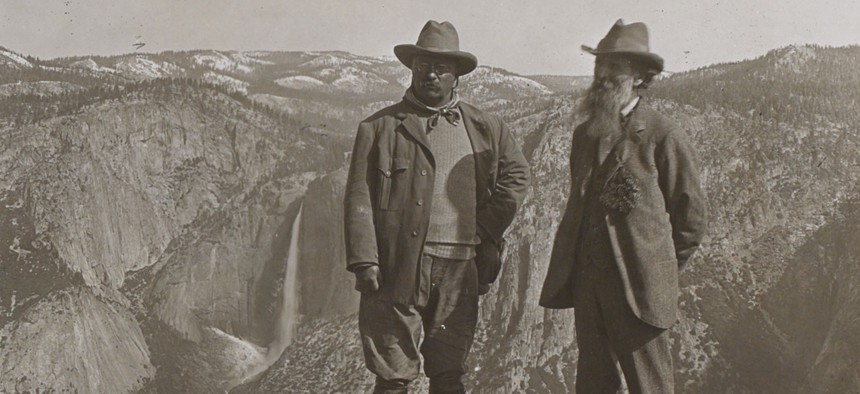

Theodore Roosevelt stands with John Muir on Glacier Point, above Yosemite Valley, California, in 1903. Library of Congress

Will Trump Change the Way Presidents Approach National Monuments?

Since Theodore Roosevelt, administrations have designated land across the country, but never before have they scaled down sites to the extent proposed by Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke.

In April, President Trump ordered Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke to review more than two dozen national monuments, arguing that the designation of sites under previous administrations had gotten out of hand. Months later, Zinke’s recommendations, detailed in a leaked memo delivered to the White House, have sparked concern among local officials and environmental groups, prompting some to describe the proposals as “unprecedented.”

Zinke recommended changes to 10 national monuments, including Utah’s Grand Staircase-Escalante and Nevada’s Gold Butte. His proposals range from lifting restrictions on activities like commercial fishing to shrinking the parameters of at least four of the sites.

The contents of the report were made publica week shy of the 111th anniversary of America’s very first national monument designation. On September 24, 1906, Theodore Roosevelt deemed an area known as Devils Tower, Wyoming, worthy of preservation under the Antiquities Act. That act, passed the same year, gives presidents the power to protect “objects of historic and scientific interest.”

Devils Tower—a tan-colored monster of a rock, looming 1,267 feet above another thousand acres of open land—was just one of the 18 national monuments Roosevelt established during his presidency. Today, the country boasts more than 150 in total, from Governors Island in New York to Death Valley in California. Only three presidents since Roosevelt—Richard Nixon, Ronald Reagan, and George H. W. Bush—opted not to designate any during their terms. Never before, though, has a president attempted to scale down monuments to the extent that Zinke proposes.

Throughout history, a few monuments have become the source of political conflict. In 1915, for example, Woodrow Wilson cut down the boundaries of Roosevelt’s designation of Mount Olympus National Monument, much to environmentalists’ dismay. This past April, Trump called former President Barack Obama’s designation of Bears Ears National Monument, an area of more than 1.3 million acres in Utah, an “egregious abuse of power.”

In his assessment, Zinke proposed shrinking Bears Ears from 1.35 million acres to roughly 160,000, saying changes would “provide a much-needed change for the local communities who border and rely on these lands.” Still, environmental groups have pledged to fight Trump in court if he follows through on the recommendations.

I spoke with Mark Squillace, a law professor at the University of Colorado Boulder and former assistant to Bruce Babbitt, the interior secretary under President Bill Clinton, about the unprecedented territory the Trump administration has entered into—and the history behind a significant presidential power. Our conversation has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Lena Felton: Let’s start at the very beginning and go back to the Antiquities Act of 1906. What was the significance of Congress granting the president sole power to protect sites?

Mark Squillace: I think it’s fair to say that people weren’t exactly sure about the breadth of the Antiquities Act when it was passed, but there clearly was a desire on the part of some of the people that were pushing this legislation to have more expansive authority than the narrow protection of small sites around our archeological digs. There clearly was some interest in kind of a broader type of legislation.

A large part of the reason for the Antiquities Act was to allow the president to act quickly to protect land. We can get into this later, but the big debate right now is whether it’s a one-way protection or whether the president somehow has the authority to undo protections made by previous presidents. If you think about the fundamental reason for the law in allowing quick protection before somebody can come in and undermine those protections by building roads, by locating mining claims, by logging timber, whatever they might want to do—you need to act quickly, and you need to do it in a way that’s protective.

