"Do these glasses contain gin?" Sebastian Duda/Shutterstock.com

Getting Animals Drunk for Science

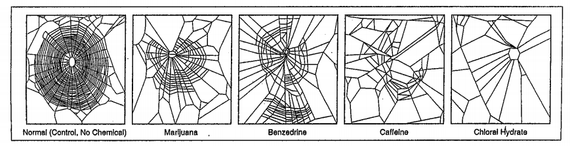

NASA and NIH show that tipsy zebra finches slur their songs and high spiders spin asymmetrical webs.

Feed a songbird enough spiked punch and it will begin to slur its song. We know this because scientists recently got some zebra finches drunk .

The zebra finch was of particular interest to researchers because the species learns song "in a manner analogous to how humans learn speech," according to an abstract for a study published this month in the journal PLOS One.

Humans have a long history of tinkering with animals' sobriety this way. The first pap smears, for example, were done on drunk guinea pigs . Drunk honeybees, scientists have found , will spend less time grooming themselves and more time upside down. And NASA famously studied the web patterns of spiders on a variety of drugs.

NASA

Because of ethical concerns over using humans in drug and and alcohol experimentation, a "substantial portion" of the research on intoxication and alcohol dependence is done on animal subjects, according to the National Institutes of Health . (Rats and mice are the most commonly used subjects for such testing at the NIH.)

Of course, there are plenty of potentially intoxicated creatures to observe in the wild, too. Scientists have long puzzled over the question of whether animals seek out mind altering substances because they want to get intoxicated. Reindeer forage for hallucinogenic mushrooms. Elephants guzzle fermented fruit juice. Wallabies eat opium poppies . Swedish elk are known to tip back the fermented apples each autumn. Some monkeys —especially the juveniles—will pick alcoholic drinks over sugar water. And bears have, on occasion, been known to binge drink. ( This one drank 36 cans of beer from a campsite.)

So we know that animals are attracted to alcohol but it's less certain whether they actually get drunk. (One species of bat, researchers have found , will opt for the sugar that sobers them up.) "I get a lot of anecdotes about drunken animals," evolutionary physiologist Robert Dudley said in an interview with the University of California at Berkeley about his research. "But it is so hard to know whether it’s natural, or whether they are drunk..." Dudley says animals may not drink to get drunk, but instead for survival—which could help explain why humans flock to the stuff, too. "It was kind of a fun realization that there is an ancestral, almost neurological bias associating ethanol with nutritional reward and caloric gain."

(Image via Sebastian Duda / Shutterstock.com )