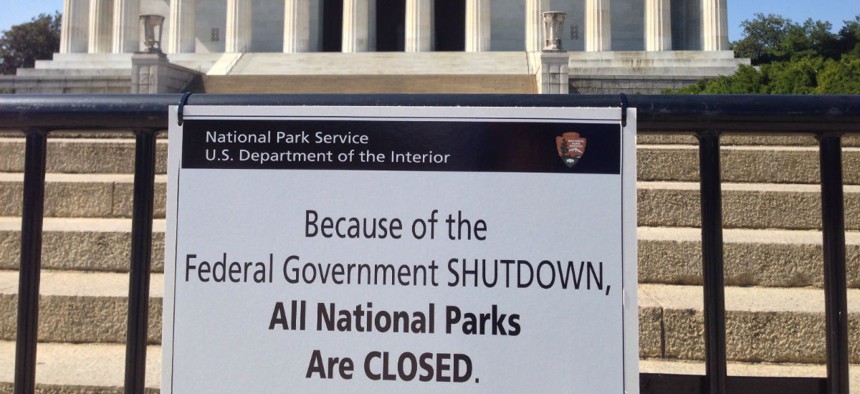

Flickr user John Sonderman

Shutdowns Affect Feds More Acutely Than Debt Ceiling Woes

But a government default could disrupt the payment of veterans’ benefits and military salaries, among other things.

Deadlines again loom for keeping the government open and dealing with the debt limit. So, which is worse for federal employees: A government shutdown or a debt ceiling crisis?

That depends on whether you are looking at short-term, or long-term consequences. Federal workers likely would feel the effects of a government shutdown more acutely than they would the repercussions of exceeding the debt limit. But if the government's alternative financing options are exhausted and the Treasury Department runs low on cash before a new debt limit is agreed upon, there could be problems.

“Failing to raise the debt ceiling would not bring the government to a screeching halt the way that not passing appropriations bills would,” said a 1995 report from the Congressional Budget Office. “Employees would not be sent home, and checks would continue to be issued. If the Treasury was low on cash, however, there could be delays in honoring checks and disruptions in the normal flow of government services.”

This differs from a government shutdown, which occurs when there is a lapse in appropriations, causing a funding gap. In that situation, as we all know, certain government operations cease until funding is restored, and by law employees deemed “nonessential” cannot work. Employees who are furloughed during a shutdown are not guaranteed retroactive pay, though in previous instances, Congress has provided it to them.

But a default would have serious economic consequences and affect the federal government's ability to borrow in the future. We know what happens when the government shuts down, but we’ve never experienced a default.

The Treasury Department on Thursday moved the deadline to raise the debt ceiling up two days to Nov. 3. “At that point, we expect Treasury would be left with less than $30 billion to meet all of the nation’s commitments—an amount far short of net expenditures on certain days, which can be as high as $60 billion,” said Treasury Secretary Jack Lew in an Oct. 15 letter to Congress. “The government makes approximately 80 million payments a month, including Social Security and veteran benefits, military salaries, Medicare reimbursements, and many others,” Lew continued. “In the absence of congressional action, Treasury would be unable to satisfy all of these obligations for the first time in the history of the United States.”

That means Congress must agree to lift or suspend again the $18.1 trillion debt limit by that date, or the government will start defaulting on some of its payments. Congress suspended the debt ceiling, a cap on how much the federal government can borrow, in February 2014. That suspension expired in March, but Treasury has used “extraordinary measures” to give itself more wiggle room to pay its bills.

One of those measures involves tapping the Thrift Savings Plan’s government securities (G) fund, the most stable offering in the TSP’s portfolio of retirement investments.

The Treasury secretary is authorized to temporarily suspend investment of amounts in the Civil Service Retirement and Disability Fund, and the G Fund. The G Fund is invested in interest-bearing Treasury securities -- bonds -- that comprise the public debt. The Civil Service Retirement Fund finances benefit payments under the Civil Service Retirement System and the basic retirement annuity of the Federal Employees' Retirement System, and those investments are made up of securities also considered part of the public debt.

Federal law (Sections 8348 and 8438 of U.S. Code Title 5) requires the Treasury secretary to refill the coffers of the G Fund and the CSRF once the issue of the debt ceiling is resolved, and to make up, in addition, for any interest lost on those investments during the suspension.

President Obama has said he will not negotiate over the debt ceiling this time around. Outgoing House Speaker John Boehner, R-Ohio, is reportedly planning to move on a clean debt limit increase before he retires from his post and Congress on Oct. 30.

As for a government shutdown, we managed to avoid one at the end of September, but the current continuing resolution keeping the government open expires on Dec. 11 and Obama has said he will not sign another stopgap spending bill. Furloughs during the holidays would be Dickensian, but they’re certainly a possibility.

(Image via Flickr user John Sonderman)

NEXT STORY: Looking for Expert Advice? TSP Has It.