Jeffrey Martin

Mapping Better Decisions At EPA

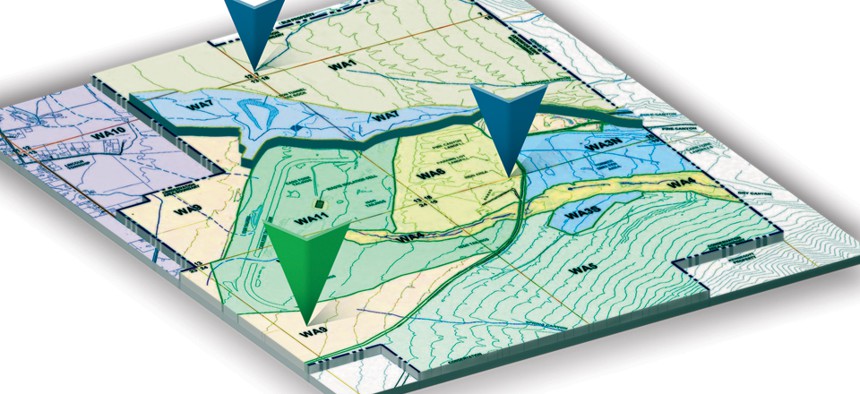

Customizing geographic data helps the agency target pollution problems.

The Environmental Protection Agency office charged with taking legal actions against water and air polluters used to organize its enforcement targeting meetings around spreadsheets and graphs.

Those spreadsheets detailed places with large oil and gas production and other possible pollutants where EPA might want to focus its own inspection efforts or reach out to state-level enforcement agencies.

During the past two years, the agency has largely replaced the spreadsheets and tables with digital maps, which make it easier to visualize precisely where the top polluting areas are and how those areas correspond to population centers, according to Harvey Simon, EPA’s geospatial information officer. This allows the agency to focus inspections and enforcement efforts where they will do the most good.

“Rather than verbally going through tables and spreadsheets you have a lot of people who are not [geographic information systems] practitioners who are able to share map information,” Simon says. “That’s allowed them to take a more targeted and data-driven approach to deciding what to

do where.”

The change is a result of the EPA Geoplatform, a tool built with Esri’s ArcGIS Online. The product allows agencies to build custom Web maps using base maps provided by Esri mashed up with their own data.

When the EPA Geoplatform launched in May 2012 about 250 people were registered to create and share mapping data within the agency. That number has grown to more than 1,000 during the past 20 months, Simon says.

“The whole idea of the platform effort is to democratize the use of geospatial information within the agency,” he says. “It’s relatively simple now to make a Web map and mash up data that’s useful for your work, so many users are creating Web maps themselves without any support from a consultant or from a GIS expert in their office.”

A governmentwide geoplatform was launched in 2012, spurred largely by agencies’ frustrations with the difficulty of sharing mapping data after the 2010 explosion of the Deepwater Horizon oil rig in the Gulf of Mexico.

The platform’s goal was twofold. First, officials wanted to share mapping data more widely between agencies so they could avoid duplicating each other’s work and to share data more easily during an emergency. Second, the government wanted to simplify the process for viewing and creating Web maps, so they could be used more easily by nonspecialists.

EPA’s geoplatform has essentially the same goals. The majority of the maps the agency builds using the platform aren’t publicly accessible, so EPA doesn’t have to worry about scrubbing maps of data that could reveal personal information about citizens or proprietary data about companies. EPA publishes some maps that don’t pose privacy concerns on its websites as well as on the national geoplatform and Data.gov, the government’s data repository.

When ArcGIS Online has been judged compliant with the Federal Information Security Management Act, or FISMA, EPA will be able to share significantly more nonpublic maps through the national geoplatform and tap into more maps produced by other agencies, Simon says. The Agriculture Department is in charge of that certification process, which was not complete as of press time. Based on where it stands in the FISMA process, Esri expects it to be complete soon, the company told Nextgov.

EPA’s geoplatform has also made it easier for the agency’s environmental justice office to share common data.

EPA’s environmental justice field offices, which provide grants and guidance to communities overburdened by pollution, had developed numerous desktop-based mapping tools, each of which used environmental and census data in slightly different ways, Simon says. Now the agency is standardizing those tools so field offices can share information consistently using the geoplatform.

EPA hopes to publish more public maps that will be useful to entrepreneurs and nonprofits looking at issues such as how highway developments and traffic patterns affect the environment, Simon says.

The agency would also like to integrate more maps across its public Web presence to give citizens a more

visual understanding of environmental issues and to integrate more real-time data into public Web maps. As the government’s ability to synthesize real-time data improves, for example, the agency might publish maps that show sensor data during environmental emergencies.

“Instead of taking weeks to process that data and figure out how to display it, we could potentially use it for operations immediately and prep it for public consumption as well,” Simon says.

EPA might also cull data from Twitter, he says, to map how the public is reacting to some regional environmental concern such as odor coming from a river or other body of water.

NEXT STORY: The Pivot To Asia Hits Rough Waters