Trump and Kim Will Talk After All—But About What?

The on-again, off-again meeting between Donald Trump and Kim Jong Un is apparently happening. But there's little evidence that North Korea actually wants to denuclearize.

On Friday, after the highest-ranking North Korean official to visit the U.S. in 18 years hand-delivered him a letter from Kim Jong Un, Donald Trump declared that his once-canceled summit with North Korea’s leader was back on schedule for June 12 in Singapore. “We’re going to start a process,” the president said. “I think we would be making a big mistake if we didn’t have it.”

Trump may have been uncharacteristically playing down expectations because, if there’s one lesson to emerge from the frenzied efforts to salvage the Trump-Kim summit in recent days, it’s that the devil is in the details of “denuclearization.” And Kim’s letter to Trump is reportedly quite short on details. It raises real questions about what the two leaders actually hope to accomplish.

The letter “expresses the North Korean leader’s interest in meeting without making any significant concessions or threats,” The Wall Street Journal reports, according to an unnamed foreign official familiar with the contents. Trump called it “a very interesting letter.”

With just over a week to go until June 12, Kim’s government has—publicly at least—offered strikingly little evidence that it is prepared to give up its nuclear weapons. North Korean officials regularly express interest in pursuing the “denuclearization of the Korean peninsula.” But since the United States withdrewits tactical nuclear weapons from South Korea in the early 1990s, North Korea’s vague formulation only makes sense if it includes a demand for the United States to stop protecting South Korea with the American nuclear-weapons arsenal and nuclear-capable military assets, to withdraw U.S. troops from Korea, or to end the military alliance altogether.

“North Korea hasn’t really committed to anything” on denuclearization or specified a time period for achieving it, Chun Yung Woo, a former South Korean national-security adviser, told me in Seoul in May. If Kim Jong Un has made any commitment, it’s to “the goal of denuclearization,” not to denuclearization itself, added Chun, who led his country’s delegation to the six-party nuclear talks with North Korea in the 2000s. “I have been hearing this all the time over the past 20 years—even from the five nuclear-weapons states,” who laud the “goal of a world free of nuclear weapons. … [Kim] is thinking of a nuclear-free Korean peninsula in terms of a nuclear-free world. This is a long-term, distant aspiration of humanity.”

Even if North Korea agrees to roll back its nuclear program, it favors not the Trump administration’s preferred “one-shot denuclearization” but a “step-by-step” approach in which incremental dismantlement is traded for commensurate economic, security, and political concessions from the United States and other countries, said Kim Hyun Wook, a professor at the Korea National Diplomatic Academy, which is affiliated with South Korea’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs. These concessions could include sanctions relief, economic aid and investment, a formal declaration to end the Korean War, the normalization of relations between the United States and North Korea, and a nonaggression pact or peace treaty among the parties to the conflict on the peninsula.

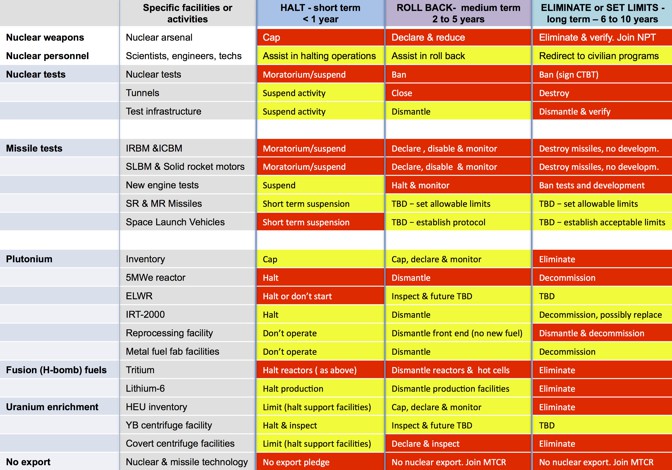

Such a phased approach might take a decade or more to implement given that North Korea’s sophisticated nuclear-weapons arsenal took 25 years to build up and is comprised of dozens of sites, hundreds of buildings, and thousands of people, according to a recent estimate by Stanford researchers (including Siegfried Hecker, a nuclear-security expert who has examined North Korea’s nuclear facilities several times). The researchers’ roadmap for denuclearizing North Korea illustrates just how devilishly complicated an undertaking this could be:

Siegfried Hecker / Stanford Center for International Security and Cooperation

North Korea wants to talk to the United States about “a much more limited set of concessions that actually represent kind of the opposite of denuclearization,” the arms-control expert Jeffrey Lewis recently noted. “What the North Koreans are bargaining for is recognition and they’re trying to set the terms under which we will accept their nuclear arsenal. Like, ‘Well, what if we don’t test [nuclear weapons or long-range missiles]?’ … What if we promise not to export [nuclear weapons or materials]? What if we have a slightly nicer declaratory policy [regarding the circumstances in which North Korea would use nuclear weapons]? If all of those things get done, would you be willing to accept a vague aspiration for denuclearization without [us] actually giving up any weapons?’”

