USDA would likely send home a higher percentage of its workers than it had planned to in September, because it is no longer in the middle of wild fire season. Kari Greer/U.S. Forest Service file photo

Some Agencies' Shutdown Furlough Plans Have Changed Dramatically in Past 2 Years

Many feds sent home in 2013 would face a different fate this year if agencies are forced to close.

As Congress attempts to reach an 11th hour deal to avoid a government shutdown, federal agencies are dusting off their contingency plans and readying for the scenario in which Congress fails to act.

Luckily for them and their cleaning service contract budgets, little dust should have accumulated, as every federal agency detailed those plans just 10 weeks ago. Also still fresh in the minds of much of the federal workforce is the 16-day shutdown that occurred in October 2013. Those employees should not, however, take for granted that their shutdown status in either of those plans would apply to an appropriations lapse later this month.

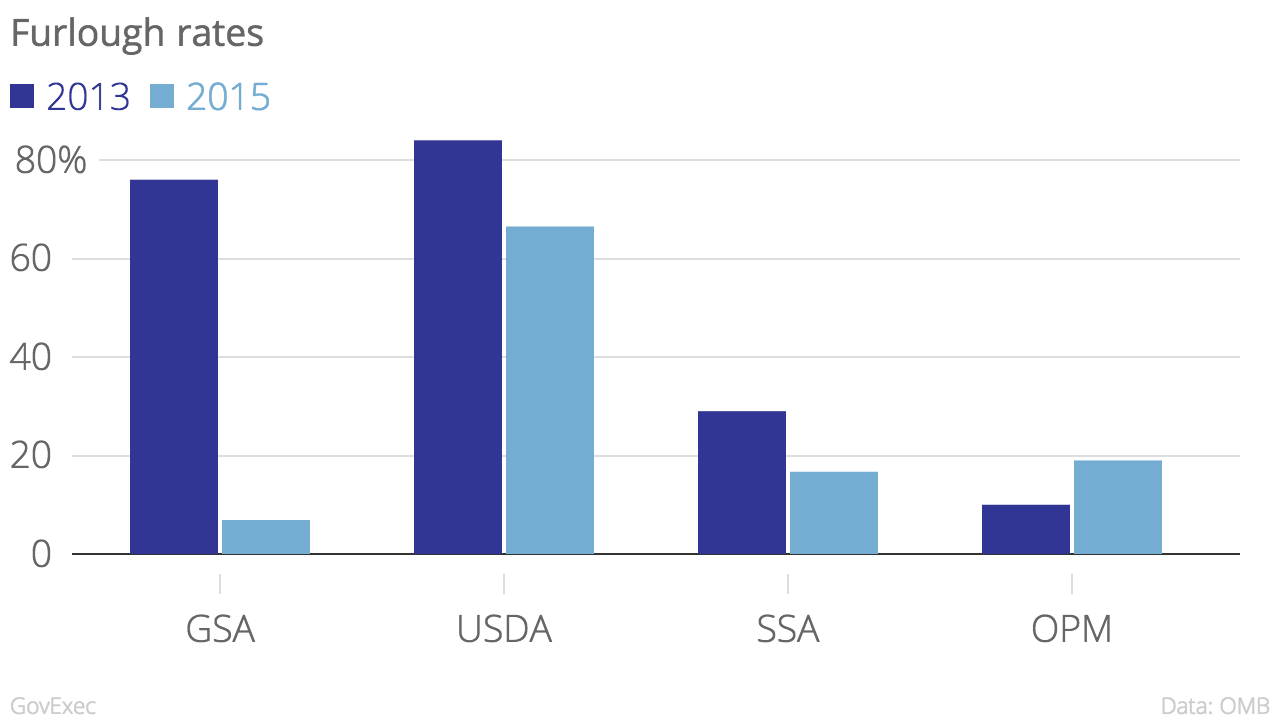

Several agencies changed their furlough rates from their 2013 plans to their 2015 plans by significant margins, while others have said their plans from September are already out of date.

The General Services Administration decreased the number of employees it would furlough today from the number it forced to take leave without pay two years ago; in 2013, GSA sent home more than three-quarters of its roughly 11,000-person workforce. This year, the agency would furlough just 7 percent of its employees, among the lowest rates of any in the executive branch.

GSA has clarified its authorities since 2013, the agency said, and determined employees whose salaries were paid by the Acquisition Services Fund, the Federal Buildings Fund and the Working Capital Fund were exempt from shutdown procedures and their operations were allowed to continue in accordance with shutdown guidance. Those employees make up a majority of GSA’s workforce, thus accounting for the major shift in furlough policy.

The Agriculture Department also significantly increased the percentage of its workforce it would force to work without immediate pay during a shutdown, but said the majority of the gap was due to the evolving nature of its mission. In 2013, USDA furloughed 84 percent of its workforce of nearly 100,000; this past September, the agency said it would send home two-thirds of its employees. A spokesman explained that 10 weeks ago, USDA was in the midst of fighting one of the worst wildfires in history. Its seasonal firefighters are not subject to shutdown furloughs, the spokesman said.

In 2013, the wildfire season was not as strong, meaning there were fewer seasonal employees and a high percentage of workers were furloughed. Additionally, because the wildfire season has mostly passed, the department would likely send home a higher rate of its workers if a shutdown occurs this month than it had planned for in September.

The Social Security Administration furloughed 29 percent of its 65,000 employees in 2013, but planned in September to send home just 17 percent of its workforce. SSA has long represented the fluidity of shutdown contingency plans; just three days into the 1995 appropriations lapse, the agency recalled 50,000 workers needed to deliver benefits. In its initial planning, SSA had not properly accounted for its legal obligation to distribute earned government checks.

An SSA spokeswoman declined to explain why SSA’s furlough rate changed in the last two years.

The Office of Personnel Management, responsible for setting many of the policies for employees on furlough status, was the lone large agency to actually increase by a significant margin the percent of its workforce subject to mandatory unpaid leave. In 2013, the human resources agency furloughed just one in 10 of its employees; in September, it planned to send home nearly one in five.

Sam Schumach, an OPM spokesman, pointed to the 2014 layoffs at the agency’s Human Resources Solutions office as the most significant factor in the furlough rate changing. HRS is self funded by agencies paying for its consultants to offer HR expertise, and such operations are exempted from furloughs. Because those employees make up a smaller percentage of the overall OPM workforce, a larger portion of the agency’s employees would face furloughs this year.

While some significant changes would likely occur in the event of a shutdown, most agencies' furlough rates stayed relatively flat between 2013 and 2015. All told, more than 860,000 federal workers would be sent home, while about 1.3 million would have to show up to work and receive delayed paychecks.

As was apparent both in the 1990s and in 2013 when the Defense Department recalled most of the 400,000 civilians it initially furloughed, the furlough rates are not set in stone and can fluctuate based on emergency situations, the length of the funding lapse or various acts of Congress.

For example, the Commerce Department has noted in its most recent contingency plan that all 12,000 Patent and Trademark Office workers would be exempt during a shutdown and would report to work. If the government remained closed for more than four weeks, however, existing funds would dry up and furloughs would begin. The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation would face a similar situation. The Federal Emergency Management Agency in 2013 recalled some employees to deal with an anticipated tropical storm

Federal agencies are currently operating on a continuing resolution that is set to expire Dec. 11. Lawmakers appear set on buying a few more days to avoid a shutdown while they continue to negotiate a longer-term omnibus appropriations bill.