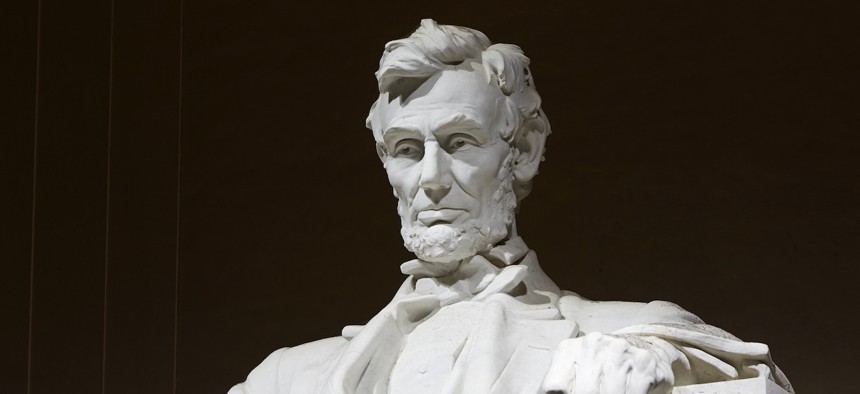

Allan Baxter/Getty Images

That Time Abraham Lincoln went to a war zone to escape office-seekers

The front lines of the Civil War were a vacation compared to being literally stalked in Washington.

The latest in an intermittent series looking back at groundbreaking, newsmaking, appalling and amusing events in government history.

In early April 1865, President Abraham Lincoln made a bold decision: He would travel to the front lines of the Civil War in Virginia to see for himself the Union Army’s effort to win the surrender of the Confederacy.

With victory near, the war-weary president wanted a close-up view of the conflict. To some of his advisers, that sounded like a terrible idea—especially when he proposed to tour the city of Richmond the day after it fell into Union hands. “Allow me respectfully to ask you to consider whether you ought to expose the nation to the consequences of any disaster to yourself in the pursuit of a treacherous and dangerous enemy like the rebel army,” Secretary of War Edwin Stanton wrote in a telegram to Lincoln.

The president was undeterred. “I will take care of myself,” he told Stanton.

In fact, Lincoln viewed the trip as a vacation, or at least a respite from a debilitating existence in Washington. In February 1865, Lincoln was “more depressed than I have seen him since he became president,” a visitor to the White House. At one point, the exhausted president had to hold a Cabinet meeting from his bed.

It wasn’t just being a wartime president that wore Lincoln down. The more immediate reason, writes Noah Andre Trudeau in Lincoln’s Greatest Journey, a chronicle of the last weeks of his life, was that “Lincoln’s reelection once more opened the floodgates for job seekers eager to be rewarded for their efforts on his behalf.” Lincoln tried in vain to convince his supporters that he would make very few changes in government positions, enlisting the aid of members of Congress in driving home the point.

“The Saturday evening before he left Washington to go to the front, just previous to the capture of Richmond, I was with him from seven o’clock till nearly twelve,” wrote Henry J. Raymond, founder of the Republican Party and The New York Times. “It had been one of his most trying days. The pressure of office-seekers was greater at this juncture than I ever knew it to be, and he was almost worn out.”

The pressure was personal. “As in 1861, Lincoln himself was not left unmolested,” wrote historians Harry J. Carman and Reinhard H. Luthin in 1943. “From the time of his reelection to the eve of his assassination, Washington was filled with seekers of federal jobs who literally lay in wait for him.”

When Lincoln took in an opera performance in March 1865, Trudeau writes, he explained that he wasn’t there for the music, but for a break. “I am being hounded to death by office seekers, who pursue me early and late, and it is simply to get two or three hours relief that I am here,” he told his companion for the evening.

At times, Lincoln was able to muster a sense of humor about the situation. “A fellow…once came to me to ask for an appointment as minister abroad,” he said at one point during his journey to the front. “Finding he could not get that, he came down to some more modest position. Finally, he asked to be made a [customs officer]. When he saw he could not get that, he asked me for an old pair of trousers.”

Advisers to Donald Trump’s campaign for a return to the presidency are licking their chops at the prospect of reinstating some version of a class of jobs known as Schedule F, which they could fill with thousands of loyalists, removing federal employees deemed insufficiently supportive of the president’s agenda. Indeed, James Sherk, a former special assistant to Trump and the architect of Schedule F, thinks the entire federal workforce should serve at the pleasure of the president.

That would do more than destroy the concept of an independent, professional, nonpartisan civil service that has served the nation well for more than a century. It would create an enormous headache for the Trump team—and potentially the president himself. It’s one thing to envision a workforce full of ardent supporters of the president, it’s another to sift through the hordes of would-be federal employees.

A return to the spoils system might seem very attractive to a president who makes no secret of disdaining federal employees and seeks to impose his will on the country. But it comes at a very high price. Trump advisers should think twice about the law of unintended consequences before they tear down the civil service system as we know it.