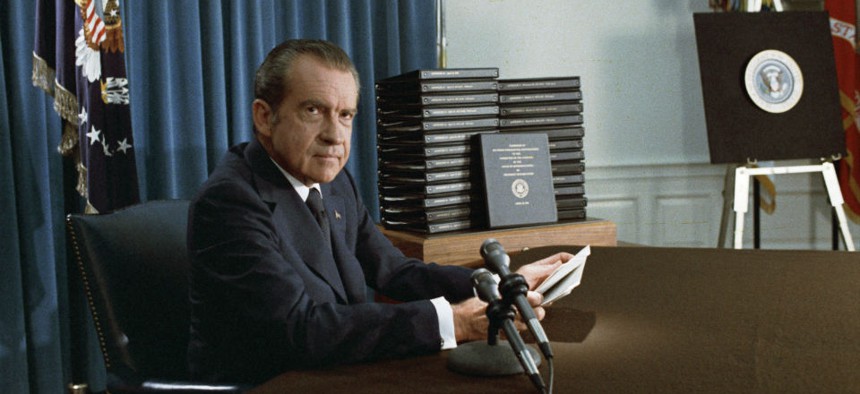

President Nixon, with edited transcripts of Nixon White House Tape conversations during broadcast of his address to the Nation in 1974. Wikimedia Commons

The Things You Don't Know About the Nixon Tapes

Forty years after Watergate, two new books show how little we knew about the disgraced president.

Richard Nixon taped roughly 3,700 hours of his conversations as president. About 3,000 hours of those tapes have been released, while the rest remain closed to protect family privacy or national security. The public has a general impression of what’s on the Nixon White House tapes—the expletives deleted, the so-called “smoking gun” when Nixon appeared to try to use the CIA to derail the FBI investigation of Watergate, the slurs against blacks and Jews.

But very few people have actually listened to more than a few hours of tapes. Less than five percent of the recordings have been transcribed or published. The tapes, stored at the Nixon Library in Yorba Linda, California, will in time give us a much clearer and more accurate picture of Richard Nixon. Two tapes-based books published this summer, timed to the 40th anniversary of Nixon’s resignation on August 9, 1974, go a long way toward showing Nixon’s underappreciated geopolitical genius and how he became the victim of his own emotionalism.

The Nixon who emerges from Luke Nichter and Doug Brinkley’s massive (700-plus pages) The Nixon Tapes, a collection of transcripts from 1971 to 1973, is at times profane and raw. Speaking of Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, he tells National Security Adviser Henry Kissinger, “We really slobbered over that old witch.” He shows the typical prejudices of his generation against gays. But there is no doubt that he is in charge—ruthlessly so, exploiting rivalries between his aides. He seems to delight in secrecy and in playing the great game of power diplomacy, even when he is frustrated by the Russians, Chinese, and North Vietnamese, as well as America’s allies. It’s not always clear where Nixon is going—he vents, rages, tries on bluffs and provocations—but he, and not Kissinger, is calling the shots.

He also emerges as daring and cunning. In 1972, Nixon runs the risk that the Soviets will cancel a crucial summit meeting in the spring if he bombs Hanoi and mines Haiphong harbor as part of his relentless (and vexed) effort to pressure the North Vietnamese. The bet paid off. The Soviets looked the other way—they wanted arms control—and Hanoi finally got the message and agreed to a peace deal.

But Nixon’s emotional neediness shows through, and not just once or twice. He is obsessed with John F. Kennedy, or more specifically, Kennedy’s image in history, which Nixon feels (not without justification) was inflated. On April 15, 1971, Nixon complains to Kissinger and his chief of staff, H.R. “Bob” Haldeman, “Kennedy was cold, impersonal, he treated his staff like dogs.” (Nixon was more considerate to his staff.) “His staff created the impression of warm, sweet and nice to people, reads lot of books, a philosopher, and all that sort of thing. That was pure creation of mythology .…”

As he often did, Nixon then complains he’s not getting credit for his virtues and blames his staff. “For Christ’s sake, can’t we get across the courage more? Courage, boldness, guts? Goddamn it! That is the thing!” He rants on, fishing for reassurance:

NIXON: What is the most important single factor that should come across out of the first two years? Guts! Absolutely. Guts! Don’t you agree, Henry?

