sponsor content What's this?

Contact Tracing Programs Survey Findings and Recommendations

Neustar has been working with state and local health and human service (HHS) departments to connect tracers with contacts faster and more efficiently. In support of this collaboration, Neustar conducted a multi-state survey to learn more about the challenges unique to contact tracing programs’ outbound communications. Read this blog to learn about five major challenges that contact tracers face in their outreach efforts, and how to mitigate them.

Presented by

Neustar

Human-driven phone-based contact tracing is the backbone of states’ contact tracing programs. Success of these programs depends on reaching infected cases—and their recent close contacts—as quickly as possible to support them in self-isolating or seeking care. However, hurdles to reaching and alerting the right parties, similar to those that other types of outbound communications organizations face, stand in the way.

Since 1999, Neustar has been helping outbound communications organizations to reach the right person at the right number and right time. Through our unique relationships with phone carriers, management of over 90 percent of U.S. caller ID, and our industry leading Neustar OneID® identity management system, we address critical aspects of outbound communications.

Neustar has been working with state and local health and human service (HHS) departments to connect tracers with contacts faster and more efficiently. In support of this collaboration, Neustar conducted a survey* to learn more about the challenges unique to contact tracing programs’ outbound communications.

Challenges facing contact tracing programs

The survey revealed five major challenges that contact tracers face in their outreach efforts: time needed to engage with cases and their contacts, tracers’ job experience, availability of contacts’ information, efficiency of tracers’ outreach, and ability to generate a list of cases’ recent contacts. Mitigating these challenges is critical to making tracing programs more efficient and effective.

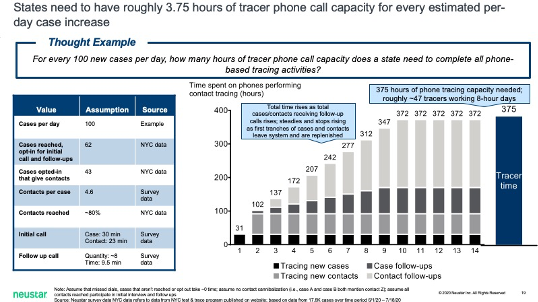

Each COVID-positive case takes nearly 100 minutes of tracers’ time

The time survey respondents spend with each contact falls into one of three categories: the initial call (23 minutes for contacts, 30 minutes for cases), follow-up calls (72 minutes for cases and contacts), and missed dials. (This is more effort than was estimated by the Contact Tracing Workforce Estimator in May.) For every 100 new cases, a contact tracing program needs approximately 375 hours of tracer phone call capacity—roughly 47 tracers working an eight-hour day—to reach and follow up with each new case and their average 4.6 contacts.

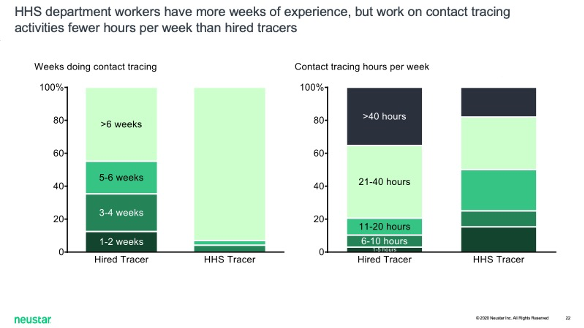

Less than half of hired tracers have more than seven weeks of experience

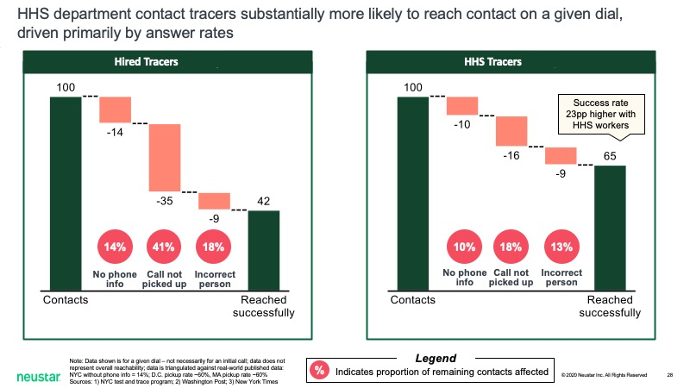

In many states, HHS departments need extra help to achieve adequate coverage for contact tracing. Roughly 11,000 tracers were working in May. That number had grown to at least 41,000 by late July, far less than what may be needed. Hired tracers, roughly half of whom had been in their roles for six weeks or less, reported spending 30% less time than staff tracers on an average call with a case or contact, and were less successful at reaching a given contact in a given call (51 percent of hired tracers versus 70 percent of staff tracers). However, hired tracers spent more hours on contact tracing activities per week than staff tracers.

