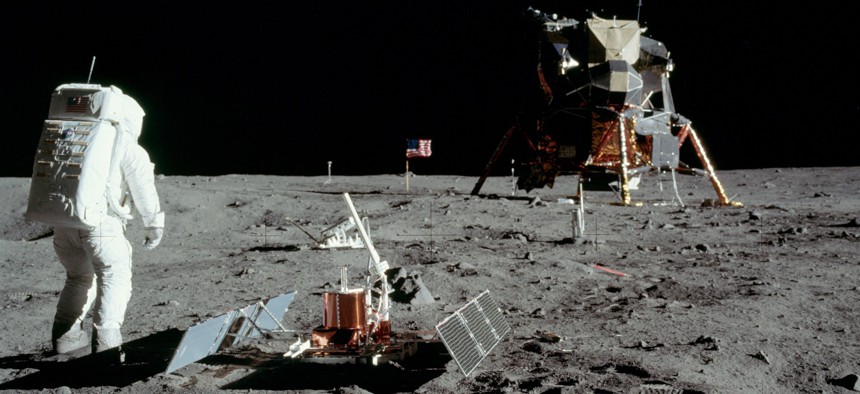

Astronaut Buzz Aldrin is shown on the surface of the moon during the Apollo 11 extravehicular activity. Neil Armstrong/NASA

Trump's NASA Pivot

His administration has made the moon a destination, not just a pit stop, on the way to Mars.

Rumors that the Trump administration was more interested in the moon than Mars began circulating days after the inauguration. Leaked memos published in February revealed the president’s advisers wanted NASA to send astronauts there by 2020, one part in a bigger plan to focus on activities near Earth rather than missions deeper in the solar system. Vice President Mike Pence spoke vaguely of a return to the moon in a speech in July. In September, the administration nominated a NASA chief who extolled the construction of lunar outposts. All signs pointed to a significant shift in the country’s Mars-focused space agenda of the last seven years.

This week, the Trump administration made it official.

“We will return NASA astronauts to the moon—not only to leave behind footprints and flags, but to build the foundation we need to send Americans to Mars and beyond,” Pence said Thursday at the inaugural meeting of the National Space Council, an advisory body his administration recently revived.

The vice president’s comments marked a pivot from Barack Obama’s directive for a “Journey to Mars,” established in 2010, and harkens to the aspirations set forth by the George W. Bush administration. The Obama administration had maintained that some kind of human activity in cislunar space—the region between the Earth and the moon—was necessary to test technology for a mission to Mars, but the efforts would amount to a pit stop, not a destination. While Pence did not provide details on what kind of “foundation” Americans would build on the moon, the new direction was clear: Americans should be spending more time in their cosmic backyard before flying off into the solar system.

“It’s a 180-degree shift from no moon to moon first,” said John Logsdon, a space-policy expert and former director of the Space-Policy Institute at George Washington University.

The announcement is obviously good news for space-transportation companies and lunar researchers lamenting the country’s 45-year absence from the moon. For those in the Mars camp, many of whom aim for a human mission to the planet by 2033, the news puts their ambitions on shakier ground.

The administration’s push for a return to the moon may be unambiguous now, but plenty of questions remain, ranging from the basic, like when and how, to the intriguing, like the role commercial spaceflight companies might play. NASA also wouldn’t be starting from scratch. The space agency has spent the last decade building the Space-Launch System and Orion, a rocket and spacecraft intended to carry people into deep space but also to build a cislunar way station called the Deep-Space Gateway. NASA planned to use the Deep-Space Gateway as a place for astronauts to prep for deep-space journeys, but the new shift could see the station being used for lunar landings.

Both time-tested contractors and growing commercial companies will be eager to work on potential lunar activities. Boeing is currently developing a capsule that would ferry people into low-Earth orbit, and SpaceX said its proposed mega-rocket, which is mostly intended to fulfill Elon Musk’s Sim City-esque ambitions for Mars, could contribute to travel to the moon. Musk, well aware of the political benefits of it, leaned heavily into lunar ambitions. “It’s 2017. We should have a lunar base by now,” he said recently. “What the hell’s going on?”

Federal support for moon research is also good news for lunar scientists like Paul Spudis, a scientist at the Lunar and Planetary Institute in Houston who writes frequently in support of a return. He dismissed NASA’s Mars ambitions as unrealistic and a public-relations stunt. “I see the vice president’s remarks not so much as a pivot in policy as a belated recognition of simple reality,” Spudis wrote in an email. “They don't have have an architecture, they don't have the spacecraft, they don't have the technology, and most assuredly, they don't have the money to bludgeon any difficulties into submission.”

Mars proponents, naturally, disagree. “We weren’t anywhere close to being ready” to going to Mars, Logsdon said, but to dismiss the objective as simply publicity is wrong. NASA has invested over the years in some research for the requirements of a mission, including life-support systems and landing technology, he said.

“Most of the people who are Mars-centered worry that we’ll get stuck on the moon, all the resources available will be focused on lunar exploration, and the idea of getting to Mars will slip indefinitely into the future,” Logsdon said.

Chris Carberry, the CEO of the nonprofit group Explore Mars, fears the same. Carberry said he’s pleased with the administration’s focus on human spaceflight and doesn’t oppose a pit stop on the moon. But he wonders whether the construction of a full-fledged lunar base could consume enough resources that would delay a Mars mission for decades. “If we got to the surface of the moon, we need to do it in a way that really is a stepping-stone to getting to Mars, not just an excuse to build a base there,” Carberry said.

In Washington, NASA’s Mars goals have received bipartisan support, which is typical for space programs in general. In March, Trump signed a NASA funding bill that included some of the strongest language about a human mission to ever appear in U.S. legislation, listing “achieving human exploration of Mars” as a key objective. The space agency has also been buoyed by interest from a general public bombarded with Hollywood movies about Mars and deep-space travel.

A renewed focus on the moon brings the United States into some alignment with space agencies in Europe, Russia, India, and China. The European Space Agency envisions building a “moon village.” Roscosmos, the Russian agency, is recruiting cosmonauts to be the first Russians to land on the moon in the 2030s. ISRO, the Indian agency, launched its first lunar orbiter in 2008 and plans to senda second mission, this time to land on the surface, next year. China has spent the last decade experimenting in cislunar space with both robotic and crewed missions, and officials have said they would put astronauts on the moon by the mid-2030s. A mission to send a rover to the far side of the moon, a first for humankind, is planned for next year. The United States is unparalleled when it comes to exploration of the solar system beyond Earth, but some in the country, particularly in the security community, worry that the country’s cislunar capabilities are rapidly atrophying.

Pence said this week he believed other spacefaring nations have outpaced the United States. “In the absence of American leadership, other nations have seized the opportunity to stake their claim in the infinite frontier,” he said. “Rather than lead in space, too often, we have chosen to drift.”

Space-policy experts say it’s too early to say who the winners and losers might be in this new chapter in the country’s space agenda. The administration has promised a robust human spaceflight program, an effort that both moon and Mars proponents can get behind. And the administration didn’t rule out a Mars mission entirely. It just chooses to go to the moon in this decade and do the other things—later.

NEXT STORY: What Are You Most Proud of This Year?