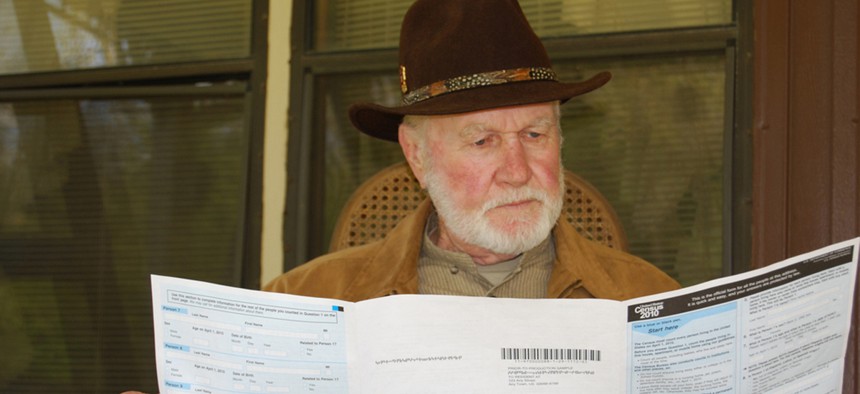

A farmer reads over the 2010 Census form. USDA file photo

Republicans Try to Rein In the Census Bureau

The GOP backs legislation that would make the American Community Survey effectively voluntary.

Why does the government want to know how many toilets you have in your home?

It might seem like a silly question, but it is now central to a dispute between congressional Republicans and the Obama administration over the kinds of questions that the Census Bureau can ask in its mandatory surveys.

In addition to the decennial census, the government’s head-counters every year send 3.5 million Americans a lengthy questionnaire seeking a wide range of information about their living situation and employment status. Known as the American Community Survey, it replaced the “long form” portion of the official census beginning a decade ago. In addition to questions about the number of toilets, since 2010 the ACS has also asked about what kind of plumbing people have in their homes, and about their Internet access, energy use, whether they receive food stamps, if live over a store, and how many cars they drive.

Republicans have long argued that such questions are too intrusive for a mandatory survey, and for the second year in a row, House-passed spending legislation would effectively make it voluntary by prohibiting the government from enforcing criminal penalties—which can reach $5,000—against people who refuse to participate in the ACS. To its opponents, the survey is yet another front in the privacy wars, and their arguments echo the complaints about government spying in the name of national security.

“This survey is another example of unnecessary and completely unwarranted government intrusion,” wrote Representative Ted Poe in a recent op-ed. “The federal government has no right to force Americans to divulge such private information, especially information that they are uncomfortable giving away.” Poe, a conservative former judge who represents the Houston suburbs, wrote the amendment that House Republicans included in the annual spending bill that covers the Census Bureau. While Democrats in the Senate successfully blocked it in previous years, the provision may stand a stronger chance now that Republicans run the upper chamber. President Obama has threatened to veto the legislation, in part because of the ACS amendment and deep cuts to funding for the 2020 Census.

Senator James Lankford, an Oklahoma Republican in his first term, said he’s concerned not only about the questions on the ACS but also with the methods the Census Bureau uses to make sure they get answered. Recipients are first mailed a survey that notes, in all capital letters on the envelope, that responses are mandatory. If they don’t send it back, government officials follow up with phone calls and house visits. Lankford told me that constituents have complained to him that after they told a census official they would not participate in the survey, the official sat in his car outside the house, waited for him to leave for work, and then returned to ask his wife to answer the questions. Poe has accused the government of similar “harassment” in Texas. “It’s just really odd,” Lankford said. “It comes across as just a really intrusive way to conduct a survey.” In response to the concerns, the Census Bureau is testing out a gentler approach without the bolded warnings, but according to Science, officials have said that when they have used less aggressive methods in the past, response rates dropped significantly.

A quick look at the Census Bureau’s website reveals an extensive effort to overcome skepticism, and resistance, to many of the questions on the American Community Survey. In addition to pamphlets outlining the history of the questionnaire, the website includes documents that explain why the survey asks each question, how long the question has been asked as part of the Census, and how federal, state, and local governments (as well as the private sector) use the information they gather. So why do they ask about toilets? “We ask questions about kitchen and plumbing facilities because federal and local governments need this information to allocate funding for housing subsidies and other programs that help American families afford decent, safe, and sanitary housing,” the Bureau says. Plumbing and kitchen questions first appeared on the Census “long form” in 1940. Without the toilet question, the government might not know that even in 2015, there are nearly 2 million Americans in rural communities without indoor plumbing, said Phil Sparks, co-director of The Census Project, a nonprofit advocacy consortium. “It’s irreplaceable,” Sparks said. “There is no option B for that data.”

The uses for ACS data go far beyond the government. More than a dozen business groups, including the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, wrote to lawmakers in April to urge them to keep participation in the survey mandatory. “There simply is no other source of high-quality, detailed socioeconomic information that is comparable across time and geography, allowing us to analyze current and trending markets and community needs and to plan future investments accordingly,” the organizations wrote.

We use the ACS data to make decisions on a daily basis concerning investment in new facilities, the availability of qualified workers and the need for job training programs, the characteristics (such as language preference, disability, veterans status and type of housing) of the communities we serve, and the need for new plants , stores and other places of business. Reliable information about population growth and density leads to the opening of new businesses in the best possible locations to serve the immediate needs of communities, helping create jobs.

Lankford said he understands the need for accurate data, but he’s dubious of the claim that there are no other options for the government. He said he’s asked the administration why it can’t get some of the data it seeks via the ACS from other sources, or at minimum to study the methods that private research firms use to conduct surveys. “Their approach seems to be the most expensive, most intrusive way to go about collecting data,” Lankford said. “If Gallup were to use these methods, they’d have lawsuits all over.”

A major part of the GOP concern with the American Community Survey is that, in its eyes, the ACS takes the government far beyond the rather straightforward directive embedded in Article I of the Constitution—that every 10 years, it should count all of the people for the purposes of determining proportional representation in Congress. The ACS, by contrast, is conducted annually. As Lankford put it: “This is not the every-10-years Census. This is a data update.” Yet Census officials and their allies like to quote James Madison in pointing out that the need for collecting additional information to formulate public policy is just as deeply-entrenched in the nation’s history. “These questions have been around since the beginning of the country,” Sparks said.

The Census Bureau also isn’t helped by its track record. The 2010 Census cost twice as much as the survey in 2000, a total that included $3 billion spent on new hand-held devices that didn’t work. This time around, the government is again promising to use new technologies that won’t require officials to physically walk every street in the country or use pencil-and-paper to count every one of its residents. But it needs money upfront to implement the new procedures, which the administration says will ultimately save $5 billion in 2020. So far, Republicans aren’t giving it to them. The House GOP proposal would eliminate any increase in funds for 2020 planning, and it cuts nearly $500 million in total from the administration’s request, including reductions for the American Community Survey.

Advocates are relying on Republicans in the Senate who they say have historically been more supportive of the Census, as well as on an administration that is battling GOP budget-cutters on a long list of presidential priorities. And while the 2020 Census is still five years away, Sparks said the current year is critical for planning. Without adequate funding, “the Census Bureau will have no choice but to revert to the old pencil-and-paper process that will cost billions more and won’t be as accurate.” That plea hasn’t yet moved Republicans.

NEXT STORY: Play of the Day: The GOP Field Visits Iowa