But before NASA sends humans to Mars, it’s going to send them back to the moon, according to the Trump administration’s space policy. Just don’t expect any bumper stickers for that. At least not yet.

“Ultimately we want to have the ability to put humans on the surface of the moon,” Jim Bridenstine, the NASA administrator, said this week. “I don’t have a time frame for that at this point.”

Bridenstine outlined the space agency’s lunar ambitions, among other plans, in an hour-long round table with a dozen reporters on Wednesday. The meeting marked the administrator’s first formal sit-down with members of the press since he was sworn into the office in April after a contentious nomination process.

Bridenstine does have a time frame for moon activities for the next several years. “We want to get robots and landers on the surface of the moon aggressively—2019,” he said. “Definitely by 2020.”

These machines would be built by commercial space companies, and not NASA. Bridenstine warned the approach may lead to some losses.

“It’s important to remember that we’re going fast and we’re going commercial, and that some will probably fail,” he said. “If we have a dozen companies participate and make the effort and get close, that’s great. If, of those—let’s say half a dozen companies—if three of them are successful, that’s a great win. If three others aren’t successful, but have achievements that NASA can then take advantage of, it’s still a win. We want to get to the surface of the moon as soon as possible, robotically, with small landers, commercially.”

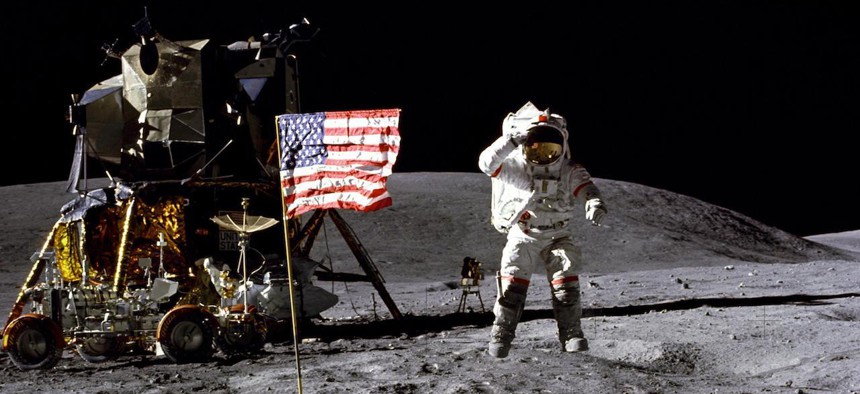

After that, NASA will send spacecraft capable of burrowing beneath the lunar surface and excavating material. And then, at some point, the space agency will bring astronauts back to the moon, a place humans haven’t visited since 1972.

The lack of a bumper sticker–worthy target may be disappointing, particularly for lunar scientists and advocates who have been craving a renewed emphasis on the moon. Public deadlines for the space program can be beneficial in a number of ways; they can impose some sense of internal discipline, unite multiple corners of the scientific community, and rally excitement and inspiration from the public that’s paying for it.

But deadlines in space exploration are also notoriously fickle. They stall, they shift, they get tossed out by one president and reinstalled by another. And in the meantime, little actually gets done to reach them.

For the last eight years, NASA has advertised an American journey to Mars. Various missions into deep space, whether they have been related to this goal or not, have been touted as a step toward sending humans to Mars. But firm time lines, let alone concrete plans, have not emerged. Nasa officials frequently appear on Capitol Hill to tell lawmakers that the agency needs more resources and more direction before it can even begin to plot out the specifics of a Mars mission.

Now, as the White House pushes NASA toward the moon, the American space program may find itself embarking on a similar, years-long journey of public promotion and discussion, and no action. Perhaps a moon target seems more doable because, well, we’ve been there before. But the United States no longer has the technology to put complex robotic missions on the moon, let alone people. It doesn’t have the Apollo-era drive, fueled by an ideological war, that put men on the moon in a fairly short timespan, either.

The United States has spent nearly a decade talking about Mars but has taken few concrete steps to fund and develop an actual mission. Are we about to spend years doing the same for the moon?

President Trump’s moon-first policy began to take shape as soon as he took office. The plans mark a significant shift from the space policies of former President Barack Obama, whose administration put NASA on a very public journey to Mars. Obama’s space policy involved plans for human activities on the moon, but these efforts were presented as testing operations for a mission to Mars, and not the foundations for a long-term outpost on the moon. “It’s a 180-degree shift from no moon to moon first,” John Logsdon, a space-policy expert and a historian, told me last year.

In February 2017, leaked internal documents, prepared by the presidential transition team assigned to NASA, suggested the president set the country on a path to return Americans to the moon, or at least to orbit, by as early as 2020. Rumors of a shift in mission swirled for months.

In December of that year, the rumors became policy. President Trump signed a directive that called for a return to the moon, carried out by the U.S. government with help from private-sector companies.“It marks a first step in returning American astronauts to the moon for the first time since 1972, for long-term exploration and use,” the president said. “This time, we will not only plant our flag and leave our footprints—we will establish a foundation for an eventual mission to Mars, and perhaps someday, to many worlds beyond.”

This year, the Trump administration presented some specifics to these moon-focused exploration ambitions. In the president’s budget proposal for the fiscal year 2019, released in February, the administration renamed an Obama-era proposal for a platform in low-Earth orbit that astronauts would use as way station on the way to Mars. The Deep Space Gateway would be called the Lunar Orbital Platform-Gateway, and the administration wants it to be ready for human habitation by 2023.

Last month, Wilbur Ross, the Commerce secretary, said the moon will become “a type of gas station,” a pit stop for rocket ships to refuel before hurtling deeper into space, “a lot sooner” than in the next decade.

A moon-first policy has not meant that all moon-focused programs at NASA are safe. In April, the agency canceled its only planned robotic mission to the surface of the moon. The Resource Prospector, a small rover nearly a decade in development, was supposed to look for and dig up material from the moon’s poles, where previous missions have shown water ice exists. The decision to scrap the project likely pre-dated Bridenstine, but as the new face of NASA, he had to answer for it. A group of lunar scientists, engineers, and others in the field sent Bridenstine a letter protesting the cancellation. “We’re committed to lunar exploration,” Bridenstine tweeted in response. “Resource Prospector instruments will go forward in an expanded lunar surface campaign. More landers. More science. More exploration. More prospectors. More commercial partners. Ad astra!” To the stars, but to the moon first, and with less in-house technology.

The Mars bumper stickers came up at Wednesday’s roundtable with Bridenstine. On Capitol Hill, the stickers come from Ed Perlmutter, a Democratic congressman from Colorado who was, just six weeks ago, Bridenstine’s colleague. Perlmutter’s staff designed the stickers themselves, his office once told me, and the congressman always carries a few with him to hand out “to whoever shows the slightest interest,” his spokesperson said. Perlmutter picked 2033 because, in that year, the orbits of Earth and Mars will bring the planets close enough for a fairly quick journey between them, about a year-and-a-half round-trip, instead of two or three years.

A reporter asked Bridenstine whether the administrator could say, once and for all, whether Perlmutter’s goal is attainable or unrealistic.

“I think it’s a great target—and I’ll leave it at that,” Bridenstine said with a smile. “But if I can make Ed Perlmutter happy, that’s my goal. And you can put in the story that I love Ed Perlmutter.”