Flickr user Gage Skidmore

GOP Pushes HHS Appraisal of Health Reform Proposal Rather Than Waiting for CBO's Evaluation

In an 11th hour push to repeal Obamacare, Republicans are leaning on a murky analysis that supports their plan.

The Department of Health and Human Services does a great number of things, but providing authoritative analysis of legislation isn’t usually one of them.

That task is left instead to the Congressional Budget Office, the independent agency lawmakers typically rely on to score each and every bill. Yet when it comes to health care, Republicans seem willing to put their trust in the evaluation that’s best for them, regardless of who prepared it—and dismiss assessments that will only make Obamacare repeal harder.

As the prospects for passing a repeal-and-replace law have grown dimmer over recent weeks, Republicans have increasingly divorced themselves from the CBO, which has repeatedly assigned negative scores to the party’s plans. Instead, the GOP has opted for a much more insulated approach to mathematics. Most recently, lawmakers seized on a “preliminary draft” of HHS’s appraisal of a controversial amendment to the Senate’s Better Care Reconciliation Act.

The amendment in question is one proposed by Texas Senator Ted Cruz. It would allow Obamacare insurers to provide additional plans off of the exchanges that would also qualify for tax credits and wouldn’t have to comply with Obamacare regulations. Insurance-industry predictions have found that those provisions—along with the BCRA’s base measures that allow less comprehensive plans, repeal the individual mandate and Medicaid expansion, and provide less generous tax credits—would essentially splinter Obamacare risk pools and create the conditions for a “death spiral.”

Their suspicions have yet to be confirmed by the CBO, because the Cruz amendment was left out of its most recent score of the BCRA. Although the amendment was submitted for a score last week, the agency needs more time to evaluate it, thanks to both the substantial changes it’d make to the way exchanges work, and the sophisticated simulations those changes would entail. But Senate Republicans—facing defections from both moderates and conservatives in the conference—might not have that kind of time.

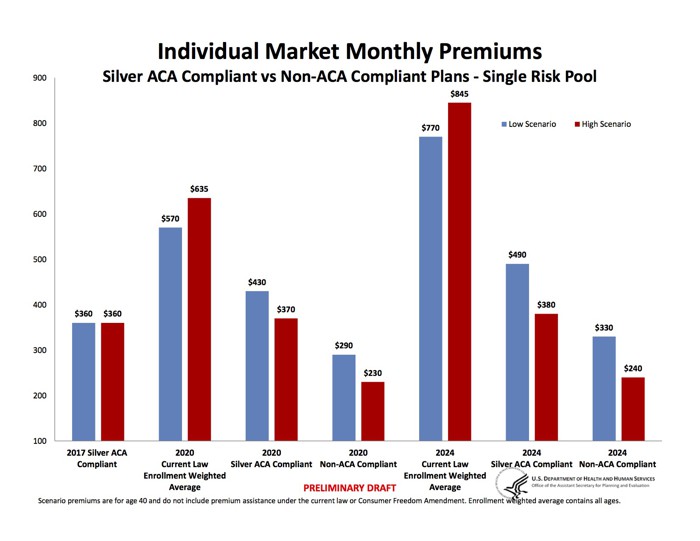

Perhaps uncoincidentally, the HHS’s draft models of the Cruz amendment reached the internet just before the latest CBO score, giving lawmakers another way to ignore its assessment. Published Wednesday by the Washington Examiner, the models paint a rather favorable picture for the package. While even HHS concedes the Cruz amendment could create separate risk pools, its analysis predicts that dynamic would actually cover more people than the current law does and would perhaps lower premiums:

These predictions have come under fire from health-policy experts for a number of reasons. First, the HHS analysis does not apply the Cruz amendment to the BCRA, but to a modified ACA, with both its tax credits and insurance mandate in place. Both of those, of course, help pay for risky patients and improve the health of the exchange markets, and would mitigate the effects of Cruz’s measure overall. Also in its evaluation, HHS “assume[s] that an adequate number of issuers offer at least one bronze, silver, and gold qualified health plan.” That assumption seems dubious given: insurers’ own warnings about the senator’s amendment, the current precariousness of exchange offerings, and the CBO’s findings that removing the mandate and reducing tax credits could leave millions of Americans living in places with no exchange offerings at all.

