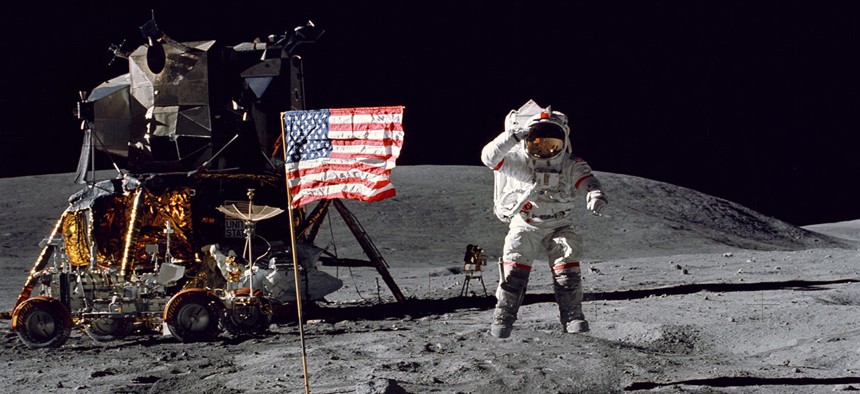

On April 16, 1972, the sixth manned lunar landing mission, Apollo 16, launched from Kennedy Space Center, Fla. on its way to conduct scientific investigations on the Moon’s Descartes highlands. NASA file photo

Why Donald Trump Wants to Go Back to the Moon

Trump wants to go back. Elon Musk's SpaceX and Jeff Bezos' Blue Origin could make it happen.

Today Donald Trump signed Space Policy Directive 1, an order to send humans back to the moon and beyond. A draft copy of the order seen by Quartz declares that “the United States will lead the return of humans to the Moon for long-term exploration and utilization, followed by human missions to Mars and other destinations.”

It’s a bold promise, timed to the 45th anniversary of Apollo 17, the final human mission to the moon. It’s also a promise that has been made by three previous presidents, each of whom was defeated by the political and financial challenges of deep space exploration.

Trump isn’t having an easy time so far: His nominee to run NASA, Jim Bridenstine, faces opposition from lawmakers. And real questions about the US return to the moon will be answered when NASA’s next budget is written, not today. The U.S. space agency has not designed a moon landing vehicle or other infrastructure for taking astronauts to the moon, and it will struggle to perform a moon landing during Trump’s term in office. (NASA’s current deep space exploration plan includes a new heavy rocket called the Space Launch System and a space capsule, called Orion, which will fly astronauts around the moon in 2019; it is also considering building a new space station in lunar orbit as a kind of stepping-stone.)

One advantage Trump has over his predecessors is an array of private companies investing in space exploration beyond low-earth orbit. NASA is already working with closely with lunar exploration companies like Moon Express, which received regulatory permission for a moon mission last year, and Astrobotic, a Carnegie Mellon spin-off that says it has a $1 billion manifest (pdf) to deliver to the lunar surface.

“A permanent presence on the moon and American boots on the surface Mars are not impossible,” Gwynne Shotwell, SpaceX’s president, said in October; the company’s founder, Elon Musk, has said his next rocketwill be designed around visiting the moon as well as his beloved Mars. “It’s time for America to return to the Moon—this time to stay,” Blue Origin executive Brett Alexander said in September, describing a lunar lander being developed by Jeff Bezos’ space company and promising additional investment if NASA was willing to partner with the firm. Meanwhile, Boeing’s CEO has promised the first astronauts to visit Mars will get there on one of his company’s rockets.

But why are so many interested in getting back to the moon, anyway?

Water and money

One irony about the Apollo astronauts is that they missed what newer robotic explorers didn’t: There is likely water, and perhaps quite a bit of it, on the moon.

The presence of water could make new activities: Cheaper long-term space habitation, thanks to the ability to grow food and create oxygen from water; and cheaper rocket propellant, if engineers can produce hydrogen and oxygen in space rather than bringing it up from earth. This could in turn bring futuristic business plans, like space tourism, asteroid mining, and orbital manufacturing, within reach of entrepreneurs. And, there may be other useful chemicals to be extracted from the moon, like Helium-3. George Sowers, who leads the space resources program at Colorado School of Mines, compares water on the moon to oil in the Persian Gulf, suggesting that there will be soon be an international scramble for claims on the moon.

Geopolitical tensions

Which brings us to a second motivator: China’s ambitious space program has announced that it wants to land humans on the moon by 2036. The European Space Agency has long argued in favor of a lunar village exploration concept. The US government doesn’t want to find itself left out a return to the moon, especially because American companies are likely to be among the first to stretch the current legal framework for space to its breaking point.

International space treaties, written in the early days of space exploration, leave much to interpretation and don’t account for commerce in space. Facts on the ground—or the lunar regolith—will matter in future debates over how people cooperate in space. US military is already talking up its new approach to space as a warfighting environment. Certainly, space entrepreneurs aren’t hesitant to invoke the international conflict. Robert Bigelow, who wants to build hotels on the moon, shared this slideshow during a recent conference to encourage the US to take action:

(Bigelow Aerospace)

Exploration and science

There are plenty of people in the space policy world who think that humans should set their sights directly on Mars and not waste time with a return to the moon. Yet lunar missions could enable, rather than hinder, more ambitious journeys into space.

Returning to the moon could help researchers understanding the health challenges faced by people who spend a long time in space. If ideas about water on the moon prove true, manufacturing propellant there could enable cheaper missions to Mars. Building out scientific infrastructure on the moon could create new opportunities for astronomers to get a clearer picture of the universe and planetary scientists to learn about the history of the earth. There’s still much to learn about the earth’s most important satellite.