iStock.com/Javier_Art_Photgraphy

Biden Better Get Busy on Government Reform

Otherwise, federal breakdowns will start to accelerate.

Joe Biden took the oath of office on Jan. 20 with broken windows still visible on Capitol Hill, trust in the federal government to do the right thing at near-record lows, the presidential transition process running at subglacial speed, and the vaccine rollout already short on dollars and doses.

Yet, even with razor-thin margins in Congress, Biden headed toward his first anniversary in office with the most diverse group of presidential appointees in modern history, his $1.6 trillion American Rescue Plan still pumping billions into state and local governments, a $1.2 trillion infrastructure plan signed and ready to spend, and a $2 trillion spending bill working its way through dense legislative traffic.

Despite Biden’s legislative success, public support for a bigger government that provides more services barely moved above 45% during his first year in office, while support for a smaller government that provides fewer services inched up to a seven-point lead. Moreover, as if to show how quickly a government breakdown can stun a presidency, Biden’s FiveThirtyEight approval rating fell from 55% on April 14 when he promised to end the “forever war” in Afghanistan to 47% when the last U.S. evacuation flight left Kabul on Aug. 30. On Thanksgiving Day, it stood at just 43%.

Biden’s ratings may yet rebound if consumer confidence continues to rise after a summer drought, but the bureaucratic turbulence that set the stage for the summer’s breakdowns is certain to continue as the federal bureaucracy struggles with obsolete systems, bloated hierarchies, staffing shortages, cybersecurity gaps, planning breakdowns, a long list of programs on the edge of failure, a digital skills gap in the bureaucracy, and a growing brain drain as older executives retire.

Biden must also address the breakdowns that Trump left behind, most notably the 2019 border surge that continues today, recent increases in gun violence, violent crime, police misconduct, IRS and Postal Service delays, and the failed vaccine rollout that sparked the “pandemic of the unvaccinated.”

Most importantly for his future, Biden must reduce the risk of further breakdowns as he heads toward the 2022 and 2024 elections. The number of federal breakdowns has risen in every administration dating back to Reagan’s second term in 1984 but will not bend without significant government reform. Biden must act now or pay the penalty at the ballot box.

The president’s potential for success in this endeavor depends on the answers to six questions about government reform.