As Vox’s Sarah Kliff points out, the report’s premium models benefit from some rather obvious misdirection. In the chart above, the scenario under current law is presumably a weighted average of the people in exchanges, where the average age is 48 years old. But the chart uses an age-40 benchmark for predictions under the Cruz amendment. Insurance for 40-year-olds is simply cheaper than it is for 48-year-olds.

Additionally, as the left-leaning Center on Budget and Policy Priorities indicates, the skimpy “freedom” options allowed under Cruz’s amendment would have $12,000 deductibles. It’s hard to see many Americans signing up for such a plan without there being a mandate to do so. As the most recent CBO score reportstates about other low-premium plans, that deductible is higher than the ACA’s out-of-pocket limits, and under it, “many people with low income would not purchase any plan even if it had very low premiums.”

The biggest problem with the preliminary report is that its methods are opaque and the assumptions that went into the charts are largely indecipherable. Experts have focused on the “proprietary elasticity estimates”—reportedly created by consulting firm McKinsey—as a special black box because all of the assumptions on how people would actually respond to insurance are wrapped up within it. But some murkiness is more fundamental: The terms on charts aren’t clearly laid out; there’s no discussion of any of the decisions authors made about future premiums under Obamacare or implications of the report’s results; and the “limitations” section, which would ordinarily describe how useful the report’s results are in the real world, doesn’t actually list any limitations.

Compare that with the CBO’s typical analyses: The basic framework of its health-care simulations is known, and each report building on those simulations carefully details its working assumptions.

The new HHS report is inscrutable and sparse even when compared with the department’s previous analyses of health-care laws and regulations. It’s not unheard of for HHS and its constituent agencies to release regulatory-impact analyses that supplement—and sometimes contradict—CBO scores. In fact, that’s a core job of certain offices, and the rich combination of data from multiple authorities with deep expertise and analytical power sharpens policy. But this preliminary draft is just not useful in its current form as a policy analysis, let alone as something that could approximate a CBO score.

Yet, that seems to be how Republicans are trying to use it. Senators Ron Johnsonof Wisconsin and John Thune of South Dakota have floated the unprecedented idea of using the HHS score alone, or in concert with an evaluation from the White House Office of Management and Budget, as a substitute for the CBO’s score. But OMB Director Mick Mulvaney has stated point-blank—of his own office—that “we admit we don’t know how to count coverage.”

The involvement of any White House-aligned parties in the scoring process—if it’s even allowed under Senate rules—would also invite skepticism. Can, for example, a department run by HHS Secretary Tom Price, one of the leading opponents of Obamacare since its inception and a frequent CBO critic, really be counted on to make an unbiased assessment? Especially if it doesn’t reveal its methods?

Republicans have ignored those concerns in favor of agitation against the CBO. A June Fox News op-ed from North Carolina Representative Robert Pittenger claimsthe CBO “only provides unsupported conclusions, as it is based on highly questionable predictions.” The president’s aides called recent CBO scores “little more than fake news” in a Washington Post op-ed, and the White House has also released videos on social media attacking the agency’s conclusions. House Speaker Paul Ryan attempted in March to preempt an earlier CBO score with a presentation of his own analysis, and on Thursday he called the most recent CBO report “bogus.”

It seems clear that the party is positioning itself to be free of the agency’s continually gloomy forecasts for its health policies. But on the BCRA, those forecasts have been—more often than not—generally comparable to those compiled by groups across the health-care industry, as well as by expert consultants and think tanks. Instead of engaging with those analyses and building policy that can make the numbers work, Republicans are opting to embrace a post-factual opaqueness. It may serve their political efforts well, but it won’t do much for reality when the resulting policies actually kick in.

(Top image via Flickr user Gage Skidmore)

NEXT STORY: The War on the Freedom of Information Act