirit’s sister rover, met a similar fate when a dust storm of unprecedented size swept across the planet and blocked sunlight from reaching its panels.

Any time a mission doesn’t go exactly as planned, there are scientists and engineers worrying and troubleshooting and pacing back home, wishing they could be there to help. Before Opportunity was declared dead, Keri Bean, a science planner on the mission, told me she dreamt about saving it. “Sometimes I’ll have dreams in the middle of the night. I’m standing there on Mars next to her, and wiping the dust off her lenses,” she said.

The reality is far more frustrating. This week, at a meeting of InSight scientists in Paris, Smrekar listened to a colleague describe a recent test with a replica of the heat probe. It had rained, and a box of sand, playing the role of Martian soil, became damp and sticky. The instrument couldn’t move, so the scientist stuck a finger in the sand, wiggled it around, and made some room. That’s all it took—on Earth. On Mars, NASA needs a breakthrough.