1. Do Americans still favor very major government reform?

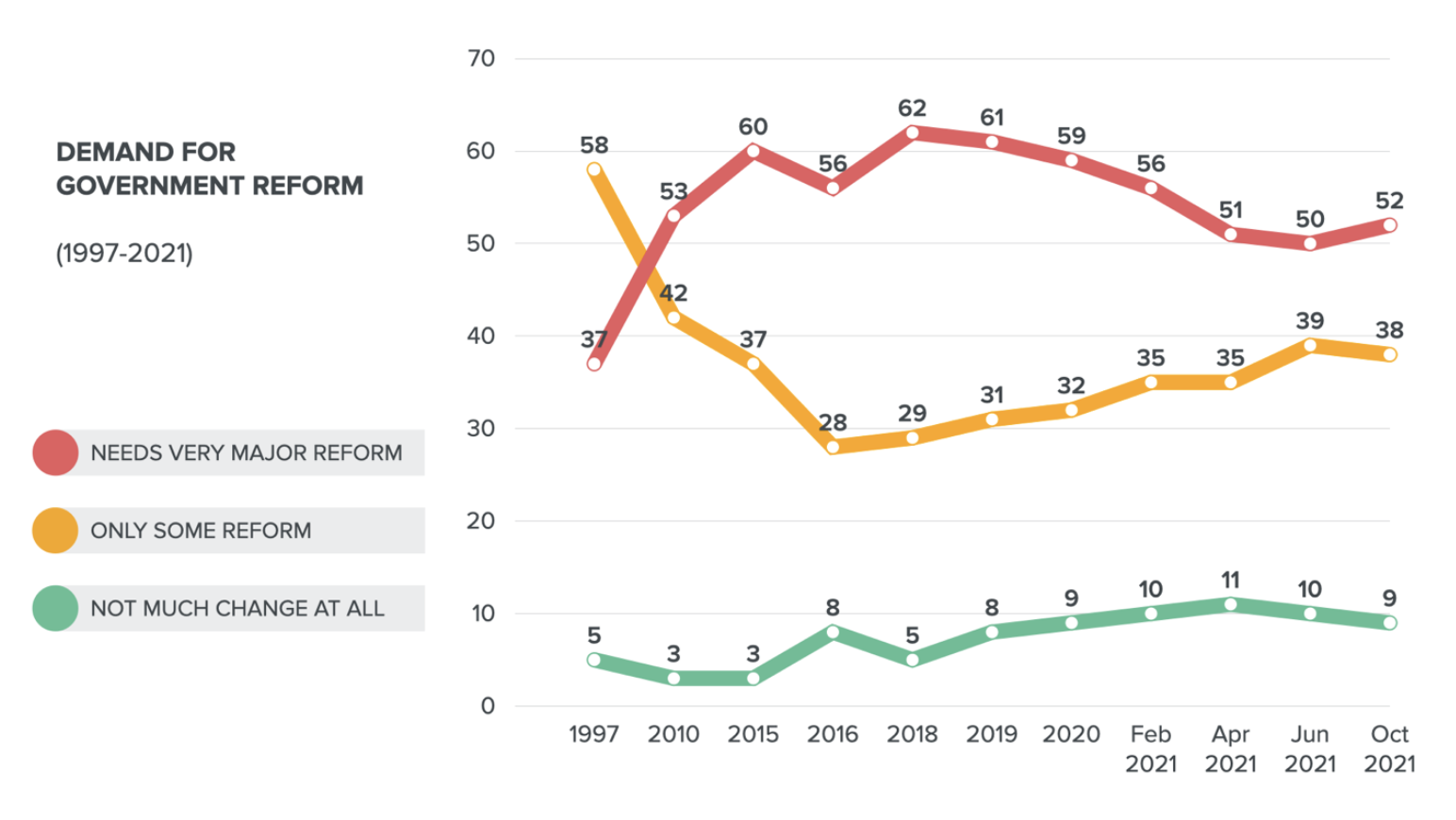

Despite a recent decline, public demand for “very major” government reform is still alive and well in American politics. Demand jumped during the Great Recession before falling slightly at the end of Obama’s presidency in 2016, then bouncing back up with Trump’s election. Despite small but steady drops in 2021, demand was inching up again by October.

The recent softening in demand appears to be related to economic growth, which Biden has described as “no accident, but a direct result of our efforts to deliver economic relief to families, small businesses, and communities across the country.” Even as he now works to stimulate new growth with his popular infrastructure plan, Biden would be wise to note the spikes in demand for reform during the Great Recession and the Russian election meddling scandal.

2. Do Americans still favor a bigger government that provides more services?

If Americans were deeply between smaller and bigger governme

nt before Biden’s election, they were ever further apart one year into his first term. The nation has been sharply divided in every survey since the Pew Research Center first asked its bigger/more versus smaller/fewer questions in the late 1990s. If there is any foreshadowing to be found in the most recent surveys, it is toward a smaller government that delivers fewer services.

These divisions are firmly linked to party identification, which makes unity particularly difficult. Interviewed last October, 65% of Democrats favored a bigger government that delivers more services, while 61% of Republicans favored a smaller government that delivers fewer services.

3. How big is the federal government’s blended workforce?

Presidents rarely miss an opportunity to celebrate the new jobs they create through federal contracts and grants, but seldom call a press conference to talk about the true size of the federal government’s blended workforce that the spending supports. A bigger government that delivers more services may be back in fashion at the White House, but the true size of government is largely hidden from review.

Most year-to-year changes in the number of active-duty military, civil service, and Postal Service employees are relatively small, but the number of contractors and grantees can rise by thousands during economic crises. Even as the jobs provide desperately needed help to hard-hit communities, they can spark stories about federal handouts and provoke presidential promises to shrink the workforce.

Biden could face a major test as federal contract and grant spending rises and 50,000 new federal jobs open up. Absent offsetting civil service retirements and unexpected departures, the blended workforce will climb past 12 million next year, a new record.

Even with more civil servants on the job, the federal government’s dependency on contractors and grantees for essential labor is certain to grow. As of 2020, there were already three contractors and grantees for every civil servant. The number is likely to surge with the Biden administration’s stimulus plans.

4. What kind of government reform will Americans support?

Americans can be divided into four reform philosophies based on what government should deliver and how much reform it needs:

- Expanders, who favor a combination of bigger government and only some reform

- Rebuilders, who favor a bigger government and very major reform

- Dismantlers, who prefer smaller government and very major reform

- Streamliners, who favor a smaller government and only some reform.

