Hurricane Katrina destroyed neighborhoods in 2005. Jocelyn Augustino/FEMA

Housing Choices for Poor Families Have Not Improved Since Katrina

A new study shows that vouchers for low-income families in post-Katrina New Orleans haven’t helped integrate or improve neighborhoods.

Approximately 70 percent of homes in New Orleans were damaged in the floodwaters of Hurricane Katrina, including half of the city’s rental housing stock. Much of that pre-Katrina landscape belonged to low-income residents who had little opportunity to live in neighborhoods that weren’t saturated with poverty. The few neighborhoods characterized by families living above poverty actively worked to keep low-income families away. Ten years after Katrina, not much has changed.

A new report from Tulane University researchers Stacy Seicshnaydre and Ryan C. Albright reveals that the bulk of low-income families in New Orleans continue to live in neighborhoods mired in poverty and racial segregation, despite the new housing stock that has emerged in the post-Katrina recovery. Before the storm, the main living option for low-wage earners was public housing, in projects that hosted nearly 5,000 units across the city. Almost all of those have been demolished (per pre-Katrina U.S. Housing and Urban Development dictum), and replaced with mixed-income developments.

Today, federally issued housing vouchers are the primary tool that low-wage residents use to pay for homes. In theory, vouchers can be used to move into any unit on the private market. However, Seicshnaydre’s and Albright’s analysis of voucher use shows that they have not afforded poor New Orleanians better housing choices. A key section of their report reads:

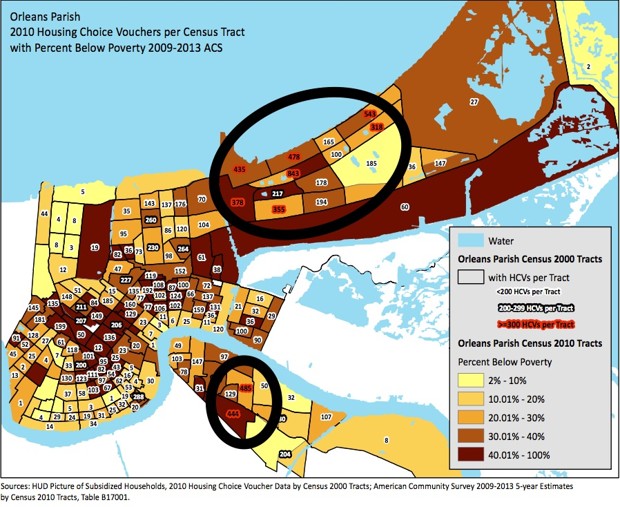

An examination of voucher households reported by HUD in 2010 reveals that 25 percent of the vouchers were used in 5 percent of the census tracts (4,279 total vouchers used in nine tracts). In each of these nine tracts, more than 300 vouchers were used, which is triple the amount that would be present if vouchers were evenly distributed across all tracts. The number of vouchers appearing in these tracts ranged from 318 to 843. Seven of the nine census tracts are located in New Orleans East; six of the nine tracts in this group are in high-poverty areas

The map below shows that the nine high-poverty/high-voucher household census tracts are in just two areas of the city. The first circle at the top of the map is New Orleans East.

