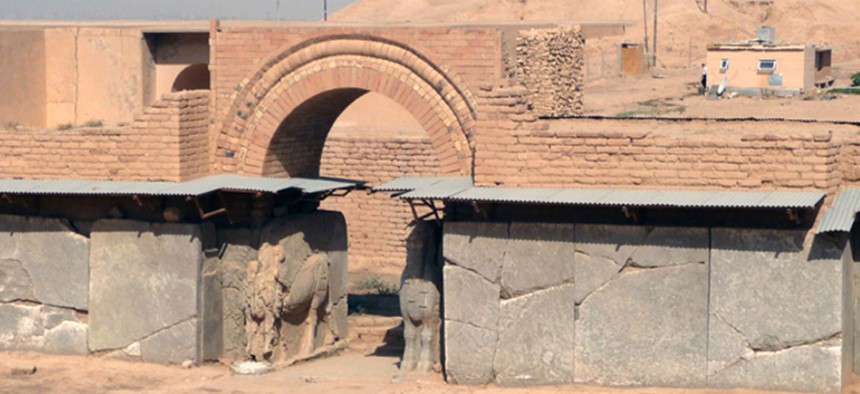

Nimrud, Northwest Palace Photo by Col. Mary Prophit/U.S. Army Reserve

State Department Teams With Smithsonian to Rescue ISIS-Harmed Antiquities

The $400,000 project with the Smithsonian Institution preserves artifacts at Nimrud, a site familiar to readers of the Bible.

The progress Iraqi and U.S. forces have made in combating ISIS is uneven but tangible.

And one of the benefits to newly liberated territory in the Near East is renewed access to the antiquities sites the Islamic extremists had pillaged.

On March 31, the State Department announced a new $400,000 project managed jointly with the Smithsonian Institution to provide emergency protection and preservation of artifacts at one site familiar to readers of the Bible.

Nimrud, on the Tigris River in northern Iraq, about 30 kilometers southeast of Mosul, dates to the sixth millennium B.C. and later became the capital of the neo-Assyrian empire.

ISIS combatants invaded the area in June 2014, and reports of damage to the antiquities came as early as January 2015, according to a May 2015 report from the American Schools of Oriental Research based on 30 months preparation. The risks include theft, vandalism and exposure to the elements.

“What ISIS has sought to destroy, we are determined to set right,” said Assistant Secretary for Educational and Cultural Affairs Mark Taplin. “It is in America’s interest to contribute to a better future for Iraq. Time and time again, we have seen how collaboration in cultural heritage protection and preservation fosters dialogue and understanding within societies under stress.”

In interviews with Government Executive, State Department and Smithsonian staff working on the project discussed their travels to the region to help locals assess damage, provide security and safety equipment, shelter damaged objects and stabilize stone reliefs.

The previous documentation of the damage was obtained through satellite imagery and contacts, noted Andrew Cohen, the State Department’s senior cultural property analyst. “Now, as new territory is retaken, it’s an opportunity to put some reality into that picture.”

All the U.S. agency work is done under supervision of the Iraq government’s antiquities and heritage agency, he said. The State-Smithsonian partnership goes back to 2009, when the U.S. embassy established the Iraq Institute for the Preservation of Culture and Heritage. The American government employees work out of the Iraqi city of Erbil, which has been safe from ISIS attacks, while the onsite work at Nimrud is performed by Iraqis, Cohen said.

The project chose Nimrud “not just because the site is available, but because it was the first capital of an empire that stretched from Iran to the Mediterranean and Egypt and figures prominently in the Bible,” Cohen said. The 900-acre area, now a protected archaeological preserve, once contained a citadel with 40-foot walls and four imperial palaces.

The alabaster reliefs on walls and glazed tiles portray significant historical events. The Iraqis had listed them as part of their cultural heritage following excavations in the 19th century, Cohen explained. “That’s why ISIS tried to destroy the most picaresque part in a dramatic way that was recorded, filmed and photographed—one of their signature events.”

One of the U.S. goals is to equip Iraqis to take on new preservation challenges as other territory is reclaimed to free up classic antiquities in Mosul, Palmyra and Nineveh, he said, many of them “of significance to Jews and Christians.”

The Smithsonian contributors all have years of experience working with the State Department in Iraq, said Jessie Johnson, a conversation specialist who worked on post-war repairs to the National Museum of Iraq in Baghdad. The new project is “a continuation of a very amicable relationship.” She trains locals in how artifacts deteriorate and how they can be reassembled, as well as training employees of the Homeland Security Department in countering international trafficking of antiquities.

The Iraqis are impressive in their commitment, Johnson said, noting that many venture to unsafe parts of the country to “work together on something they love and that is important to them and their communities.”

The Smithsonian staff do not personally travel to dangerous sites, though “we are concerned for our colleagues,” said Cori Wegener, an art historian who specializes in how museums handle disasters. Her team doesn’t worry about enemy troops returning because they maintain good communication with the State and Defense departments. “But there are safety issues about whether people should be walking around on the site because of dangerous unexploded ordnance,” she added.

The Iraqis are not the only beneficiaries of the project, said Katharyn Henson, an archaeologist now working to remap the Nimrud site to improve the accuracy of damage descriptions based on satellite imagery. “The things we’re talking about you would classify as universal human history. They’re not specific to one part of the world, but part of our collective heritage.”