The sun shines on Pershing Park in 2006. Elvert Xavier Barnes Photography via Flickr

How Many National World War I Memorials Does D.C. Need?

Preservationists think D.C.'s first national World War I memorial should be restored before another is added.

Late last year, Congress authorized a new National World War I Memorial for Washington, D.C. Just last month, that memorial took its first step toward becoming a reality. But there’s a hitch: The site that legislators picked out for the monument is already home to a World War I memorial. Predictably, the plan has sparked a skirmish over the best way to remember the War to End All Wars.

Pershing Park opened in 1981 just a block from the White House. The park honors U.S. Army General John Joseph “Black Jack” Pershing, who led U.S. forces to victory during the Great War. Pershing was a big deal. He’s the only commander ever to achieve the title of “General of the Armies” during his lifetime. The only other leader who got that grade (posthumously) was George Washington.

Pershing Park is where the U.S. World War I Centennial Commission intends to erect its new monument—even though the park already stands as a memorial to one of the war’s greatest heroes. Late in July, the Commission debuted some 350 entries it received in an open design competition for the National World War I Memorial. But the plan has rankled at least one landscape advocate, who says that Pershing Park, like its namesake, is also a big deal.

“There’s a lot of opportunity at Pershing Park without destroying the key and signature elements of what’s there today,” says Charles Birnbaum, president of the Cultural Landscape Foundation.

That’s why the Cultural Landscape Foundation is announcing this morning a campaign to urge National Mall and National Park Service stakeholders to preserve Pershing Park. The group is asking leaders to add it to the Pennsylvania Avenue National Historic Site—a move that would slow any radical changes to it, including a new memorial. (Parts of Pennsylvania Avenue were granted National Register of Historic Places status in 2007, but not the park, which was only 20 years old at the time when the nomination effort was begun.)

Pershing Park as pictured in 2010. (Tim Evanson/Flickr)

Pershing Park merits another look. It was designed by M. Paul Friedberg, one of the greatest modern landscape architects. Friedberg received the American Society of Landscape Architects Design Medal in 2004 and the ASLA Medal in 2015, the two highest honors in the field. The D.C. park is also the product of the firm Oehme, van Sweden & Associates. In October, the National Building Museum will open a retrospective on Wolfgang Oehme and James van Sweden, whose work “revolutionized modern American landscape architecture.”

The park plaza design, Friedberg’s signature element, descends into a sunken basin surrounded by granite terracing. The “softscape” by Oehme and van Sweden was an early example of the firm’s New American Garden aesthetic, which favored native and seasonal plantings. (Where would New York’s beloved High Line be today without those wild grasses?) A hollow, rectilinear fountain at Pershing Park houses a zamboni; the water feature doubled as an ice-skating rink during winter—back when it worked.

Pershing Park occupies pride of place in the capital: It’s a stone’s throw from the White House, the U.S. Treasury Building, and the Willard Hotel (where Julia Ward How wrote “The Battle Hymn of the Republic”). But you wouldn’t know it from visiting it today. The Washington City Paper called it a “ghostly place” in a 2012 article detailing all the failings of the federal contractor that has overseen it for decades. Now, the fountain is broken; delightful chairs and tables that once graced the park have been replaced by concrete benches; and the plantings and sunken water garden are long gone.

“When you have a landscape that has a water feature, and you stop maintaining the water feature, then you stop maintaining the plantings at the same level,” Birnbaum says. “What we have here is bare-minimum maintenance. They empty the garbage. ”