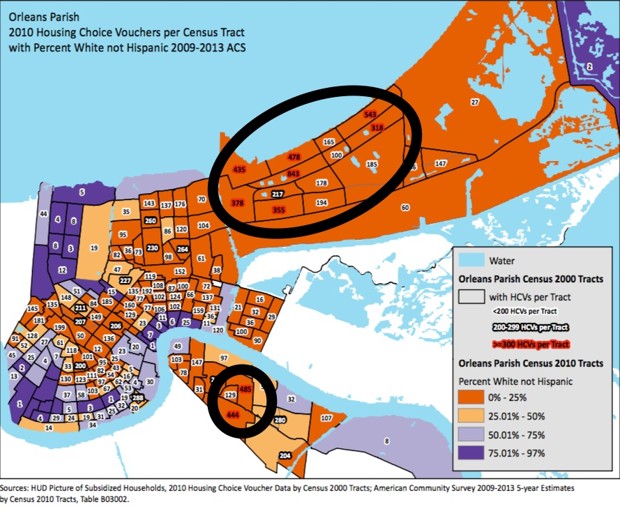

New Orleans is a predominantly African-American city, so it’s tempting to chalk up such disparities to a class prejudices. However, many of those living in New Orleans East are working- and middle-class families. Meanwhile, all of the nine tracts with the largest volume of voucher families are areas where whitehouseholds make up less than 25 percent of the population. The purple census tracts on the map below show that areas where households are more than 75 percent white host the fewest numbers of families using vouchers.

Considering that 90 percent of New Orleans’ voucher holders were African Americans in 2010, there is pretty good evidence that racial discrimination vouches for much of these disparities. This much was verified in a 2009 auditconducted by the Greater New Orleans Fair Housing Center, which found that landlords refused to take voucher tenants in 82 percent of their test cases. (Full disclosure: My wife, Thena Robinson, formerly worked at the Fair Housing Center and helped conduct some of these audits.)

A separate audit, conducted by the fair housing center in 2014, found that 44 percent of African-American testers were treated unfavorably compared with white testers when they sought housing in non-impoverished communities. Here, “unfavorable” meant that landlords were unresponsive, refused to show apartments, or imposed stricter standards on potential black tenants.

“Both race-based rental audits and voucher-based audits conducted post-Katrina in the region reflect market barriers that limit housing choice for those attempting to use vouchers to gain wider housing mobility and opportunity,” reads the report.

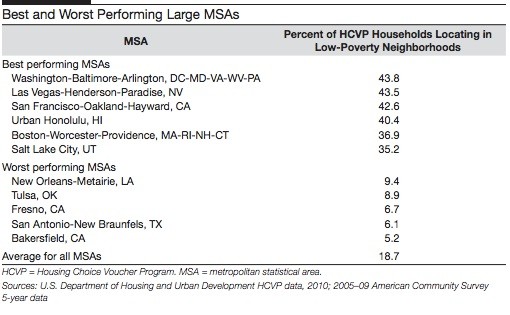

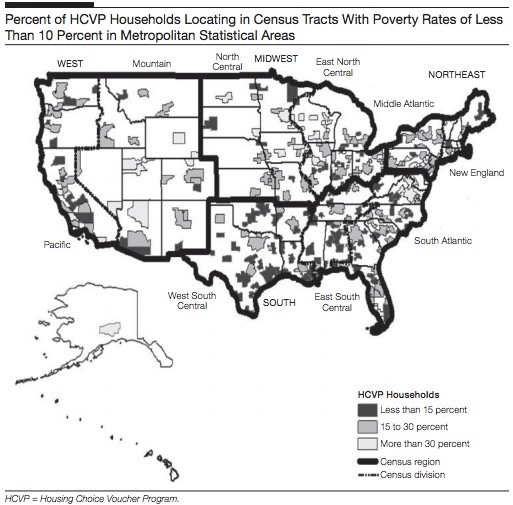

It’s no surprise then that New Orleans has been one of the worst cities for low-income people seeking better quality neighborhoods to live in, as seen in the chart below. This is compounded by a recent report citing New Orleans as having the second-worst income inequality of all major cities across the nation.

Despite this poor showing for voucher families, the report’s authors say that the New Orleans metro area has been slowly trending away from concentrated poverty—while the national trend is moving in the opposite direction. A recent U.S. Supreme Court ruling affirming that more low-income housing should be developed in wealthier neighborhoods could change that, though.

For New Orleans to continue on a course toward fairer housing options, the researchers recommend more rigorous protections from discrimination. Their report also calls for setting voucher values based on average rents across neighborhoods rather than across metropolitan areas, as CityLab reported on recently. Concludes the report:

The stakes are high for the low-income children in our region. The housing voucher program must be used to its fullest potential—assisting the next generation of New Orleans children to overcome the life-altering effects of poverty.