Kim “will try to hold as much [of his] nuclear arsenal as possible for as long as possible,” Chun said. If he makes surprisingly big concessions on his nuclear weapons and enrichment capabilities, Chun reasoned, it will be because as a young ruler for life he feels confident in his ability to reconstitute his nuclear program in the future, when the term-limited American and South Korean presidents are long out of office and North Korea has already reaped the benefits from all the economic assistance and security assurances it received in return.

The U.S. and South Korean governments include their share of cynics and skeptics too. NBC News reported this week that a CIA assessment circulated in May “concluded that North Korea does not intend to give up its nuclear weapons any time soon,” quoting one anonymous intelligence official who read the analysis as saying that “everybody knows they are not going to denuclearize.”

On a background call with reporters last Thursday, shortly after Trump canceled his summit with Kim, a senior White House official raised doubts about whether North Korea had truly disabled a nuclear-test site it claimed to have demolished earlier in the week. The official incredulously compared North Korea’s promiseafter its summit with South Korea in April to realize “through complete denuclearization, a nuclear-free Korean Peninsula,” with a furious statementfrom a North Korean official that week proclaiming North Korea a “nuclear-weapon state” and rejecting the U.S. policy that the North agree to “complete, verifiable, and irreversible denuclearization,” or CVID. “How could [North Korea] declare that it is moving forward with the goal of complete denuclearization but object to denuclearization in a statement two weeks later?” the official asked. “It’s a head-scratcher.”

The South Korean government—whose President Moon Jae In advocates diplomacy with North Korea and has played a pivotal role in bringing Trump and Kim to the threshold of a summit—has trumpeted Kim Jong Un’s willingness to denuclearize with far more confidence than the U.S. government. But here too, there are notable doubts. When Moon was asked at a press conference on Sunday whether Kim is ready to embark on the CVID-style denuclearization that the U.S. insists on, the South Korean leader evaded the question. “The U.S. and North Korea need to engage in working-level talks to confirm their intentions on denuclearization,” he said.

A few days later, South Korea’s unification minister admitted that “the differences in stances between North Korea and the U.S. remain quite significant” but grasped at a sliver of hope by adding that “it would not be impossible” to “narrow the gap and find common ground.” When I asked a senior South Korean official last month whether North Korea was committed to completely denuclearization, the official responded, “That’s a big question. Skepticism is always healthy, but I am optimistic. … We’re not giving rewards until we see concrete actions and assurance of complete denuclearization.”

The extent to which North Korea accepts CVID “depends on what kinds of terms, rewards Trump will give to” Kim Jong Un, Chung In Moon, a special adviser to the South Korean president for foreign affairs and national security, told me in May. The North Korean nuclear issue “should be based on the principle of reciprocal exchanges. The U.S. cannot make North Korea surrender. We all know what we want from North Korea. But we do not know what North Korea wants [and] what Trump can give to North Korea.”

The North Korean ideal of a nuclear-free Korean peninsula and the American ideal of a speedy, wholesale dismemberment of the North Korean program, could be thought of simply as opening positions ahead of the painful compromises each side will make in negotiations. “Think of it like … a poker game,” James Lindsay of the Council on Foreign Relations recently suggested. “We’re not really sure what hands each player holds and how they intend to play, and you’re only going to really be able to see it as the cards get laid down.” The Singapore summit is an opportunity to lay some cards down. If Trump and Kim “agree upon the formula of denuclearization, then I think it’s a success,” Kim Hyun Wook told me.

But the glaring question this week is whether the United States and North Korea are so far apart from one another that even a basic formula is out of reach. Before bringing Kim Yong Chul, the visiting North Korean official, to Washington on Friday to meet with Trump, U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo told reporters in New York that he believes the North Koreans “are contemplating a path forward where they can make a strategic shift, one that their country has not been prepared to make before.” If the North Koreans are really preparing to make such a shift, they’re staying remarkably tight-lipped about it.