A sign touting use of SNAP benefits at a farmers market sits at a farmers market in Florida in 2012. USDA file photo

Photo ID Cards Won't Stop Food Stamp Fraud

A new report finds that photo IDs cost more to implement than they save preventing fraud. And they make the program harder for beneficiaries to use.

Fraud is a real problem for the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program. Some places want to target SNAP fraud (or "trafficking" as it's called in the food-stamp policy sphere) through a controversial means. Legislators have proposed and in some states enacted laws that require SNAP beneficiaries to carry food-stamp cards with photo identification on them.

On paper, this might look like a tough-minded reform that aims to deter people from exploiting an important federal assistance program. But a new report from the Urban Institute finds that photo-ID benefits cards don't curb food-stamp fraud. This shouldn't come as any surprise.

SNAP fraud or trafficking happens when someone exchanges SNAP benefits for cash. There are a few different ways that fraudsters abuse SNAP. "Water-dumping" is when someone uses SNAP benefits to buy beverages, empties the bottles or cans, and then returns the beverage containers for cash. Some people sell benefits cards through social media: Craigslist, Facebook, Twitter. Sometimes people buy things using food stamps and turn around and sell them.

By far, the biggest form of SNAP fraud occurs with the participation of retailers who are authorized to accept SNAP benefits. In this scenario, trafficking occurs when a retailer gives a customer cash back on a SNAP transaction—for a high surcharge. Both retailer and beneficiary take cash on the transaction. In essence, they're using food-stamp EBT cards as federal ATM cards, with the beneficiaries taking out withdrawals and retailers taking out fees.

Consider that "runners" sometimes buy these EBT cards (and their associated PINs) from SNAP beneficiaries in order to traffick SNAP benefits on a broader scale with participating retailers. That's a full-scale racket. (Folks who are all caught up on Orange Is the New Black may remember that retail SNAP fraud plays an important part in one prisoner's backstory .)

So what can photo IDs on SNAP benefits cards do to prevent this kind of fraud? Nothing. Nothing at all, really. Retailers who are conspiring with beneficiaries to defraud the government aren't going to be deterred by an EBT photo card.

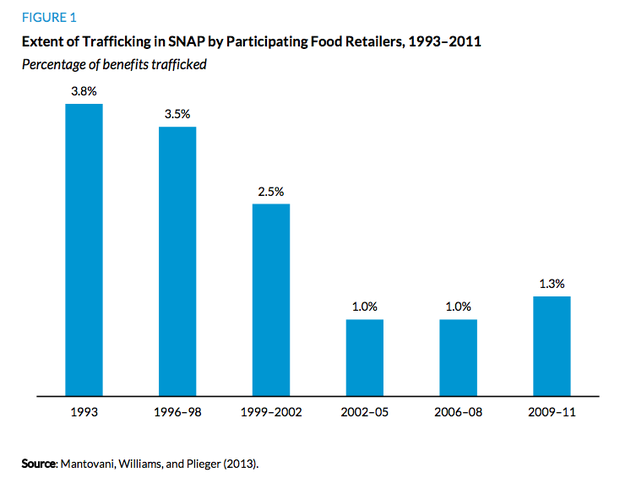

The Urban Institute report adds evidence to this thought exercise to show why photo ID cards are a misguided solution to SNAP fraud. First of all, food-stamp fraud is a narrow concern. Advances in recent years have curbed fraud significantly, most of all the adoption of PIN-enabled EBT cards for benefits (over paper coupons).

The actual amount of money lost to the federal government due to food-stamps fraud is not nothing, though. As the program has grown over the course of the Great Recession, the amount of money lost to fraud has increased, even as the share of benefits lost to fraud has fallen. "[W]ith the increased scale of the program, the annualized amount of diverted benefits has risen slightly over this period, from $811 million in 1993 to $858 million in 2009–11," the Urban Institute report reads.

The federal government tracks SNAP fraud mainly by monitoring electronic data from retailers. Too many even-numbered SNAP transactions (e.g., $50.00) conducted by one retailer can be one sign of fraud, for example. However, states have the right to go further in cracking down on fraud, including by adding photo identification to EBT cards—as Massachusetts and Maine have done, and as other states are considering.

Former Massachusetts Governor Mitt Romney rescinded in 2004 the state's first EBT photo-identification program, enacted as part of welfare reform in 1995. The Romney administration discovered that photo ID cards represented a burden on both the beneficiaries receiving them and the staffers creating them. Plus, retailers didn't necessarily check the ID cards on a routine basis, and anyway, the fraud takes place with the explicit participation of the retailer.

In fact, requiring photo IDs on SNAP benefits cards—as Massachusetts does, once again, as of 2013—undermines the program. Retailers are not supposed to treat SNAP transactions any differently than any other transaction; they would need by law to ask for ID for every card transaction in order to check identification specifically for SNAP transactions.

Further, SNAP is a means-tested benefit that flows through households, not individuals. The program is designed so that benefits can be used by adults living in the same household who are not necessarily direct relations. So a photo-identification card runs counter to the stated goal of the program, which is to provide food assistance to families and households.

The Urban Institute estimates the degree of fraud taking place in Massachusetts:

Based on [the U.S. Department of Agriculture Food and Nutrition Service's] most recent national estimate that transactions involving retailer trafficking amount to 1.3 percent of total annual SNAP redemptions, trafficking in Massachusetts amounts to an estimated $18 million annually (1.3 percent of $1.4 billion in annual SNAP benefits). Assuming that the SNAP participants involved in these transactions receive 50 to 70 cents on the dollar for their trafficked card balances, the diversion of benefits from these participants to retailers is $5 million to $9 million annually.

Read the full report from the Urban Institute to see what implementing photo identification costs Massachusetts versus what fraud costs Massachusetts. Spoiler alert: The cost of fraud prevention through photo ID requirements outweighs the savings gained by fraud prevention, because photo ID requirements don't prevent fraud!

Retailers are where the fraud is. After all, when a beneficiary takes cash in place of food benefits from SNAP benefits, that benefit is still going to the right person. It's still fraud—it's just not a "diversion" of benefits from beneficiary to retailer, as the Urban Institute notes. But when retailers take from the federal till, they're exploiting federal assistance at large as well as the beneficiaries in specific. That's the bigger problem.