Why Justice Is Investigating the Chicago Police Department

Given the department’s long history of police brutality, an audit is long overdue.

The U.S. Department of Justice is headed to Chicago to investigate whether police there have been regularly violating civilians’ civil rights. If a pattern is found—as was the case in the DOJ’s investigations into police departments in Ferguson, Cleveland, New Orleans, and a few other cities—Chicago police will be subjected to federal court-ordered reforms spelled out in a consent decree.

Already, Chicago’s history of police brutality looks rather like a pattern:

- Revelations of Chicago detectives applying a torture protocol to suspects in the 1980s to coerce confessions—which ultimately led to the city paying out more than $5 million in reparations to some of the victims of that torture.

- Discovery of a secret “black site” where police took suspects for aggressive (if not flat-out violent) interrogations of suspects before officially arresting them.

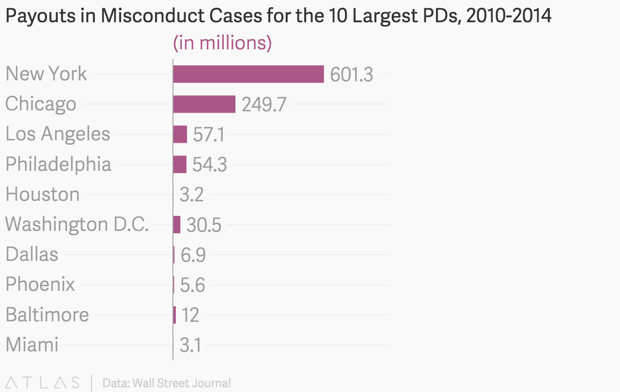

- Settlements from lawsuits over police brutality that have cost Chicago more than $521 million between 2004 and 2014—$84.6 million paid out in 2013 alone. The Los Angeles police department has paid $57.1 million in police brutality settlements between 2010 and 2014 by comparison, according to The Wall Street Journal.

Chicago recently paid $5.5 million to the family of Laquan McDonald, the 17-year-old African American teen who was shot 16 times last October by Chicago police officer Jason Van Dyke in what McDonald’s lawyers describe as an “execution.” The police dash-cam video of that killing was released right before Thanksgiving, over Mayor Rahm Emanuel’s controversial objections and decision to previously withhold it from the public.

Police are now preparing to release another police dash-cam video to the public, of an officer killing Ronald Johnson, 25, also black, in an incident that happened just a week before McDonald’s killing. That video is also finally being released over objections from the mayor and the police department. These videos, however, only show two of the most recent and most egregious cases of police brutality against a backdrop of thousands of civilian complaintsfiled against Chicago police—the grand bulk of which have gone undisciplined.

Emanuel ousted Garry McCarthy from his post as police superintendent last week, but many in Chicago and beyond have been asking for Emanuel to resigngiven the way he’s handled, or failed to handle, the violent culture of Chicago-style policing.

While the DOJ’s investigation has been welcomed by a number of police-reform advocates and law enforcement officials in the state, Emanuel initially said that such an audit would be “misguided.” He’s since changed his tune. Meanwhile, The Washington Post recently took a deep dive into relations between the DOJ and police departments under investigation over the past couple of decades and found that they’ve produced “mixed results.” Along withPBS Frontline, The Washington Post studied dozens of DOJ-triggered police reforms initiated since 1994, when Congress granted the department the power to investigate police departments in the wake of the Rodney King police beating. They found that:

The reforms have led to modernized policies, new equipment and better training, police chiefs, city leaders, activists and Justice officials agree.

But measured by incidents of use of force, one of Justice’s primary metrics, the outcomes are mixed. In five of the 10 police departments for which sufficient data was provided, use of force by officers increased during and after the agreements. In five others, it stayed the same or declined.

None of the departments completed reforms by the targeted dates, the review found. In most, the interventions have dragged years beyond original projections, driving up costs. In 13 of the police departments for which budget data was available, costs are expected to surpass $600 million, expenses largely passed on to local taxpayers.

Still, it’s hard to conceive how police departments have earned the public’s trust, especially in black neighborhoods where there have historically been problems, without DOJ oversight. As imperfect as the results have been over the short 20-year tenure of DOJ law enforcement investigations, it remains perhaps the only method through which the police themselves can be policed.

NEXT STORY: Agency Energy Use Reduced to 40-Year Low