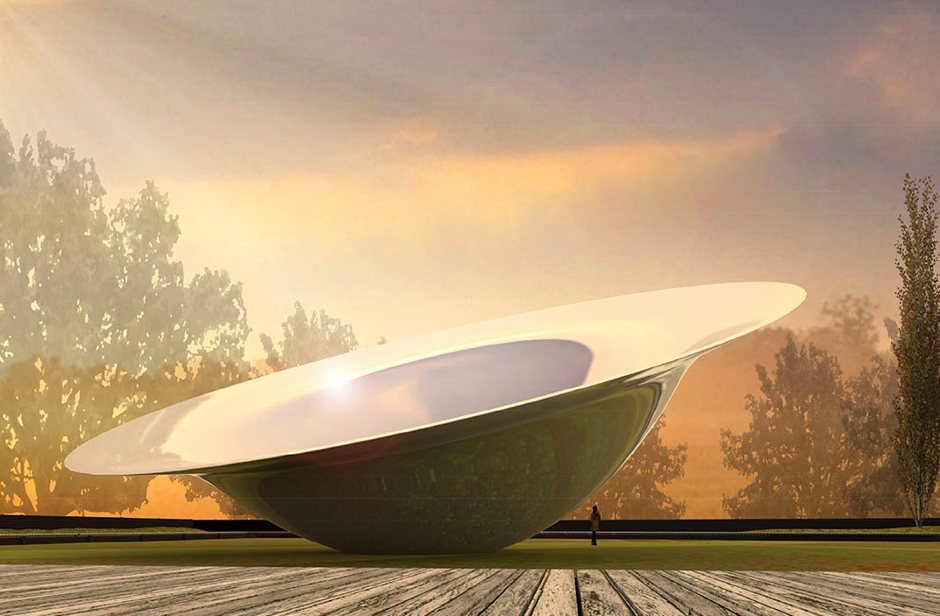

Perhaps that’s why so many of the designs for the (new) National World War I Memorial call for completely demolishing and replacing Pershing Park. At a glance, a huge majority of the more than 350 designs treat Pershing Park as if it were a vacant lot. Many feature classical or figurative elements that would be out of step with the existing modernist landscape architecture.

Design entry #10, “The Honor,” one of more than 350 competition submissions. A little on the nose, no? (WWI Centennial Commission)

Several of the best modernist landscape projects in America are endangered. Preservationists fought hard for Peavey Plaza, Friedberg’s greatest work, in downtown Minneapolis. They succeeded in placing it on the National Register of Historic Places, forcing the city to abandon plans to demolish it. Plans to restore it are finally underway. And in Fort Worth, Texas, there’s a renewed effort to restore Heritage Park and Heritage Plaza, designed by Lawrence Halprin, a landscape luminary—thanks in part to Laurie Olin, maybe the greatest practitioner working today.

“Just like Peavey [Plaza], people forget what [Pershing Park] looked like, and they are very quick to see it go away,” Birnbaum says. “Any work of landscape architecture has the ability to adapt and evolve. I think there’s a real difference between wholesale demolition and removal and thinking about how you adapt a place to serve multiple audiences.”

For his part, Birnbaum doesn’t rule out the possibility of adapting Pershing Park as a National World War I Memorial. (Although he does offer that a skating rink is probably incompatible with a monument to fallen soldiers.) The park as it stands now—or as it once stood, anyway—might be better in keeping with the mission of a memorial than many of the competition entries. Consider the atmospheric National September 11 Memorial, featuring fountains, landscaping, and a plaza, designed by Michael Arad and Peter Walker.

“Whatever you think about the World War II Memorial,” Birnbaum says, “when you go there on a hot day and see all of those people in that basin, it’s incredible.” (The National World War II Memorial is nobody’s favorite design.)

Restoring Pershing Park ought to be a no-brainer. It would certainly suit the adjacent hotels to reverse years of deferred maintenance and reclaim what was once a well-loved D.C. park. Today, it’s a sorry site, but not an unfamiliar one. The park falls under the jurisdiction of the National Park Service (even though it belongs to the city), which “has long struggled with underfunding,” according to the National Parks Conservation Association.

For now, the Cultural Landscape Foundation hopes to forestall any decision that will undermine the integrity of Pershing Park. “The competition language discusses any proposed design interventions in terms that seem benign,” says the group's statement, “but the proposed $20-25 million budget points to wholesale changes.”

Whatever shape they take, those changes aren’t in the offing anytime soon. The National Park Service, the National Capital Planning Commission, and the U.S. Commission of Fine Arts, at a minimum, will need to sign off on any design selected by a jury. Presuming that Congress won’t appropriate the funds for aNational World War I Memorial, its backers will need to raise the money.

So any final decision will be a long ways off. All the better reason to restore Pershing Park as the nation’s World War I memorial now. As Roll Call noted back in January, “Achieving approval to establish a National World War I Memorial in the District of Columbia took longer than the war itself.”

(Image via Flickr user Elvert Xavier Barnes Photography)