Felton: Can you talk a bit about Theodore Roosevelt’s role in being the first president to use that power?

Squillace: The designation and decision that Roosevelt makes in 1908 to proclaim the Grand Canyon National Monument was one of the things that really changed the history of the Antiquities Act going forward. The Grand Canyon National Monument in 1908 was over 800,000 acres when it was designated, and it fairly soon thereafter led to a lawsuit by a guy by the name of Ralph Henry Cameron, who had located some mining claims around the Grand Canyon.

This, the famous case under the Antiquities Act, is called Cameron vs. United States, in which Cameron basically makes this argument that the Antiquities Act was a law designed to protect these small ancient sites with archeological finds, that it was not meant to protect these large landscapes, if you will. And the Supreme Court, in a rather short opinion … simply says that the Grand Canyon is one of the greatest eroded canyons in the United States, if not the world. It essentially says that clearly it’s an “object of scientific interest,” and says the Court has no problem confirming the designation of the Grand Canyon under the Antiquities Act. It seems to me that the Cameron case is going to be extremely important going forward, particularly if the Trump administration decides to pull back on some of the monuments that were previously declared.

Felton: Besides Roosevelt, did any other presidents use their power to designate national monuments in far-reaching ways?

Squillace: It’s remarkable, a number of Republican presidents [have]. It has been a bipartisan thing to designate national monuments. Herbert Hoover designated a bunch, Calvin Coolidge designated a bunch. Franklin Roosevelt, of course, designated quite a few. Particularly in the first half of the 20th century, there was really a lot of movement to try to protect lands that were deemed to be worthy of conservation.

We also end up getting this large number of some fairly substantial and impressive monuments towards the end of the Clinton administration. I don’t have the number off the top of my head, but it was something over 20 monuments that ultimately are designated or expanded by President Clinton. Until Barack Obama, at least, it was clearly the most aggressive and ambitious expansion of our national-monument system. … And, you know, George W. Bush, largely at the behest of his wife—Laura Bush was particularly a fan of the marine monuments, and persuaded her husband, I think, to push for the designation of a couple of large marine monuments off the coast of Hawaii. Obama took a cue from that work, and also designated a couple of big marine monuments that seem to be at least somewhat at risk from the recommendations that are coming [from] Secretary Zinke right now.

Felton: There were three presidents—Nixon, Reagan, and George H.W. Bush—who chose not to designate national monuments. Why might a president opt out?

Squillace: Well I think that presidents have different sorts of connections and attachments to the land. Richard Nixon never designated a monument—he was not really known as an outdoorsman in the way that some others are. As I said, many conservative presidents had no problem going forward and designating national monuments. I think it partly just depended on their relationship to the land, their interest in outdoors activities, and perhaps the people they surrounded themselves with—the secretaries of the interior, and the other people that were advising them about particular monuments.

Felton: That’s a good segue to the present. What do we know about this president’s—and Interior Secretary Zinke’s—approach to national monuments?

Squillace: Here we are today, Barack Obama having designated quite a few important national monuments, many large—of course the one that seems to get most of the attention is Bears Ears, but there are quite a few other significant monuments. And now we have a new secretary of the interior and a new president who seem interested in trying to pull back on some of these. For lawyers and academics like myself, the interesting question that we’re all trying to deal with is whether or not the president actually has the authority to do this.

[Zinke] seems to be taking this position that it’s wrong for the president to close off lands to what I think he describes as “traditional uses” of the land—that this should be exercised and the law should be construed very narrowly so the president doesn’t have this broad power to set aside these large landscapes. I think economics is part of the argument. But the economics argument is particularly odd, I think, because all the evidence we have suggests that national monuments stimulate local economies, they don’t harm local economies.

So the question is: What’s going on here with Zinke and his push to undermine some of these monuments? Is it a good thing or a bad thing that Zinke’s trying to do this? What I would say is, if we allow any future president to come in and second guess the choices that were made by prior presidents, the Antiquities Act is going to become this sort of whipping boy for every president that comes in. You can almost imagine if Trump decides to shrink Bears Ears and is able to get away with it, for example, the next president comes in and decides to reverse that decision and redesignate the land as a national monument—and it just sort of bounces back and forth, depending on the presidents and their predilection and whether they support the protection of public lands or mineral development or some other kind of use of the land. I just don’t think the law can work if it becomes this punching bag among presidents going forward.