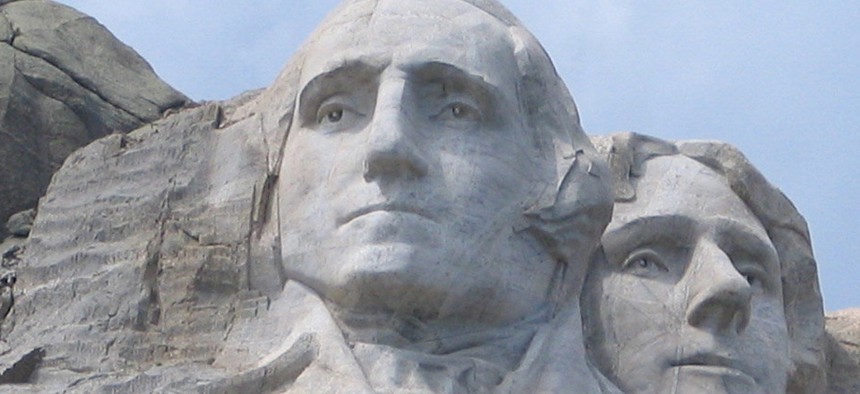

Barbara A. Harvey/Shutterstock.com

Americans Didn't Always Worship the Founding Fathers

After the Civil War, the men who framed the Constitution gradually rose to become the Ghosts of Democracy Past: courageous, learned, and super-judgey.

A dozen years after H.W. Brands argued in The Atlantic that we pay too much deference to the Founding Fathers , “What would the Founders think?” is still a go-to invocation. In our collective imagination, the Founders tend to be reincarnated in modern-day America, capable of only one thought: “SMH.”

Here, for example, is a recent NASCAR ad by Parks and Rec's Nick Offerman suggesting that our bewigged forebears would look unkindly upon SMS and/or emoji (and possibly gluten-free diets):

This is also more-or-less the premise of a 2013 novel called The New Founders . And it’s a ubiquitous trope in opinion writing: Here’s Michael Shermer in TIME suggesting that the Founders would have frowned on the anti-vaccination movement .

In his September 2003 Atlantic story, Brands himself supposed that the Founders would have been dismayed by what they found in today’s U.S.

But what would have dismayed the Founders most, Brands said, is this very tendency to invoke them as referees in today’s debates:

In revering the Founders we undervalue ourselves and sabotage our own efforts to make improvements—necessary improvements—in the republican experiment they began. Our love for the Founders leads us to abandon, and even to betray, the very principles they fought for. … We agonize over ‘original intent’ as if what the Founders believed ought to determine the way we live two centuries later. They would have laughed, and then wept, at our timidity.

Brands made a compelling case that our reverence for the Founders is relatively novel. During the first 50 years of independence, as the electorate expanded, he said, it was the people—the soldiers of the revolution—who drew the most praise: “The common man came to the fore, and the old elites—including, after the fact, the Founders—lost ground commensurately.”

And then there was the matter of slavery:

Americans of the second quarter of the nineteenth century were compelled to confront the deficiencies of the Founding. The landmark documents of the Revolutionary era—the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution—were scrutinized and found wanting. The abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison was so outraged at the Constitution and its framers for fastening slavery upon the American body politic that he damned the federal charter as ‘a covenant with death and an agreement with Hell,’ and publicly burned his copy.

In Brands’s telling, the end of the Civil War brought about the first great uplift in the Founders’ reputation. Twentieth-century jingoism, fueled by war, made criticism of the Founders impolite. And somehow, over time, they’ve become the Ghosts of Democracy Past: courageous, learned, and super-judgey.

If they were resurrected in today’s America, the Founding Fathers would find themselves awash in founders, most notably the never-ending stream of gurus from Silicon Valley encouraging us to fail fast and embrace the maker within . But our reincarnated Founders might find a more fascinating set of peers outside America. Around the world, revolutions are giving way to constitutions and governments, and the makers of these institutions find themselves wrestling with many of the same challenges our Founders faced. What should be the role of religion in our society? What exactly do we mean by “equality,” and who gets to have it?

Of course, they’d also find many new realities. This January, Tunisia celebrated the first anniversary of a brand-new constitution. Among the many groups involved in the construction of the document was a small NGO called al-Bawsala (“the Compass”). As the fledgling democracy took shape, the workers of al-Bawsala documented parliamentary sessions— on Twitter , on the Web —opening up the machinery of politics for everyone to see. Le Monde dubbed the group “the Incorruptibles.” According to al-Araby al-Jadeed, Tunisian MPs eventually took to texting excuses to al-Bawsala’s civilian observers —“I am ill,” “Family emergency”—when they had to miss a vote. Apparently, contra Nick Offerman, these founders actually valued SMS rather than disdaining it.

The American Founders, Brands wrote, “were no smarter than the best their country can offer now; they weren't wiser or more altruistic. They may have been more learned in a classical sense, but they knew much less about the natural world, including the natural basis of human behavior. They were, however, far bolder than we are. When they signed the Declaration of Independence, they put their necks in a noose; when they wrote the Constitution, they embarked on an audacious and unprecedented challenge to custom and authority.”

We see that same boldness in contemporary founders, with a few more lessons besides: that the promise revolutions hold is always freighted with peril, and that fragile democracy, hard-won, requires constant vigilance.

( Image via Barbara A. Harvey / Shutterstock.com )