KISSINGER: Totally.

Nixon tried to control his feelings, pretending he did not resent the press, but from time to time his anger surged up, occasionally in rash ways. Remarkably, we still do not know who ordered the June 1972 Watergate break-in that led to Nixon’s downfall. There are lots of theories, including CIA plots and convoluted conspiracies about sex rings, but no conclusive evidence. There is, however, recorded proof of Nixon ordering a different break-in—at the Brookings Institution in 1971. This is the starting point for Ken Hughes’s intriguing new book, Chasing Shadows: The Nixon Tapes, the Chennault Affair, and the Origins of Watergate.

When the New York Times began printing the Pentagon Papers in June 1971, Nixon and his aides were outraged at the leak of secrets—but they also saw a chance to pile on the Kennedy and Johnson administrations. On the eve of the 1968 election, President Johnson had halted the bombing of North Vietnam—in an attempt, Nixon suspected, to help his Democratic opponent, Vice President Hubert Humphrey, come from behind and defeat Nixon. In a tape-recorded conversation on June 17, 1971, Haldeman suggests that Nixon retrieve a file from the Brookings Institution, a center-left think tank, that supposedly showed how Johnson played politics with national security.

“You could blackmail Johnson on this stuff, and it might be worth doing,” Haldeman says. It’s not clear exactly what Haldeman has in mind, but Nixon perks up. He suddenly remembers that he signed off on a proposal by White House aide Tom Charles Huston to use wiretaps and break-ins to protect national security. “Bob, you remember Huston’s plan? Implement it,” Nixon says. A staffer objects, and Nixon explodes, “I mean, I want it implemented on a thievery basis. Goddamn it, get in there and get those files. Blow the safe and get it.”

The Brookings break-in never happened. Nixon’s aides usually (but not always) knew enough to ignore or sidetrack presidential effusions. Nonetheless, Nixon’s desire to have a team of break-in artists led to other, later escapades by the so-called White House Plumbers, including the September 1971 break-in at the office of the psychiatrist of Pentagon Papers leaker Daniel Ellsberg, and the June 1972 break-in at the Watergate offices of the Democratic National Committee.

In Chasing Shadows, Hughes, a Nixon-tapes expert who has done valuable work for the University of Virginia’s Miller Center Presidential Recordings Program, explores why Nixon was so eager to break into Brookings and retrieve the file on Johnson’s bombing halt. Yes, it might be used to embarrass or “blackmail” LBJ, as Haldeman suggested. But Nixon may also have feared his own exposure. In the lead-up to the election, Johnson had offered peace negotiations in exchange for the halt in bombing. For years, historians have tried to get to the bottom of allegations that Nixon, using a pro-Nationalist Chinese lobbyist named Anna Chennault as a go-between, tried to get the South Vietnamese government to torpedo the proposal. The evidence remains a little sketchy. In a recently released oral history, Huston, who looked into the bombing halt at Haldeman’s request, suggests Nixon was culpable, but there is still no smoking gun. Nonetheless, Hughes shows that we still have much to learn by connecting the dots of Nixon’s angry venting and the shadowy world of national-security spying.

Hughes’s fellow Nixonologist Luke Nichter, who is a professor at Texas A&M and runs an excellent website called nixontapes.org in addition to co-authoring The Nixon Tapes, is already following this trail. He recently told me that he is looking for evidence of other Nixon-era break-ins conducted in the name of national security. This sort of deep-cover spying hardly started with the cybersleuthing disclosed by Edward Snowden. Since the early days of the Cold War, a vast national-security apparat has waxed and waned and waxed again. Nixon had the misfortune to get caught, partly because he was consumed by his desire to get even with his enemies.

There will be more books growing out of the Nixon tapes. John Dean, the Nixon White House lawyer and whistleblower, has his own version, The Nixon Defense, out in August. Transcribing the Nixon tapes is “more art than science,” Nichter says—the quality is poor, inflections get lost or blurred. But the tapes remain a trove of undiscovered secrets.

(Image via National Archives and Records Administration/Wikimedia Commons)