The philosophical equilibrium was relatively stable during the Clinton and Bush presidencies, but began to shift as the number of dismantlers grew during Trump’s 2016 campaign. Then it fell again in 2020, while the number of expanders grew during Biden’s campaign.

None of the philosophies has ever earned a majority in the past 25 years, but the expanders came close with a 43% share in 1997 before tumbling during Clinton’s second term. The dismantlers also earned a 43% share in 2016 as Trump surged to the presidency, then collapsed with scandal and impeachment.

Biden entered office with a liberal coalition of expanders and rebuilders that could be tested if new breakdowns highlight the unmet need for government reform.

The rebuilders and streamliners may yet provide the margin of victory in the 2022 and 2024 elections. Although both philosophies were largely missing from Biden’s expansionist agenda, both still lean Democratic. The rebuilders could also find common ground with the expanders if Biden puts government reform on his agenda. The rebuilders are 33% Democratic, after all, and favor a bigger government.

5. Do Americans still trust Biden to fix the government?

Biden drew near-majority public approval for running the federal government during his first six months in office, but was losing ground by early autumn. Between June and October, his excellent/good rating fell from 51% to 44%, while his fair/poor rating rose from 48% to 57%. The drop is almost certainly connected to the botched Afghanistan withdrawal and debt ceiling stalemate.

Even as Biden’s approval fell, the federal government’s rating inched up. Between June and October, the federal government’s excellent/good rating rose from 36% to 41, while the fair/poor rating fell from 64% to 58%.

Viewed through the lens of the four philosophies, Biden earned his highest job ratings from expanders, his lowest from dismantlers, and modest approval from the rebuilders and streamliners.

