CDC’s Leisha Nolen packed a travel kit of lab supplies for her trip to Sierra Leone. CDC

Around Government

Disease detectives, designing dog noses, aligning employees’ mood with the mission.

The Disease Detectives

CDC’s intelligence officers were on the case even before the Ebola outbreak made headlines.

By Susan Fourney

Imagine having a job and not knowing where your next commute will take you or what will be expected of you when you get there, and if the work doesn’t get done right, people could lose their lives. No pressure.

In early November, Dr. Leisha Nolen was packing her bags for Sierra Leone, the epicenter of the largest Ebola outbreak in history. Nearly 5,000 people had died by then, and the work of containing the disease promised to stretch weeks, if not months, into the future.

Nolen, an epidemic intelligence officer at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, tracks myriad public health mysteries. She has traveled to places like the Democratic Republic of Congo to hunt down monkey pox and Micronesia to investigate melioidosis. She made two trips to West Africa in recent weeks.

“You get there and do what’s needed. You never know what that will be. When I arrived I ended up doing a lot of policy work,” says Nolen, who helped the local ministry develop a universal plan for addressing the outbreak. Other assignments include data collection, lab work and training local health officials in contact tracing. “You’re literally working every day from 6 a.m. to 11 p.m.,” she adds.

As the situation worsened last spring, CDC put out a call for volunteers from across the agency to travel to West Africa. A core team of six to eight has grown to as many as 180. The Ebola outbreak signals only the third time in the agency’s history that it has cranked its Emergency Operations Center up to the highest activation status—Level 1. The other two times were post-Hurricane Katrina and during the 2009 outbreak of the H1N1 flu virus.

“It’s a horrible, horrible situation. But this is one of those times when you know why you’re there,” Nolen says. “Even doing something little is having some impact, and that’s really satisfying.”

Gone to Pot And the Dogs

Dogs are known for precision sniffing, which is why security and law enforcement agencies use them to find bombs and drugs. It’s also why federal scientists tasked with improving explosives and narcotics detection at airports and other checkpoints started studying dog noses and then 3-D printing what the National Institute of Standards and Technology calls “the first anatomically correct dog nose that realistically sniffs.”

The devices, modeled after a female Labrador retriever, expel strong air jets away from the nostrils the way real dogs do when exhaling. This helps pull in new smelly air “from impressive distances,” says NIST scientist Matthew Staymates. The process repeats up to five times a second.

NIST’s dog nose research started as a side project to track the movement of vapor—potentially carrying explosives or narcotics. “We built an artificial dog nose that sniffed like a real dog and began flow visualization experiments in our schlieren optical system,” Staymates says, referring to a device that can visually render variation in air temperature and density.

The researchers will soon print their best dog nose yet with the Connex500 3-D printer the agency bought in August for $228,977. The machine can print multiple substances, such as the hard and soft parts of the model nose, into one object.

The artificial noses aren’t used at security checkpoints. “This is strictly a research tool,” Staymates says.

-Rebecca Carroll

Feel Well, Work Well?

Consultant helps agencies align employees’ mood with the mission.

Managers worried about disengaged staffers have a new remedy on offer. The General Services Administration has booked the Ken Blanchard Companies—founded by the author of The One Minute Manager —to deliver Employee Work Passion Assessments to any agencies feeling the need.

Unveiled in October to several dozen federal employees at Washington’s City Club, the new tool updates Blanchard’s long-standing situational leadership development system with onsite coaching and employee surveys designed to dovetail with President Obama’s management agenda.

The federal government loses 19,000 work years annually due to sick days, according to the company’s literature, which cites 35 years’ experience with corporations like Nissan, Johnson & Johnson and Nike as well federal customers ranging from the CIA to the Marines to the Food and Drug Administration. Workshop surveys measuring 12 engagement factors—among them “task variety”—have shown retention increasing 17 percent, turnover cut by 28 percent and productivity rising 10 percent, the sales team noted.

In a nutshell, improving engagement means awakening employees to what they can gain from autonomy, according to the Blanchard group. “Motivation is a skill that can be taught and nurtured. But the new F-word in business and government is ‘feelings,’ ” said motivational speaker and author Susan Fowler, adding that too many employees are feeling insecure.

Disengagement, added Bob Freytag, a senior partner at Blanchard, comes from “worry about being judged and seeming needy, which keeps people from asking leaders for what they need and discussing goals.” An optimally motivating workplace offers employees a “sense of well-being aligned with the mission,” which promotes above-average work, discretionary effort and good citizenship, he said.

Blanchard licenses cost $60 per person annually for federal agencies with fewer than 25,000 employees and $45 for those with more.

- Charles S. Clark

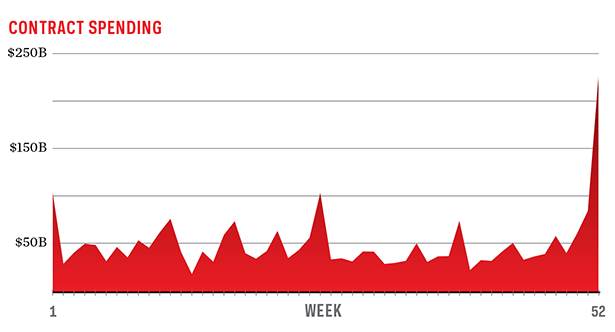

Money to Burn

Agencies on average spend 4.9 times more in the fiscal year’s final week than they do in a typical week, according to a report examining 14.6 million federal contracts from 2004 to 2009. The last-minute spending surge was more modest at the Justice Department, which has special authority to roll over up to 4 percent of budget for information technology projects. The authors suggest allowing some rollover of excess funds into the next budget year would allow agencies to spend more wisely.

Source: National Bureau of Economic Research

NEXT STORY: Measuring Up