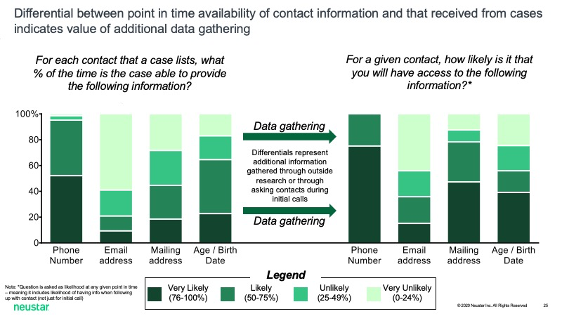

Contact information is difficult to gather

Tracers may receive incomplete, inaccurate, or no data about contacts. Cases often do not know the phone numbers or addresses of their contacts, or they may refuse to provide this information. Most tracers said they were likely to acquire a contact’s phone number when they requested it from a case (i.e., they expected to be successful more than 50% of the time). 42 percent felt the same about acquiring a contact’s physical address. Confidence fell to 20 percent for acquiring a contact’s email address. Outside research or asking contacts during initial calls was generally perceived as effective for acquiring additional phone numbers and physical addresses, though not for contacts’ email addresses.

40 percent of all calls fail to reach the intended recipient

Tracers blamed most call failures, aside from recipients not answering, on the numbers called being out of service (52 percent of respondents) or on the number called belonging to someone other than the intended contact (41 percent). Staff tracers were 23 percent more likely than hired tracers to reach contacts on a given dial because contacts were more likely to answer their calls.

Cases can’t, or won’t, name possible contacts

On average, each case provides four to five contacts. Staff tracers reported eliciting an average 5.8 contacts, while hired tracers reported eliciting an average 3.5 contacts.

Each of the above challenges hampers the efficiency and effectiveness of contact tracing programs. Higher average time spent communicating with each case increases the number of tracers needed to manage a state’s overall case load. Less-experienced tracers will need precious time to match the performance of their more-experienced peers. Tracing efforts will be stymied by incomplete, inaccurate, or altogether absent contact information. A meaningful amount of tracers’ calls will fail for lack of quality phone data. Cases will forget whom they’ve contacted in the days following their infections, or they will refuse to name their contacts. Given these challenges, it is critical that contact tracing organizations connect with confidence early with as many contacts as possible.

Read: Why Contact Tracing Fails and What to do About It

How to reach more contacts more efficiently

When contact tracing organizations have adequate time, support, information, and resources, they reach more infected contacts. Every measure taken today to increase the effectiveness of contact tracing will pay off in lives saved and economic disruption mitigated. At minimum, contact tracers need to reach 75% of potentially infected individuals within 24 hours in order to mitigate painful lockdown measures. Contact tracing programs would improve operations and results by leveraging the following alternative contact methods.

Use text messaging and email more

Survey respondents reported spending roughly 70 minutes on follow-up (70 percent of the total tracing time) per case or contact. If some of those follow-ups could be conducted via email or text message (i.e., personalizing and sending template messages), it would take tracers less time. This might allow them to manage a larger load of cases and contacts. Approximately 60 percent of tracers noted that emails were opened more than half of the time and contacts responded to more than half of text messages. (However, the average percentage of recipients who click a link in an email from a health-related sender vary between 2.7 percent and 6.9 percent. Even if this rate is higher for contact tracers’ emails, it seems to imply that texting is more effective.)

Nearly all tracing programs with relevant survey data send emails and text messages to cases or contacts. Knowledge about which phone lines are mobile and can receive SMS could increase tracing programs’ ability to text contacts. Verified consumer data, corroborated by multiple sources, would improve tracers’ ability to reach contacts at their primary email addresses.

Increase right-party contact (RPC) rates with better phone data

Every year, approximately 75 million people change their phone carriers and 45 million change their phone numbers. A recession sparked by COVID-19 may cause contacts’ phone information to change faster. Proactive contact tracing programs must implement strategies that make certain that contacts’ information is complete and accurate prior to calling. A clean and robust contact record streamlines outbound communications processes and increases RPC rates. Organizations are better positioned to make contact sooner when they have contacts’ most current data pushed to their databases automatically.

Give contacts more reason to answer

Why might staff tracers be 23 percent more likely than hired tracers to reach a contact on a given dial? One explanation has to do with the caller’s phone number. A freshly provisioned phone number for a newly hired tracer might not have been optimized for display on a contact’s Smartphone or caller ID. If the hired tracer’s call displays as blank or “SPAM risk,” then the recipient is less likely to answer. Almost 90 percent of individuals say they are more likely to answer a call if they can be certain of who is calling.

At the time of this writing, many states’ new case numbers are rising faster than their contact tracing programs can handle. Some form of targeted lockdowns may be required to reverse this trend. Nevertheless, when the “curve” has been bent back down, contact tracing programs will play an integral role in enabling a more nuanced, less painful response to the pandemic. The more efficiently tracing programs can reach contacts—via email or text, with better phone data, and by optimizing how their caller ID displays—the sooner that can happen.

*Survey methodology

From June 30 to July 16, Neustar surveyed (via phone interview) 72 state and local health and human services (HHS) department workers (“staff tracers”) and (via online survey) 136 hired contact tracers (“hired tracers”) from 39 states. The same survey was administered to all tracers. Respondents answered as many as 40 questions about their careers, how successful their calls with cases and contacts were, data-collection methods, and day-to-day operations. While the survey was relatively small, its span across dozens of states’ tracing programs affords a novel glimpse into the state of the country’s tracing effort.

This content is made possible by our sponsor Neustar; it is not written by and does not necessarily reflect the views of Government Executive's editorial staff.

NEXT STORY: Inclusive care: The road to empowering and supporting military and Veteran caregivers