6. Can Biden stop the breakdowns?

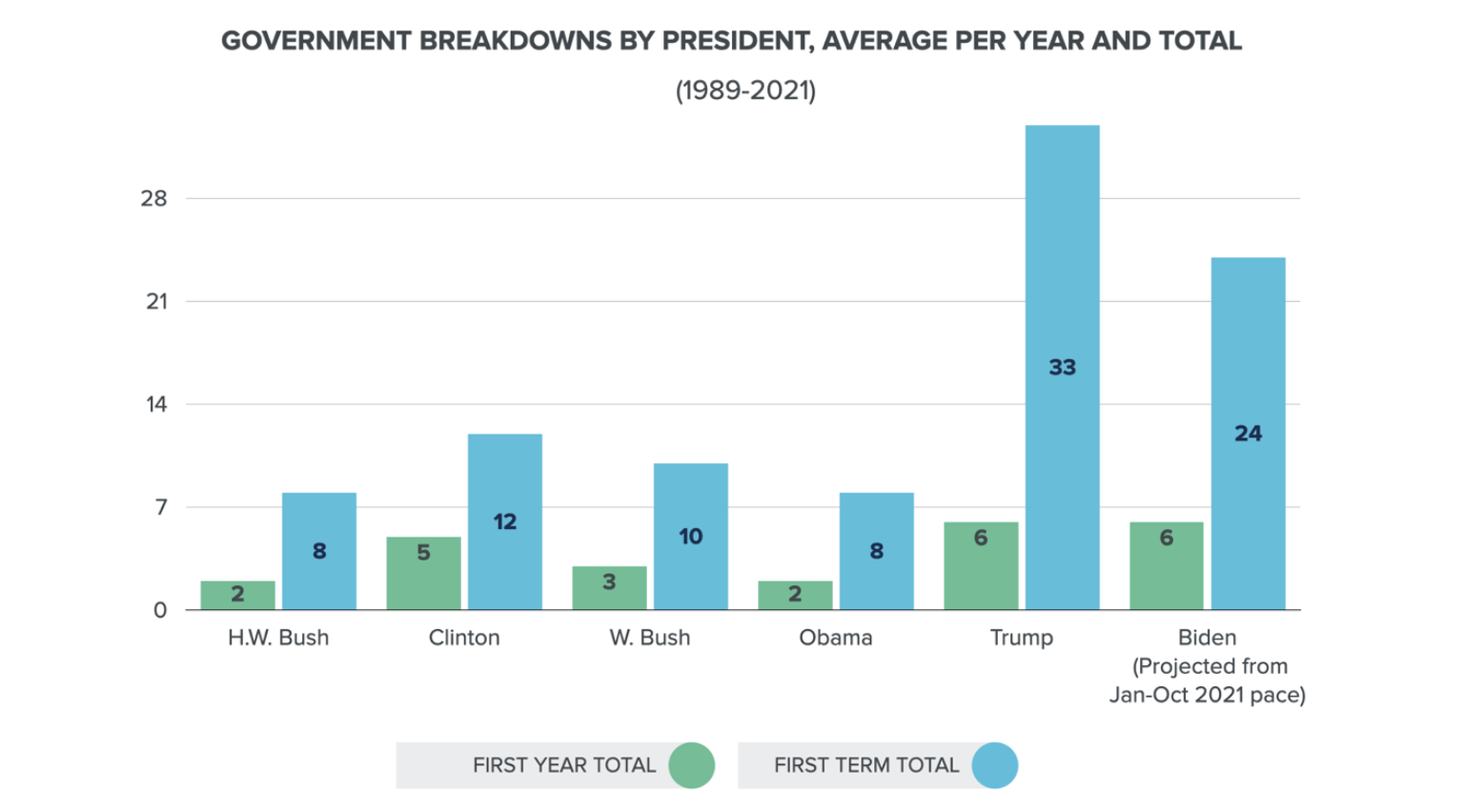

All presidents face government breakdowns on their watch, the only question being when the first will arrive, how long it will linger, and how many breakdowns will follow. George H.W. Bush’s first breakdown occurred in March 1989 when the Exxon Valdez ran aground in Alaska, Bill Clinton’s in January 1993 with the Waco standoff, George W. Bush’s in September 2001 with the 9/11 attacks, Barack Obama’s in January 2009 with a Postal Service financing crisis, Trump’s even before he was elected with Russian meddling in the presidential campaign, and Biden’s in January when Trump’s 2019 border surge returned.

Even with confused pandemic protocols issued by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the July eviction crisis, the chaotic Afghanistan withdrawal, and vaccine booster uncertainties, Biden’s breakdown list was well within the first-year totals dating back to the 1980s. However, if he continues at six breakdowns per year, he will end his first term with more breakdowns per year than George H.W. Bush (2), Clinton (3), George W. Bush (2.5), Obama (2), and inching ever closer to Trump’s 8 per-year record.

Trump’s breakdown pace increased sharply during the rest of his presidency. Biden must bend the breakdown curve back to a pre-Trump pace or put his reelection at risk. He already knows how much the Afghanistan breakdown cost. The question is not when another high-impact breakdown will hit, but how soon and what Biden will do in response.

Biden can reduce the odds of further breakdowns on his watch by returning public administration to the top of the president’s agenda. It has been 25 years since Al Gore’s reinventing government campaign, 40 since the Supreme Court voided the president’s reorganization authority, 50 since Jimmy Carter’s civil service and sunshine in government reforms, and 65 since Herbert Hoover gaveled the second national Commission on Organization of the Executive Branch to a close.

Biden took the first step toward deep-tissue government reform when he released the Biden-Harris Management Agenda just before Thanksgiving. Built around promises to empower the federal workforce, improve “customer experience,” and “catalyze outcomes that support building back better,” the jargon-laden agenda largely dodges the organizational problems that underpin many recent federal breakdowns.

Biden faces two challenges in reversing the recent breakdown curve:

First, he must fill the top jobs in government without delay. According to the Partnership for Public Service appointee tracker, just 189 of the Biden administration’s 802 top jobs had confirmed appointees by Thanksgiving, while another 231 had a nominee but were still waiting for Senate action. Another 165 had no nominee at all. If the past is prologue, many of Biden’s first appointees will be gone before the last of the empty positions have been filled. No one knows when the administration will finally nominate a director for the powerful Office of Management and Budget.

Biden need not fill every post to gain control of the government. On the contrary, he would be more successful over time if he flattened the bloated hierarchy that Trump left behind and ask his appointees to stay longer than the two-year average.

Second, Biden must forge a “build-back-better” management agenda that will strengthen federal performance into the future, while demanding congressional action and quick implementation. Compared to the long list of reforms that followed the New Deal and World War II, the inventory of recent reforms is meager at best and ineffective at worst. This agenda will not only help prevent future breakdowns but will give him protection when others arrive without warning.

Even limited reorganization authority would give Biden a chance to rebut continued public demand for reform. Until then, he'll have to work miracles with the tools he has.

NEXT STORY: Are Agencies Ready for the New HR?