M DOGAN/Shutterstock.com

Treasury Announces $1 Billion in Hardest-Hit Fund for the Fight Against Blight

The money will go toward preventing foreclosure and stabilizing troubled housing markets in the states hit hardest by the housing crisis and recession.

The big news from the U.S. Department of the Treasury Wednesday is that Harriet Tubman will replace former U.S. President Andrew Jackson on the front of the $20 dollar bill. She’d been floated previously as a candidate for the new face of the $10 bill. Buoyed by a certain Pulitzer Prize–winning musical, however, Alexander Hamilton is not throwing away his spot on the ten. Other figures from the women’s suffrage and Civil Rights movements are expected to join them on the faces of U.S. money.

Treasury announced some other important news Wednesday, too. The department isdedicating $1 billion to fighting blight. That’s 50 million $20 bills that will go toward preventing foreclosure and stabilizing troubled housing markets in the states hit hardest by the housing crisis and recession.

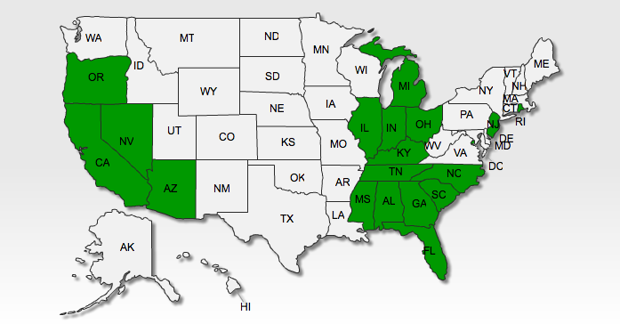

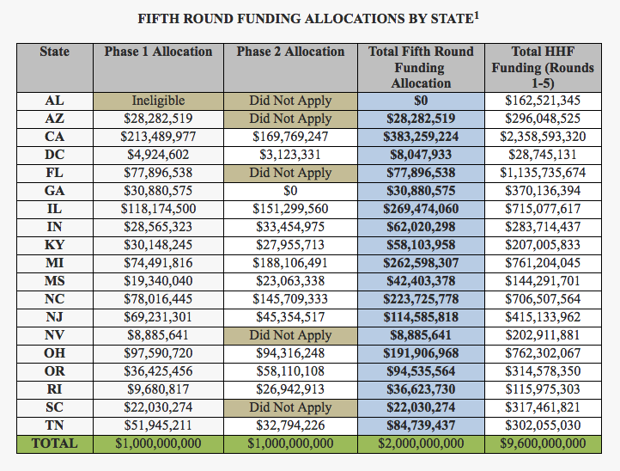

This $1 billion allocation is the fifth and final round of disbursements under the Hardest Hit Fund, a program launched in 2010 under the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) to help anchor distressed neighborhoods in 18 states and the District of Columbia. All told, Treasury has given $9.6 billion—480 million Tubmans—to troubled markets through the Hardest Hit Fund.

Distribution of the Hardest Hit Funds by state. (Dept. of Treasury)

Typically, these funds have helped homeowners who are unemployed or underwater on their mortgages. (Keeping homeowners in their homes is one clear way to prevent blight.) But the Hardest Hit Fund has worked to keep homes from going dark in other, more novel ways. Each state and D.C., through its state Housing Finance Agency, both administers and designs the Hardest Hit Fund programs. That gives states a lot of leeway in deciding how best to fight vacancy.

Treasury has also proven spry in its administration of the overall program. When Congress first approved the Hardest Hit Fund as part of the same package that bailed out the banks and auto industry, the idea was to throw a life preserver to homeowners at risk of foreclosure. But as Alan Mallach, senior fellow for the Center for Community Progress, noted back in 2014, several of the hardest-hit states—namely Michigan and Ohio—were facing a different problem by late 2011. Plenty of homeowners had already abandoned their homes.

“Thousands of houses were being abandoned in those states’ cities, pushing down the value of neighboring properties, destabilizing neighborhoods, and indirectly exacerbating the very problem that HHF was trying to deal with: houses going into foreclosure and families losing their homes,” Mallach wrote.

In spring 2013, after months of discussion between state and federal officials, the Michigan State Housing Development Authority asked Treasury for formal permission to use some of its Hardest Hit Fund money to demolish vacant properties—an immediate salve for blight. Treasury found the legal authority under the TARP legislation to say yes.

The mechanics of how this creative TARP reading works get kinky at the level of the state’s disbursement to counties and cities. But as of the end of 2015, the Hardest Hit Fund had nevertheless paid for some 9,000 property demolitions in Michigan, Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, and other participating jurisdictions. That’s a big federal push for eliminating blight, for a program that was never designed by Congress as such.

Today’s fifth and final round was obligated by Treasury back in February, and states have through December 31, 2020, to spend the money. Here’s abreakdown of where the money is going and how each state is spending the money as well as some stories from homeowners whose lives were changed by the program.

The money matters to places suffering under the weight of blight. Michigan—whose Hardest Hit Fund money has alleviated blight in the hardest-hit cities of Detroit, Flint, Pontiac, Grand Rapids, and Saginaw—has already announced that it will put its $188 million allowance toward removing blight.

“Coupled with the funding allocations announced back in February, the impact on blight removal will likely be even greater,” Mallach tells CityLab in an email. “While many other pieces need to go into a comprehensive blight-elimination strategy, demolition is a critical part of the picture, and a critical step in beginning to rebuild distressed urban neighborhoods.”

NEXT STORY: Stop Complaining About Your Indecisive Boss